The previous article of this series on the history of modern Greece concluded the discussion of the first 100 years after the beginning of the War of Independence in 1821. According to G. B. Dertilis we find ourselves at the end of the third period of bankruptcies and wars (1912-1922) – the first being 1821-1880 and the second 1880-1912. Two more will follow (1923-1945 and 1946-2012). (Dertilis, 2020, pp. 11-17) The proposed cyclability indicates specific features present in modern Greece that significantly hinder the escape from the vicious cycles described by Dertilis. (Dertilis, 2020, p. 29) Here I will discuss these features and describe how they affected the developments in Greece during the interwar period. Clientelism is proposed as the main source of Greece’s problems. But let’s start with one of its consequences, that will better suit us to present the major events of this period: namely, division and civil war.

I Division & civil war

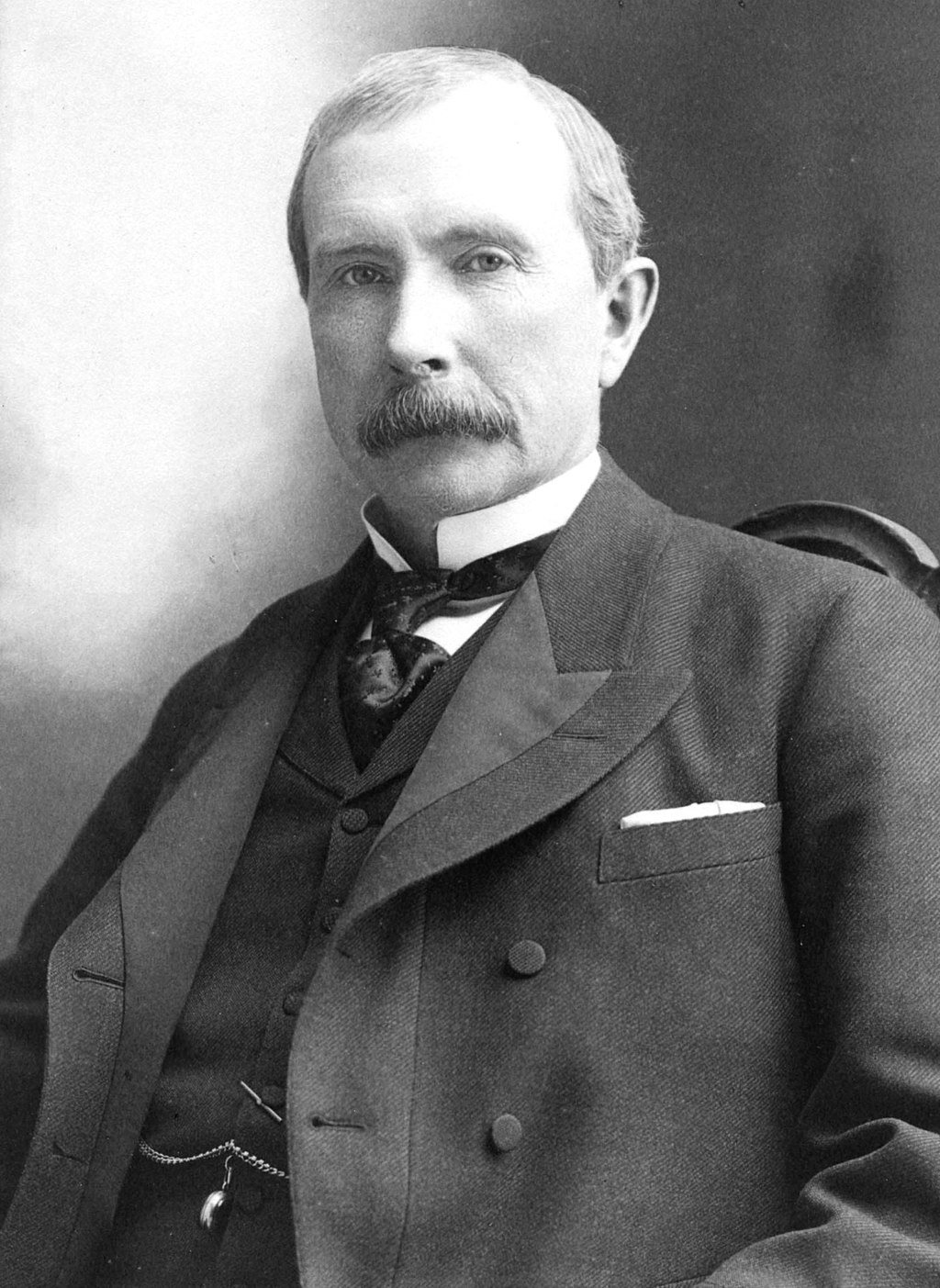

Division and civil war are present in modern Greek history already since the War of Independence. (Papageorgiou, History Is Now Magazine, 2021) The latest quarrel we examined that once more divided the Greeks was that between the prime minister Venizelos and king Constantine. (Papageorgiou, History is Now Magazine, 2022) The division to Venizelists and anti-Venizelists continued even after the king’s resignation, following the catastrophe of the Asia Minor Campaign in September 1922, and eventual death three months later in Palermo.

