James Buchanan was US President from 1857-1861. He is often considered one of the worst presidents of the US, with his presidency leading up to the US Civil War. Here, Ian Craig takes a look at Buchanan’s presidency. He starts by arguing that, in spite of his Democratic Party generally favoring slavery, what are often seen as pro-slavery actions during the Bleeding Kansas crisis (1854-1861), actually led to Kansas becoming an anti-slavery state.

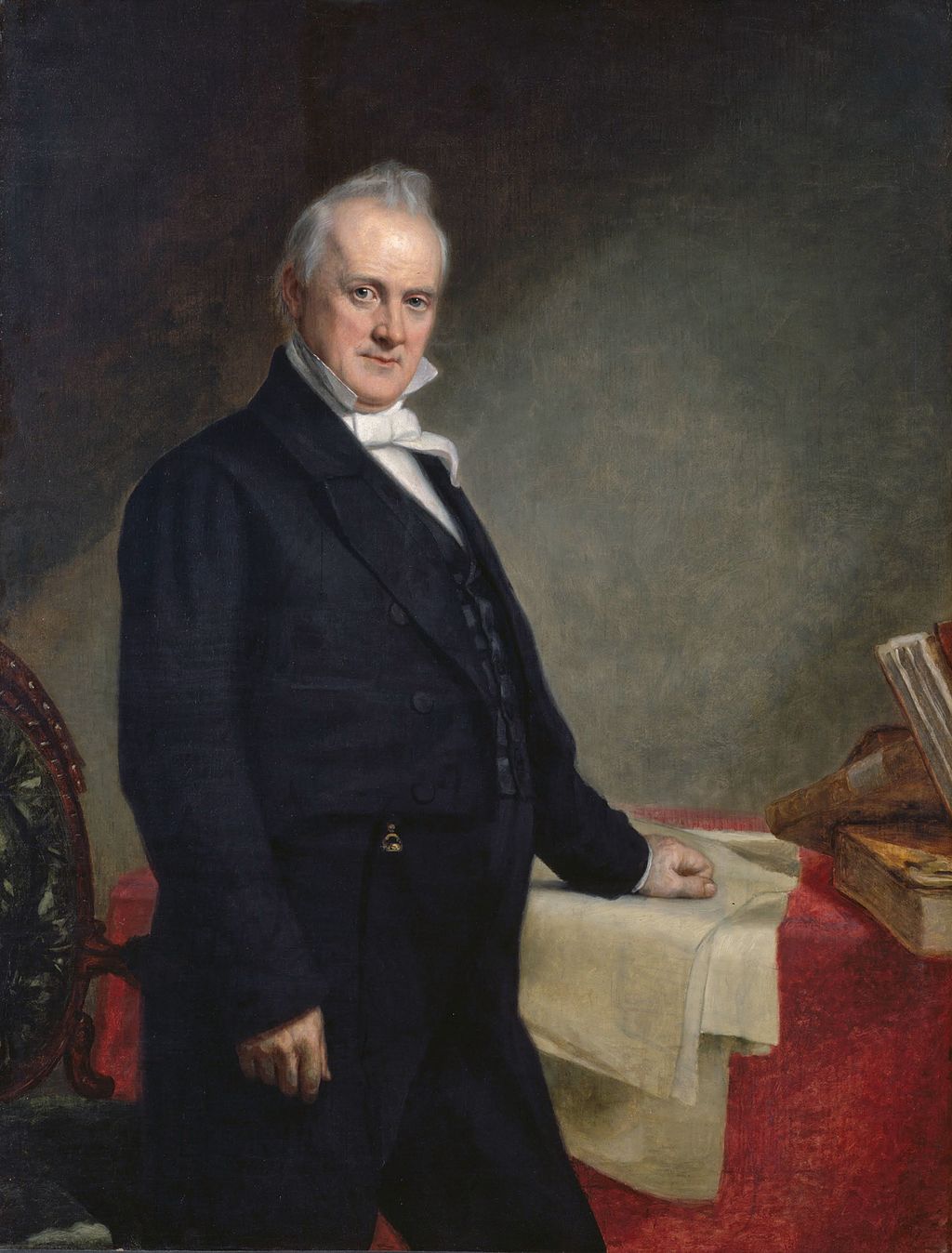

1859 portrait of President James Buchanan. Painting by George Peter Alexander Healy.

