Different Roles on the Plantation

Gone with the Wind was largely realistic in showing how white and black people had different roles on the plantation. In the film, Tara and Twelve Oaks serve as social settings for their white residents. Firstly, the plantation houses are home to the O’Hara and Wilkes families respectively. Secondly, the houses serve as a place for social gatherings. At Tara and Twelve Oaks, Scarlett entertains admirers such as Brent and Stuart Tarleton. The plantation itself, however, serves distinctly financial purposes – the growing of cotton. For the black residents of the plantation, this means work for Big Sam the foreman and the field hands he leads, as shown in the scene where the men toil in the fields till it is “quitting time” at sunset.[1] Not only do the slaves work in the fields, they also work in the houses. The film shows how Mammy, Prissy, and Pork serve their white masters at Tara, and how other domestic servants wait on the guests at the Twelve Oaks party. Thus, Gone with the Wind establishes the plantation as a place of riches and recreation for white Southerners, and a place of work and servitude for black Southerners.

Yet, the film’s portrayal of white activities on the plantation is extraordinary, for the plantation lifestyle was enjoyed only by a minority of people. Only 12 percent of slaveholders held twelve or more slaves, which was the dividing line frequently given between a plantation and a farm.[2] Furthermore, while some planters lived in grand two or three-story Greek Revival or Federal mansions, even these houses were not as majestic as the Tara house, which was compared by the film’s makers and consultants to the State Capitol at Montgomery, Alabama.[3] The social life thus enjoyed by white people at Tara and Twelve Oaks was enjoyed only by a minority of Southerners in reality.

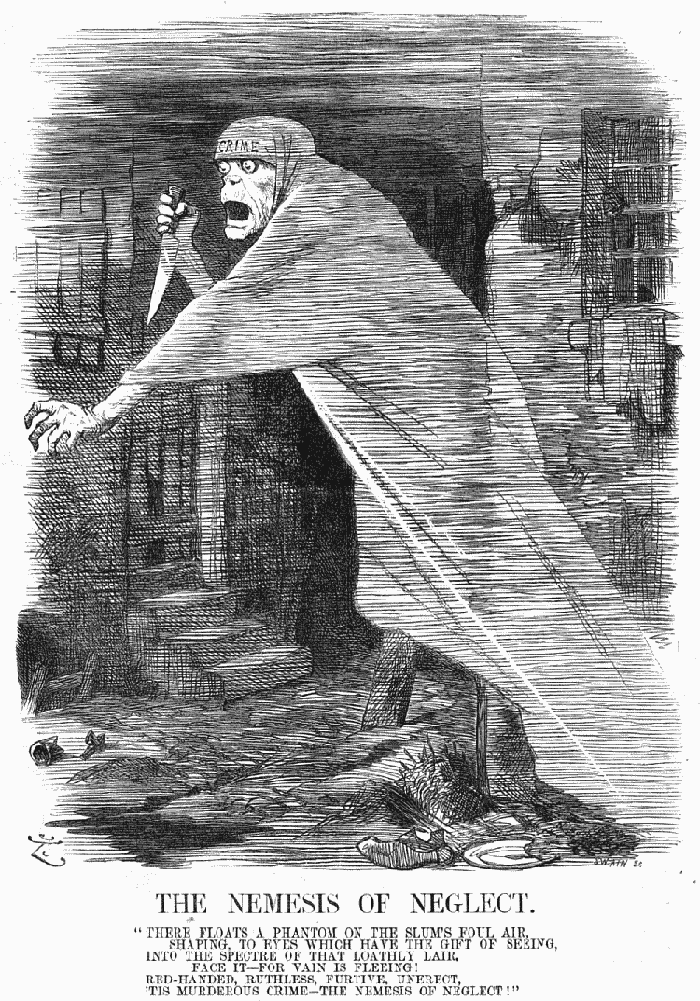

Black plantation life was also idealized, for the portrayal of slaves being happy, contented, and well-treated was not representative of the experience of many slaves. For one, numerous slaves went hungry because their stingy masters failed to provide them adequate rations.[4] Other slaves had to work in hostile conditions. Lu Lee, an enslaved person from Texas, was made to herd sheep in the prairies despite the dangerous wolves, panthers, and wild cattle that roamed about.[5] For many, slavery was an arduous experience markedly different from the peaceful scenes of ploughing and cattle herding shown in Gone with the Wind.