This period of modern Greek history starts with a gruesome event in November 1922, which is known as ‘the execution of the six’. These were leading figures of the anti-Venizelists including former prime minister Dimitrios Gounaris, that defeated Venizelos in the elections of 1920 preceding the disaster in Asia Minor. The execution took place under a military regime led by the Venizelist colonel Nikolaos Plastiras following a revolt of the defeated Army in September 1922. Despite international reactions calling for an annulment of the execution, Venizelos, at the time negotiating piece terms with Turkey in Lausanne as representative of the dictatorship in Greece (Mavrogordatos, 2019, p. 29), did very little to prevent it. (Dafnis, 1997, pp. 25-35)

The Treaty of Lausanne (Wikipedia, 2022) marked the end of the Great Idea aspirations for Greece (Papageorgiou, History Is Now Magazine, 2021) bringing the country to its current borders, more or less, as the Dodecanese would be the last territorial gain of modern Greece after the end of World War II. The loss of the territories in Asia Minor and especially Eastern Thrace caused the nagging even of some officers within the military regime like major general Theodoros Pangalos, who criticized Venizelos’ handling. (Dafnis, 1997, p. 65) In fact, it was not unusual for members of the Venizelist or anti-Venizelist space to change sides because of a political disagreement or pure interest.

It was this mixture of political disagreement on an electoral law that favoured the Venizelist candidates in the elections prepared by the regime for December 1923 (Mavrogordatos, 2019, pp. 33-34) and disappointment of officers feeling ignored by the Plastiras’ regime that led to a counter-revolt in October 1923. (Dafnis, 1997, p. 129) This was soon crushed by the Venizelists. The latter found the opportunity to purge the army from their rival officers (Mavrogordatos, 2019, p. 34) and as the palace identified itself with anti-Venizelism to rid themselves of the successor king George II. After the elections of December 1923, from which the anti-Venizelists abstained (Mavrogordatos, 2019, p. 35), the National Assembly declared the fall of the dynasty and the establishment of unreigned democracy on the 25 March 1924. (Mavrogordatos, 2019, p. 38)

This decision was further supported by a referendum held in April (70% for the unreigned democracy) (Dafnis, 1997, p. 262) but the anti-Venizelist leader Tsaldaris expressed his reservations for the new status quo. Thus, under the pretext of the protection of democracy, prime minister Papanastasiou passed a law aiming at the silencing of the anti-Venizelist propaganda with severe punishments imposed by military courts. (Mavrogordatos, 2019, p. 42) In his book, Mavrogordatos points out the similarity of the establishment of the unreigned democracy in Greece with that of the Weimar Republic in Germany as the result of the opportunistic partnership of the Liberals (Social – democrats in Germany) with the military. (Mavrogordatos, 2019, p. 39)

Indeed, the grip of the military on the Greek political life during this period is marked by 43 different interventions between 1916 and 1936. (Veremis, The Interventions of the Army in Greek Politics 1916-1936, 2018, pp. 291-299) Soon after the handover of the government to the politicians in December 1923, major general Pangalos came to power by force in June 1925 exploiting the reluctance of the government and of the leaders of the political parties to act decisively against him. In fact, he managed to obtain a vote of confidence from the parliament and to give this way a lawful mantle to his government. (Veremis, The Interventions of the Army in Greek Politics 1916-1936, 2018, p. 162) His turn towards the anti-Venizelists worried the democratic officers and following a series of blunders in domestic and foreign policy, including an invasion in Bulgaria on the occasion of a border incident involving the killing of three Greeks by the Bulgarians, he was finally removed from government and imprisoned in August 1926. (Mavrogordatos, 2019, pp. 45-47) He remained in prison till July 1928, when the Venizelists ordered his release. (Dafnis, 1997, p. 350)

The year 1928 marks the return of Eleftherios Venizelos himself to the premiership. Before that, Greece was under ‘’ecumenical government’’ following a public demand for, at last, collaboration between the parties, after the fall of Pangalos’ dictatorship (Mavrogordatos, 2019, p. 48) This did not last long though and, apart from some success in laying the groundwork for a sound economic policy (Dafnis, 1997, p. 395), it did not do much to cure the schism between the rival factions. Eventually, the Venizelists won a striking victory during the elections of August 1928: 226 out of 250 seats in the parliament. (Mavrogordatos, 2019, p. 54)