Of all the presidents in the history of the United States, none have been as ridiculed as the man who became the fifteenth president on March 4, 1857. Having secured the Democratic nomination in 1856, James Buchanan had little trouble defeating the Republican Party’s first candidate John C. Frémont and former president Millard Fillmore. At the time of his election, Buchanan was the nation’s most qualified person to hold the office of chief executive. Having been a lawyer, state legislature, U.S. representative, U.S. Senator, minister to both Russia and Great Britain, and Secretary of State, Buchanan remains one of the only presidents in U.S. history to have an extensive public service background. The question then remains is, why he is considered the worst president in history and why is he blamed for the Civil War? These questions will be answered over a series of articles sequencing key events in Buchanan’s presidency.

Kansas-Nebraska Act

In his last message to Congress on January 8, 1861, Buchanan stated that, “I shall carry to my grave the consciousness that I at least meant well for my country.”[1]Since that time, over one hundred and fifty years have past since he left office and the Civil War concluded. However, his legacy remains plagued by the questions posed above. To really understand the actions taken by Buchanan leading up to the outbreak of Civil War, one must look into the political climate of the time as well as the personal beliefs that shaped Buchanan’s governing style.

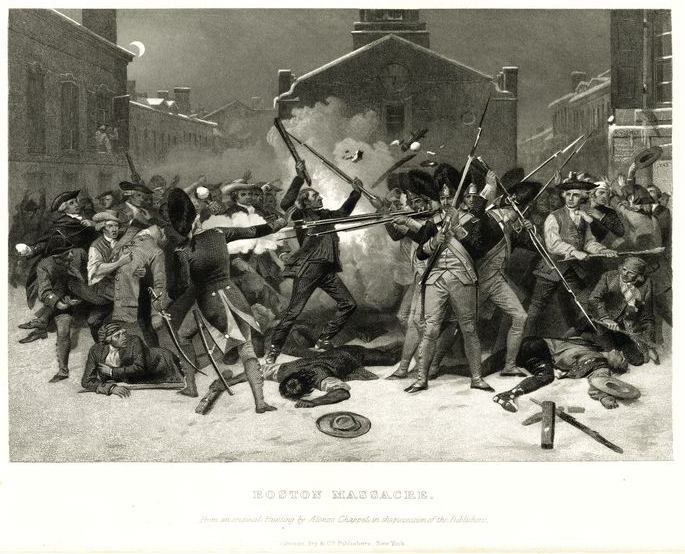

One particular event that would have a direct impact of Buchanan once he became president was the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854. This allowed for Kansas and Nebraska to create governments and decide for themselves the slavery question while also repealing the Missouri Compromise of 1820. Pro-slavery settlers from neighboring Missouri crossed the border illegally into Kansas, heavily influencing the election of a pro-slavery government in Kansas. This led to violence in the territory as both pro-slavery and anti-slavery groups fought for control. It also led to the creation of two governments, one at Lecompton (pro-slavery) and one at Topeka (anti-slavery). This series of events later became known as “Bleeding Kansas” for the violence and death that occurred. Even the United States Senate was not spared from the violence. In 1856, Senator Charles Sumner was beaten over the head with a cane by Congressman Preston Brooks on the floor of the Senate. Sumner had called out a relative of Brooks regarding the slavery issue offending his honor. Lecompton was also recognized as the legitimate government despite hostilities.

Dealing with Bleeding Kansas

Upon assuming office, Buchanan had to deal with the crisis in Kansas left to him by his predecessor Franklin Pierce. Pierce had signed the Kansas-Nebraska Act believing that territories were “perfectly free to form and regulate their institutions in their own way.”[2]However, Pierce would come to favor the pro-slavery legislation over that of the anti-slavery actions. James Buchanan’s views of the Kansas-Nebraska Act were not favorable. He wrote that “Congress which had commenced so auspiciously, by repealing the Missouri Compromise…reopened the floodgates of sectional strife.”[3]The governing style of James Buchanan was one based on that of a diplomat. Having an extensive background as a negotiator, he used his prior experience in his many diplomatic and legislative roles as chief executive. He also heavily relied on his days as a lawyer and his knowledge of constitutional law to formulate his opinions. This is how he dealt with the crisis in Kansas.

