In this article, Jennifer Johnstone presents an introduction to the Georgian Era, including a look at the class system and some very famous writers!

The Georgian era was a time of sumptuous architecture, literature, music, and style. It was the era that made the modern world we know today. The Georgians gave us many things, from some of our most famous writers such as Jane Austen and Mary Shelley to the industrial revolution. There was also the third Georgian King, King George, who lost American colonies, and went mad. And a class system we still see today in modern Britain.

Frontispiece to Mary Shelley, Frankenstein published by Colburn and Bentley, London 1831 Steel engraving in book.

Classification of the Georgian era

The Georgian era began with the German ‘House of Hanover’, or as they’re otherwise know ‘The Hanoverians’. The period lasted from approximately 1714 to 1830. There were three monarchs in the era, all Kings: George I, George II, and George III. The dynasty was accepted with the Act of Settlement (1701). Even though these kings were accepted as monarchs following the Act of Settlement, it is claimed by some that they were not particularly popular monarchs, especially George I. However, the aim of this article is not necessarily to decipher if the Georgian Kings were popular, rather, it’s main purpose is to show what the Georgians brought us. And one thing the Georgians did give us was some of the world’s best-known literature.

Literature of the Georgian era

The Georgian era brought us some great writers, such as Jane Austen, Percy Shelley, Mary Shelley, John Keats, and Lord Byron. Interestingly, it is the female writers, Mary Shelley and Jane Austen, who have stood the test of time, and are as much celebrated in today’s second Elizabethan era, as they were during the era they lived in, the Georgian era.

Today, Jane Austen is celebrated all over the world. There are numerous societies, celebrating the life and work of the woman who gave us stories such as Pride and Prejudice, Emma, Sense and Sensibility, and of course, Mansfield Park. An example of the celebration of Jane Austen comes from the ‘Jane Austen Centre’, a place that is hosting a summer ball and a Jane Austen festival in 2014. Another example of Austen’s relevance in the hearts of the British public is that she will appear on the ten-pound note from 2017. This could show that Jane Austen is as relevant today as she was in Georgian England. It can even be argued that with Austen being the face of the new ten-pound note, she is one of the most loved British authors of all time. After all, few other authors have been given a place on bank notes.

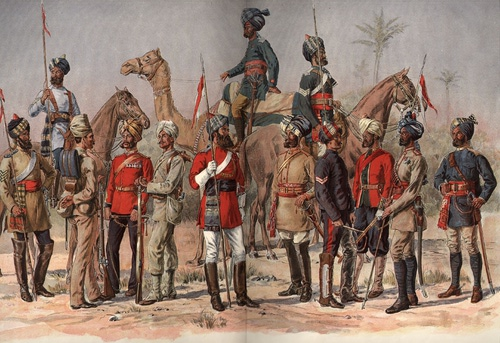

When we think of the Georgian era, we often think of Austen’s worlds and a grand upper class lifestyle. We rarely think of it as a gothic era, full of monsters, but this is what makes Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein a welcome breath of fresh air. Shelly gives us something completely different in her work.

Mary Shelley’s work of Frankenstein gives us a monster created under the eccentric scientist Victor Frankenstein. Frankenstein covers some of the same themes as Austen’s novels, including romance, and social class; however, there are also the themes of knowledge, alienation, guilt, and vegetarianism. Frankenstein forces us to think about the more negative aspects of society, and how societies can mistreat others. Perhaps, this was not surprising, as Shelley was the daughter of the feminist philosopher Mary Wollstonecraft. Wollstonecraft was a critic of the way women were treated in society, most famously noting this in her work The Vindication of Women’s Rights. Both Shelley and Austen spoke out against prejudice, and the patriarchal nature of society.

Industrial Revolution

The Georgians did not only give us great literature, they also gave us an industrial revolution and an agricultural revolution.

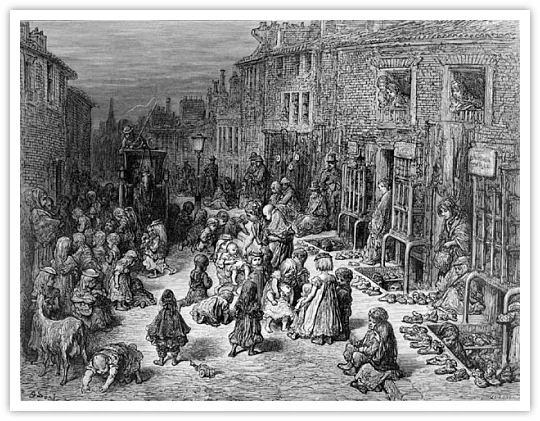

Before the industrial revolution, British industry was normally small scale and relatively unsophisticated. What this meant was that there were not the large factories or mass production that began in the Georgian era; rather, production was usually on a small scale. Meanwhile, the agricultural revolution changed the way that the farming world worked. A change in the way Georgians used tools during the industrial revolution, also saw a change in people’s living patterns and lifestyles. People began to live longer and moved to the cities.

Class structure

The Georgians shaped the nature of the social class system, and this remains in modern Britain. The upper class was a small segment of society and included the wealthiest. It was an elite aristocracy that was closed off to all others. The upper class was not infrequently subject to criminal acts in Georgian England though, as there was not a police force in the modern form. Secondly, there was the middle class. This class was a little broader than the upper class, but it still retained a small percentage of society. It was made up of various businessmen and professionals. And, last but not least, there was the working class. The working class made up the majority of the Georgian era’s population. It was a class that was exploited by the rich and it was often forced to work in the newly formed factories. Children, from as young as five, were even made to work.

Conclusion

The Georgian era attained an eloquent fashion, style, music, and literature, and is seen as a time that shaped the modern era that we live in today. It shaped the foundations of modern Britain, giving the country an industrial and agricultural revolution, along with a class structure that still exists in modern Britain. The Georgians also gave us some of our finest literature. Simply put, the Georgians gave us modernism.