Venizelos’ new term was one of the longest in modern Greek history lasting for 52 months till November 1932. His government is credited with the approach to Italy, that, under Mussolini briefly occupied the island of Corfu in August 1923 (Dafnis, 1997, pp. 83-125), Yugoslavia and Turkey, the retainment of good relations with the Great Powers, and especially Great Britain, the settlement of the war reparations after World War I to the benefit of Greece, an extensive investment program in new infrastructure mostly in the new lands (that is territories added to Greece after 1912), a satisfactory financial situation with consecutive surpluses of the state budget, the strengthening of the rural credit with the creation of the Agricultural Bank, an educational reform focusing on the reinforcement of the productive occupations, the establishment of the Council of State to restrict government arbitrariness, and the continuation of the effort for the integration and assimilation of the refugees that flooded Greece after the Asia Minor catastrophe in 1922. (Dafnis, 1997, pp. 463-514)

One of Venizelos’ statements though, after his stunning victory in 1928, is characteristic of his intentions towards the opposition at that time. ‘The People of Greece made me a parliamentary dictator’, he said to his wife. (Mavrogordatos, 2019, p. 57) Thus, the most famous law of this time was that of summer 1929 ‘against the pursue of the implementation of ideas aiming at the overthrow of the social regime’. (Mavrogordatos, 2019, p. 58) It was introduced against the declared views of the Communist Party, although there was never a real communist threat during the interwar period (Dafnis, 1997, p. 505) (the Communists never received more than 5-6 % of the votes at the elections that took place between 1926 and 1936). (Mavrogordatos, 2019, p. 29) Nevertheless, it served, indiscriminately, the purpose of suppressing public protest during Venizelos’ term and later as well. (Mavrogordatos, 2019, p. 58)

The global economic crisis of 1929, that undermined Venizelos’ ambitious program, led to his call for the formation of an ecumenical government in March 1932, (Mavrogordatos, 2019, p. 59) but the failure, once more, of Venizelists and anti-Venizelists to reach a compromise rendered any such attempt short lived and a failure. Short lived was also Venizelos’ last government in January 1933 and he was finally defeated in the elections of March 1933. (Mavrogordatos, 2019, p. 64)

The military branch of the Venizelists did not take this development well. The former colonel Plastiras, leader of the army revolt in 1922 (see above), now a Lieutenant General, attempted to militarily cancel the passing of power to the anti-Venizelists. He failed and had to flee abroad in April to avoid the consequences. It is suggested that Venizelos did not act decisively to cancel Plastiras’ plans or that he even ordered the action. (Dafnis, 1997, pp. 620-622) Nevertheless, he was not prosecuted.

The fact that Venizelos was not prosecuted by the parliamentary and judicial authorities does not mean that he was spared from the vengeful fury of the anti-Venizelists. On the night of the 6th of June 1933, a cinematic attempt on his life took place, when he was returning to Athens from dinner at a friend’s house in Kifissia. Venizelos escaped, but during the manhunt involving the car carrying Venizelos and his wife, his bodyguards’ car, and the attackers’ car, one of his guards was killed, his driver was seriously wounded, and his wife suffered minor injuries. (Dafnis, 1997, pp. 636-640)

The acute confrontation between the two factions continued for twenty months after the assassination attempt. The sources of tensions included a systematic government: i) cover-up of the assassination attempt, ii) manipulation of the command of the army to end its control by Venizelist-democratic elements, iii) effort to change the electoral law to its benefit, iv) disregard of parliamentary procedures. (Mavrogordatos, 2019, p. 68) Eventually, in March 1935, Venizelos poured fuel on the flames backing an insurrection across northern Greece and the islands. It failed and Venizelos fled into exile in Paris. He died a year later. (Heneage, 2021, p. 178)

The failed coup gave the anti-Venizelist the opportunity to lead in front of a court martial 1,130 Venizelist members of the army, politicians, and civilians. Sixty of them were sentenced to death of which 55 had already escaped abroad. Of the remaining five, two were finally pardoned and three were executed including generals Papoulas and Koimisis, protagonists during the trial that led to the ‘execution of the six’, that had never been forgotten by the anti-Venizelists. Nevertheless, the latter avoided a wider purge to avoid a prolonged conflict. Furthermore, the executions met the opposition of France and Great Britain. (Dafnis, 1997, pp. 772-779)

The same way that a successful Venizelist coup led to the fall of the dynasty in 1924, the unsuccessful coup of 1935 led to its restoration. In fact, it took yet another coup, within the anti-Venizelist ranks this time, led by lieutenant general Kondilis, for the recall of king George II. The restoration was confirmed with a Soviet-style highly questionable referendum, held in November 1935, that gave it 97.8 % of the votes. (Dafnis, 1997, p. 803) The king pardoned the participants in the March coup and elections were called for January 1936. (Dafnis, 1997, pp. 811-814)