As president, Buchanan believed that he did not have the authority to interfere in the elections which took place in Kansas despite the fraud that had occurred there. He wrote that “it was far from my intention to interfere with the decision of the people of Kansas wither for or against slavery.”[4]Essentially, Buchanan felt that the people of Kansas could settle the matter themselves without government intervention. Despite his intentions, Buchanan took military action in sending federal troops to Kansas in 1857 to secure the legitimacy of a state constitution without fraud or violence. His justification for this was that it was his duty to protect the recognized government and the people’s wishes as President of the United States. Buchanan recalls, “under these circumstances, what was my duty? Was it not to sustain this government (in Lecompton)? To protect us from the violence of lawless men, who were determined to ruin or rule? It was for this purpose, and this alone, that I ordered a military force to Kansas.”[5]

In doing this, Buchanan was criticized for appearing to support the pro-slavery party in creating a slave state. This, however, was not the case as he attempted to perform his duties in executing the laws and by preserving and protecting the Constitution. He states in a broad question to such people, “would you have desired that I abandoned the Territorial Government, sanctioned as it had been by Congress, to illegal violence…this would, indeed have been to violate my oath of office.”[6]Standing firm on his beliefs, Buchanan was convinced that his action would help to support a positive and legal result at the next election. To him, it was still up to the people to decide on the manner.

1858 Kansas Election

In early 1858, a new election was held to elect state officials based on the passage of the constitution in November. This election for governor, lieutenant governor, and other officials, resulted in the election of several members of the anti-slavery Topeka Convention. The balance of power shifted towards them and they were more determined to vote in the creation of a constitution with some aspects of the Lecompton Constitution. James Buchanan took this as a victory because he had wished that the anti-slavery party would take part in the elections. Buchanan, writing in the third person, states that “it had been his constant effort from the beginning to induce the Anti-Slavery party to vote. Now that this had been accomplished, he knew that all revolutionary troubles in Kansas would speedily terminate. A resort of the ballot box, instead of force, was the most effectual means of restoring peace and tranquility.”[7]Buchanan, keeping to his constitutional beliefs, used force only to enforce the rights of the people to vote under the Constitution. Essentially, Buchanan gave the anti-slavery party the tools to vote in a free and fair election without fear of violence. It only took them a while to take him up on his efforts before they would vote in the government. James Buchanan recognized that they were in effect the majority of the population and in accordance with the law, it was up to them to decide the slavery question.

On February 2, 1858, James Buchanan gave a message to Congress regarding the constitution of Kansas. The newly elected government (with a large majority of anti-slavery supporters) had sent the Lecompton Constitution (with slavery elements) to the president for Congressional approval. In Buchanan’s message he stated that “slavery can therefore never be prohibited in Kansas except by means of a constitutional provision, and in no manner can this be obtained so promptly.”[8]Although this may be interpreted as pro-slavery, to Buchanan it was not, because the people of Kansas had elected their leaders and had submitted a constitution in forming a state legally. It was his duty to ensure that their wishes were carried out. He warns that, “should Congress reject the constitution…no man can foretell the consequences.”[9]In Buchanan’s eyes, the admittance of Kansas into the Union in a timely manner would “restore peace and quiet to the whole country.”[10] In closing his message to Congress, he admits that he had been forced to act in Kansas on behalf of the people to ensure fair elections and opportunities for both sides. He states of the matter, “I have been obliged in some degree to interfere with the expedition in order to keep down rebellion in Kansas.”[11]

Buchanan and the Constitution

Although Congress would reject the Lecompton Constitution due to the slavery elements, James Buchanan could not interfere as it was not in the powers of the executive granted in the Constitution. In 1861, Kansas became a free state. In looking at the situation in Kansas, James Buchanan’s actions were in accordance with the Constitution and his role as chief executive. Since the Lecompton government was established by Congress it was the legal government in Buchanan’s eyes. He recognized that voter fraud and violent intimidation had elected pro-slavery delegates that did not speak for the majority of Kansas. It was for this reason that he urged them to have new elections which were fair. When that advice fell on deaf ears, he sent federal troops to defend the rights of the people at the ballot box. This action was taken as his support of the pro-slavery election results. However, it gave the anti-slavery party the ability to vote in unbiased elections which would lead to their control of the government. In the words of James Buchanan, “I have thus performed my duty on this important question, under a deep sense of responsibility to God and my country.”[12]

What do you think of James Buchanan’s actions during Bleeding Kansas?

[1]Irving Sloan, James Buchanan: 1791-1868, (New York: Oceana Publishers, 1968): 84.

[2]Michael F. Holt, Franklin Pierce, (New York: Times Books, 2010): 77.

[3]James Buchanan, Mr. Buchanan’s Administration on the Eve of Rebellion, (Scituate: Digital Scanning Inc, 1866/2009): 13.

[4]Sloan, 35.

[5]Buchanan, 18.

[6]Buchanan, 18.

[7]Buchanan, 24.

[8]Sloan, 47.

[9]Sloan, 47.

[10]Sloan, 48.

[11]Sloan, 49.

[12]Buchanan, 26.