Venizelists and anti-Venizelists emerged from the elections as equals. Although this was indicative of the public will for a coalition government (Dafnis, 1997, p. 816), the two factions once again failed to work together. Furthermore, the contacts of both with the Communist Party (Mavrogordatos, 2019, p. 81), holding 5.76 % of the votes and 15 sits in the parliament (Dafnis, 1997, p. 815), for the formation of a government backed by communist votes caused worries in the army. Thus, the king appointed in March major general Ioannis Metaxas, who we have met before as an emblematic figure of the pro-royalists and the anti-Venizelist ranks, minister of the military to restore discipline. (Dafnis, 1997, p. 818) He was promoted to the premiership the next month, when the prime minister Demertzis died suddenly of a heart attack. Public unrest and the need for seamless war preparation, as the clouds of war were gathering over Europe, provided Metaxa with the arguments that persuaded the king to allow for a dissolution of the parliament and the suspension of civil liberties in August. (Dafnis, 1997, p. 837) So began the 4th of August Regime.

The 4th of August Regime was Greece’s rather unconvincing experiment in fascism. There were, for example, organizations like the National Youth Organization, promoting self-discipline for the boys and preparing girls to be dutiful mothers, anti-communism propaganda and political arrests, but at the same time Metaxas was not racist and repealed some of the anti-Semitic legislation of previous regimes. (Heneage, 2021, pp. 179-180) Furthermore, the king remained strong and autonomous (Mavrogordatos, 2019, p. 85) and the country was not linked to the Axes Powers. On the contrary, Metaxas was a supporter of Great Britain. (Mavrogordatos, 2019, p. 90) Thus, when, on the night of 28 October 1940, the Italian ambassador Grazzi demanded that Greece surrender key strategic sites or else face invasion, Metaxas answered in French, the language of Democracy, ‘Non’, No, in Greek, ‘Ochi’. (Heneage, 2021, p. 183) Greece was at war. Again.

II Clientelism

For division and civil war to flourish, one needs at least two factions, in the case presented here Venizelists and anti-Venizelists, each with members ready to do whatever is necessary to prevail. This, in return for specific benefits. The phenomenon is called clientelism – namely, the distribution of benefits by politicians and political parties to their supporters in return for their votes, campaign contributions and political loyalty. (Trantidis, 2016, p. xi)

The origin of clientelism in modern Greek history goes back to the Ottoman occupation. Indeed, Ottoman oppression strengthened the importance of the family as an institution that more securely guaranteed the protection of its members, relatives, and friends. (Veremis, The Interventions of the Army in Greek Politics 1916-1936, 2018, p. 287) The phenomenon expanded when the newly founded modern Greek state, as we have seen in the previous parts of this series, failed to create institutions that would earn the trust of its citizens. Everyday experience taught that a relationship with a powerful patron was better guarantee of service than trust in an indifferent state apparatus. Thus, the individual was connected to the institutions of power through some powerful patron-mediator in order to promote his interest rather than waiting for the state institutions to function properly. (Veremis, The Interventions of the Army in Greek Politics 1916-1936, 2018, pp. 278-279)

Although individual clients are, more or less, powerless, they can form networks and become important and valued for their patrons. Clients may be members of formally autonomous social institutions such as labor unions. Through this membership, they undertake overlapping roles: they are both political clients claiming individual patronage benefits and members of an organization claiming ‘collective’ or ‘club’ goods. Rather than isolated individuals, clients organized in party bodies, trade unions or other professional organizations can find in them the infrastructure by which they could hold patrons accountable. (Trantidis, 2016, p. 12)

Thus, for the interwar period studied here, the phenomenon of clientelism was probably most profound in the army. Already before the Balkan Wars, the then crown prince Constantine had created a small entourage of officers, which he promoted based not so much on their military performance but mostly on their loyalty to the dynasty. (Veremis, The Interventions of the Army in Greek Politics 1916-1936, 2018, p. 21) The ten years war period from 1912 to 1922, though, created a plethora of officers forged at the battlefield, outside of the military academy in Athens and the king’s cycle. In fact, by 1922 these officers made three quarters of the officer’s corpse. (Veremis, The Interventions of the Army in Greek Politics 1916-1936, 2018, p. 102) Probably the most astonishing example of rise in the army ranks during this period was the mutineer Plastiras, whom we met in the previous section, and who had started his career as corporal back in 1903.

For the conscripts that made it to the officers ranks the army also became a means of livelihood, but when the wars were over, they had the fewest guarantees of permanence (or further promotion). Thus, patronage was particularly important for those officers that came from the ranks of the reservists. (Veremis, The Interventions of the Army in Greek Politics 1916-1936, 2018, p. 102) The officers that could not find a patron within the royalists’ ranks, naturally, turned to the Venizelist – democratic space for protection.

It is certainly a paradox that parties competing for parliamentary rule within a nominally democratic framework possess military client-branches and that that they use these branches dynamically to influence the election process or even to overturn its results, when considered unfavorable. In fact, from the 43 military interventions between 1916 and 1936 only two presented the army as a supporter of liberal reform, a defender of the country’s territorial integrity and a punisher of those responsible for a national catastrophe. These were the revolt of the National Defense Committee in Thessaloniki in 1916 (Papageorgiou, History is Now Magazine, 2022) and the army’s revolt of 1922 discussed above. Both gained national significance and were supported by a large portion of the public. The rest were only intended to serve private interests or were an expression of discontent of some military faction. (Veremis, The Interventions of the Army in Greek Politics 1916-1936, 2018, p. 280)

It should be noted though that the officers do not always work in coordination with their political patrons. Movements like that of 1922, when the military for the first time fully assumes the exercise of government, contribute to the emancipation of some military factions from political patronage towards an autonomous claim of the benefits of power. (Veremis, The Interventions of the Army in Greek Politics 1916-1936, 2018, pp. 118-119)

The effect of clientelism on the social, political, and economic life in Greece has been discussed in more detail recently, because of the most recent economic crisis that started in 2010. Thus, we will return to it when recounting later periods of modern Greek history. Before I close this short reference to the subject here though, I further note that clientelism should not be seen as a political choice that is alternative to campaign strategies that seek to attract voters with programmatic commitments and ideology. In addition, clientelism must not be seen simply as a strategy of vote buying. Instead, organized clientelism, as described above, strengthens the capacity of political parties to recruit groups as campaign resources in order to appeal to voters via the conventional means of programmatic and ideological messages. (Trantidis, 2016, p. 10)

Clientelism as a method of political mobilization creates a strong preference for a political party in government to preserve policies that cater to clientelist demands and avoid policies that could limit the allocation of benefits and resources to their clients. (Trantidis, 2016, p. 17) This, in turn, limits the capacity for reform, especially during political and economic crises, as politicians in a highly clientelist system will try to preserve clientelist supply as much as possible. (Trantidis, 2016, p. 19) This will help us understand the problems of the Greek economy presented in the next section.

III Economy in crisis

Although the ten-year war period, between 1912 and 1922, ended with a catastrophe, interwar Greece was different from Greece before the Balkan Wars. Its population and territory had doubled: before the war Greece was made up of 2,631,952 inhabitants and its territory amounted to 63,211 square kilometers. By 1920 the population reached 5,531,474 and its territory 149,150 square kilometers. Finally, the census of 1928 recorded 6,204,684 inhabitants and a territorial expanse, after the catastrophe of the Asia Minor Campaign and the settlements that followed, of 129,281 square kilometers. (Kostis, 2018, pp. 272-273) Of course, most of these gains had already been achieved by 1913 and the expansion of the war period, including internal turmoil, to 1922 simply postponed the integration of the new territories to the country and its economy. Not only that, but it made it more difficult as by the end of the war the country was left much poorer and in a much less favorable international position.

The situation was made worse by the arrival in Greece of more than 1.2 million refugees as the result of the uprooting of the Greek communities in the East, following the defeat of the Greek army there. (Mavrogordatos, 2019, p. 157) The number represented 20 percent of the total national population and the country had to import significant quantities of goods in order to meet the emergency needs of these new populations. (Kostis, 2018, p. 279)

The arrival of the refugees was decisive for the ethnic homogeneity of Greece though. Following the treaty for the obligatory exchange of populations signed between Greece and Turkey in Lausanne in January 1923, and another one, this time for an exchange on a voluntary basis, between Greece and Bulgaria earlier, in 1919, 500,000 Muslims and 92,000 Bulgarians left Greece in the period that followed. (Kostis, 2018, p. 275) Thus, about 70% of the refugees that remained in Greece (about 200,000 left Greece to seek their fortunes elsewhere (Kostis, 2018, p. 275)) was settled in rural areas of Macedonia and Thrace taking up the fields and the houses of the Turks and Bulgarians that left. (Mavrogordatos, 2019, pp. 159-160)

The properties of the minorities that left Greece though could make for no more than 50% of what was necessary for the refugees in the rural areas. The other 50% came from a significant reform under the military regime of Plastiras in February 1923. That was the obligatory expropriation of the large country estates and real estate in general, without the requirement that the owners be fully compensated first. (Mavrogordatos, 2019, pp. 30, 369-373) This Bolshevik-like approach created many small owners in the countryside and actually kept the refugees away from the grasp of the Communist Party that additionally adopted the policies of the Communist International and promoted the autonomy of Macedonia and Thrace. (Mavrogordatos, 2019, pp. 383-391)

In fact, as the catastrophe of the Asia Minor campaign took place under anti-Venizelist rule and the rehabilitation and assimilation of the refugees is credited to the Venizelists, most of the refugees became clients of the Venizelist parties affecting the results of elections to a significant degree. (Mavrogordatos, 2019, pp. 134-140,152,154 ) Indeed, when a small percentage of the refugees abandoned the Venizelist camp in 1933, it reshaped the political balance and eventually led to an anti-Venizelist victory.

One more conclusion can be drawn at this point. The inability of a clientelist state for reform explains why, in several cases, this (the reform) comes from authoritarian regimes or dictatorships, like that of Plastiras that brought the agricultural reform. Consequently, these regimes remain practically unchallenged by the political establishment, like that of Metaxas after 1936 (Dafnis, 1997, pp. 880-881), that introduced a full social security plan and imposed compulsory arbitration in labor disputes to prevent social unrest. (Veremis & Mazower, The Greek Economy (1922 - 1941), 2009, p. 85) In any case, for reform or private interest (see section II), the collaboration between the politicians and the military officers (often based on a patron – beneficiary, that is clientelism, relationship) explains also why many military interventions went practically unpunished or why amnesty was very often granted to the protagonists during the periods of modern Greek history we covered so far.

The agricultural reform alone was not enough to settle the refugee’s problems. The country was lacking raw materials, equipment, and the necessary infrastructure to integrate the new territories to the state. As usual, Greece resorted to external borrowing to cover these needs. A 12,000,000-franc loan was granted to Greece on humanitarian grounds by the Refugee Settlement Commission under supervision of the League of Nations to be spent on rehabilitating refugees (Kostis, 2018, p. 279). Venizelos’ investment program (see section I) between 1928 and 1932 also increased the external national dept from 27,8 billion drachmas to 32,7 billion drachmas. (Veremis & Mazower, The Greek Economy (1922 - 1941), 2009, p. 77) This insured that a disproportionately large portion of the national budget would be used for debt payments: 25.6% of public revenue in 1927-28, 40.7% in the following year, while in the last of Venizelos’ four years the figure settled at 35%. These figures left little room for flexibility in the government’s budget. (Kostis, 2018, p. 286)

Flexibility was further reduced by the fact that more than 100 years after the establishment of the modern Greek state 70-80% of the country’s export profits was still coming from the cultivation of currant and tobacco. (Veremis & Mazower, The Greek Economy (1922 - 1941), 2009, pp. 77-78) The industry’s share to the GDP increased from 10% in 1924 to 16% in 1939, nevertheless, this development was carried out under protectionism conditions and did not introduce qualitative improvements in the Greek industry that would prepare it for international competition. (Veremis & Mazower, The Greek Economy (1922 - 1941), 2009, p. 87) Both remarks are indicative of the effect of clientelism on the lack of economy reforms and as an observer put it, positive developments in economic growth were more the result of the efforts of individual cultivators and industrialists rather than of a planned government policy. (Veremis & Mazower, The Greek Economy (1922 - 1941), 2009, p. 84)

Eventually, one more of the vicious cycles of the Greek economy, proposed by Dertilis (Dertilis, 2020, p. 29), was repeated in the interwar period. Once again it started with war or preparation for war (military spending took 18% of the GDP between 1918 and 1822 (Dertilis, 2020, p. 99)) and culminated to the suspension of national dept servicing on 1 May 1932. The government also abandoned the gold standard, and the value of the drachma began to fluctuate freely. Strict measure for limitations on currency followed that would affect the Greek economy for many decades. (Kostis, 2018, p. 287)

The Greek economy then turned inwards and seeked to develop by exploiting its domestic resources and more centralized forms of economic management made their appearance as the state took on a leading role. The economy recovered, but this recovery did not solve the country’s economic woes. (Kostis, 2018, p. 287) By 1937, the deficit in Greece’s trade balance reached 5,649 million drachmas. A year later, Greece imported three quarters of the raw materials used by its industry, one third of the cereals needed for domestic consumption and significant amounts of machinery and capital goods. By March 1940, the nominal public dept had reached 630 million dollars, equivalent to 9.25% of the national income for Greece (this reflected to a great extent the prevailing situation till 1932, as since then borrowing was significantly reduced) compared to 2,98% for Bulgaria, 2,32% for Rumania, and 1,68% for Yugoslavia. (Veremis & Mazower, The Greek Economy (1922 - 1941), 2009, pp. 88-89) Military spending was reduced to 6.2% of the GDP between 1934 and 1939 (Dertilis, 2020, p. 99) but the imminent second world war did not allow for further reductions. In fact, at the end of 1939, when the war in Europe began, the Greek government spent an additional amount of 1,167 million drachmas for military purposes. This unexpected expense burdened the state budget by 10%. Between July 1939 and October 1940, when Italy attacked Greece, the circulation of banknotes increased from 7,000 million to 11,600 million drachmas and the wholesale price index increased by 20%. (Veremis & Mazower, The Greek Economy (1922 - 1941), 2009, p. 90)

Thus, the Italian attack in October 1940 found Greece’s economy in a fragile state and as is very often the case, an economy in crisis invites foreign intervention. (Dertilis, 2020, p. 29)

IV Foreign intervention

Foreign intervention refers basically to that of the Great Powers of the time (Great Britain, France, Russia, Austria – Hungary, the German Empire/Germany, Italy, and the United States of America). That is because the interaction of modern Greece with its Balkan neighbors was rather antagonistic, if not hostile, and more often than not determined by the dispositions of the Great Powers. (Divani, 2014, σσ. 82 - 119) Exception is the short period of the Balkan Wars, when skillfully chosen alliances with its Balkan neighbors resulted in the doubling of Greece’s territory at that time. (Papageorgiou, History is Now Magazine, 2022) A significant improvement in the relation with its neighbors, Albania, Yugoslavia, Italy and Turkey, was also achieved, again under the premiership of Venizelos, between 1928 – 1932, allowing for a significant cut in military spending to the benefit of investments in infrastructure and the rehabilitation of the refugees. (Divani, 2014, pp. 207-208) (see also section I above). In fact, a treaty of friendship was signed between Greece and Turkey in October 1930.

It goes without saying that state characteristics like the ones presented previously (division, civil war, economy in crisis) facilitate, if not invite, foreign intervention. Furthermore, the term (‘foreign intervention’) is perceived, in most cases, with a negative sign. It is synonymous to the limitation (or even loss) of a state’s sovereignty at the interest of a foreign power. Nevertheless, let us remember, at this point, some cases of foreign intervention that we have come across in this series on the history of modern Greece: i) at a critical point of the War of Independence, when defeat seemed imminent, the combined fleets of Great Britain, Russia and France defeated the Ottoman-Egyptian forces at Navarino Bay and later signed the Protocol of London granting autonomy to Greece (Papageorgiou, History Is Now Magazine, 2021), ii) the first territorial expansion of Greece to the Ionian Islands came as a ‘dowry’ to the new king George I in 1864, (iii) the second territorial expansion of Greece to Thessaly in 1881 came after the Great Powers intervened to revise the Treaty of St Stefano and cancel the creation of the ‘Great Bulgaria’, and (iv) when Thessaly was retaken by the Ottomans after the Greek defeat in the 1897 Greco-Turkish war the Powers once again intervened to keep Greece’s territorial losses to a minimum. (Papageorgiou, History is Now Magazine, 2021)

Are we then to conclude, following the previous remarks, that foreign intervention was out of pure concern for the well-being of Greece? By no means. Great Britain’s intervention at Navarino, together with France and Russia, intended to the limitation of the latter’s influence in the region. That is why immediately afterwards Great Britain worked to preserve the integrity of the Ottoman Empire by keeping Greece’s original territory very limited. The Ionian Islands were also given to Greece at a period when their value for Great Britain was deemed limited and under the condition that they would be rendered demilitarized. The limitation of Russia’s influence in the Balkans was also behind the revision of the Treaty of St Stefano. And there were also cases, as for example during the Asia Minor Campaign, that the Great Powers simply abandoned Greece to suffer a disastrous fate. (Papageorgiou, History is Now Magazine, 2022) Thus, the remark that foreign intervention is synonymous to the limitation (or even loss) of a state’s sovereignty at the interest of a foreign power remains valid. Indeed, with some exceptions, e.g. during the Balkan Wars, Greece failed to keep its fate in its own hands. The previous discussion serves only to show that foreign intervention was also positive when, by mere chance, foreign interests coincided with those of Greece.

But is it generally easy for a small state to draw an independent policy? Certainly not. Things are even worse though, when clientelism governs its political, social, and economic life. In fact, during the interwar period, the small states had the chance to participate to an international forum where, for the first time, instead of being subjected to the decisions of the Great Powers, they could, even to a small extent, co-shape them. This was the League of Nations (LoN). (Divani, 2014, p. 134)

Greece’s initial experiences with the first global intergovernmental organization, founded in 1919, were not good though. When Italy invaded Corfu in August 1923 (see section I) the LoN did very little to contain Mussolini. This was the first indication of the flaws of the LoN that eventually failed to work effectively against the fascist aggression that culminated to the Second World War. On the contrary, when Greece, under Pangalos’ dictatorship invaded Bulgaria (see section I) the LoN moved swiftly to condemn and punish it. The feeling of injustice was strong, but Greece, once again at a weak spot, could not do much to expose the handlings of the LoN. It needed the latter for technical and financial support for the rehabilitation of the refugees following the disaster of the Asia Minor Campaign. (Divani, 2014, pp. 159-173)

Indeed, as the former prime minister A. Michalakopoulos’ put it in 1929, regarding the work of the LoN in Greece: ‘if the State attempted to do the work of the Refugee Settlement Commission the errors would be tenfold, and the work imperfect, and there would be multiple embezzlements and the costs would be greater’. (Mavrogordatos, 2019, p. 138) This was because the LoN took special interest in ensuring that the loan money would not be spent for reasons other than the productive and developmental settlement of the refugees. The Financial Committee of the LoN also demanded reforms aiming at the stabilization and modernization of the Greek economy. (Divani, 2014, p. 242) In fact, the financial control of the LoN coexisted with the International Financial Committee controlling the Greek finances already since 1897, after the military defeat by the Ottomans following the bankruptcy of 1893. (Papageorgiou, History is Now Magazine, 2021)

International financial controls mainly aim to serve the interests of Greece’s creditors. No doubt. Nevertheless, even to this end, they often introduce necessary economic, political (and consequently even social) reforms that have been repeatedly postponed and avoided by the local political establishment as they collide with the interests of the stakeholders of the clientelist state. Thus, foreign intervention represents an alternative to authoritarian regimes for the introduction of reform (see section III). Similarly though, it is used as scapegoat from the clientelist establishment, usually under the veil of an alleged insult to national sovereignty or democracy. As such it is hated by the Greeks that, in such a way, miss (or turn away from) the real origin of their troubles. Once again: a satisfactory solution of the refugee problem would have been impossible without the help of the LoN. (Divani, 2014, p. 293) As the Refugee Settlement Commission worked independently though, keeping the available resources (especially the refugee loans) away from the grasp of the local political establishment, its work was repeatedly discredited by the press and the Greek parliament in consecutive sessions discussed accusations against it. (Divani, 2014, p. 299)

V Conclusion

At the heart of all this trouble lies clientelism. The Greeks fought the War of Independence (1821 – 1830) to free themselves from the Ottomans only to become serfs to a clientelism system that significantly hinders their ability to develop and exploit the full capacity of themselves and the resources of their country. This is because the system demands unquestionable loyalty to the party or the ‘clan’. So unquestionable that one should be prepared to harm even its fellow Greek members of the opposite ‘clan’. Thus, civil war is a phenomenon often met in modern Greek history. This often takes the classical form of armed conflict, but, more often than not, is present in the form of ‘exchanges’ in critical administration positions. Members of one ‘clan’ are usually kicked out when the next ‘clan’ comes to power and needs to ‘accommodate’ its own clients. This non-meritocratic system of course guarantees that the country almost never has the needed capacity in these positions and if this, by coincidence, happens, it is never for a long time. Thus, Greece’s ability to keep up with the signs of each time is crippled. After all, with clientelism it is never about long-term planning and reform. Thus, the often bankruptcies. Then reform comes, usually violently, from inside or the outside. Because a divided nation invites foreign intervention.

It is not to be considered that all Greeks participate or are being favored by the clientelism system. Many have individually thrived inland or abroad when they found themselves in a healthier environment. And indeed the country has made progress since its establishment. Nevertheless, I dare to say that this was and remains slow, and it was and still is more coincidental. Sometimes because its interests coincided with those of the Great Powers of the time. Sometimes because it was lucky enough to have great individuals in power.

At this point, as the period we are discussing coincides with the death of Eleftherios Venizelos, some remarks about the Cretan politician are necessary. As we have seen he was not a role model for parliamentarism. He did not hesitate to resort to arms or even divide the country when necessary. So should he be condemned as, at least at times, anti-democratic? Maybe. I propose though that, at the same time, he was simply being realistic. Venizelos knew how the system works. He saw the opportunity for Greece’s expansion and he wanted to take it. He knew that clientelism would slow things down and the opportunity might have gone missing. So he played by the real rules of the game. That of clientelism. Not “parliamentarism” or “democracy”. And if, for example, Napoleon of France squandered French power and prestige leaving France smaller than he found her and is still called ‘The Great’, (Kissinger, 2022, pp. 61-62) Venizelos was proved to be ‘Great’.

So, should the country continue to rely on chance and a few good, or even ‘Great’, men or women for its progress? That would be a great risk. Because clientelism is like the cancer developed in a certain part of the body. If not treated properly, it will soon drag the healthy parts of the body to death as well.

What do you think of the period 1923-40 in the Modern Greek State? Let us know below.