Relations of Power and Authority

The film also shows the dynamics of power and authority between white and black people on the plantation. White people assert a formal (but benign) authority over black people. The black house servants are obliged to perform tasks for their masters and mistresses when requested to do so. Early in the film, Mammy helps Scarlett with her dress, while Prissy delivers “vittles” on a tray.[6] Black people are shown to have an informal authority over white people as well. Mammy harangues Scarlett over eating, napping, and behaving at the party. Neither is she abashed about comparing Scarlett and Suellen to “poor, white-trash children” when they bicker over Ashley.[7] The harmonious co-existence of slave and master strengthens the film’s wistful, nostalgic portrayal of a bygone age.

Nevertheless, such interactions between slave and master may be atypical. Not all slaveholders were as benevolent as Gerald O’Hara, who believed that “one must be firm with inferiors but … be gentle with them.”[8] Slaves were whipped for offences such as escaping, dishonesty, indolence, stealing, and showing disrespect to their masters. Solomon Northrup’s account of life on a Louisiana cotton plantation evinces the clear authority of the master to abuse his slaves. In his famous Twelve Years a Slave, Northrup describes how new slaves were “whipped up smartly” before being sent into the field to pick cotton as fast as possible.[9] Thus, the relatively violent-free treatment of slaves shown in the film was unrepresentative of all plantations.

Impacts of the Civil War

These interactions within and between white and black people were not to last. The Civil War, and its wave of destruction across the South, led to an upheaval of the Southern landscape and way of life. For white people, the plantation became a site of Northern defilement and exploitation. Upon her return from Atlanta, Scarlett finds that Twelve Oaks has been left in ruins. At Tara, she is informed by Pork that “the Yankees done burned [the barn] for firewood.”[10] She is then informed by Mammy that the Union soldiers “stole most everythin’ they didn’t burn,” including the clothes, rugs, and even rosaries, and that “there ain’t nothing to eat.”[11] To add further insult to injury, a lone Union cavalryman sneaks into the Tara house and attempts to steal the O’Hara’s jewelry. Such rapacious Union soldiers contributed to the breakdown of white society. The comfortable plantation life as Southerners knew it simply became non-existent.

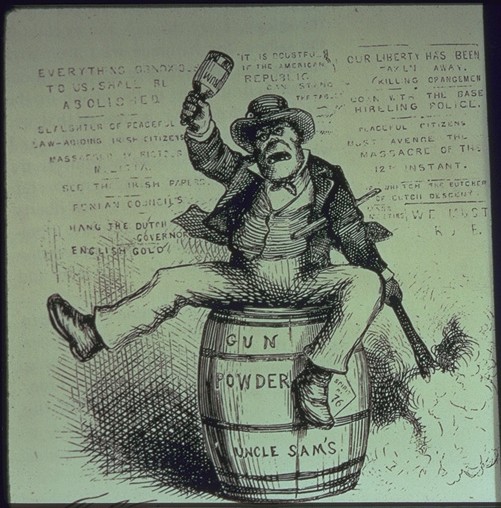

The film’s representation of the dismal state of the South is truthful. Union soldiers certainly partook in pillaging plantations and the rest of the former Confederacy. Like the members of the O’Hara family, Mrs. Mary Jones and her daughter (both of Liberty County, Georgia) found themselves raided by Yankees. These soldiers stole food and rifled through the women’s personal belongings.[12] Other bands of soldiers, known as “Sherman’s bummers,” also pillaged livestock from farms and plantations.[13] The plantations that survived Union destruction were unable to sell their products during the war. In the Reconstruction era they suffered further from severely depressed prices. Thus, the victimization and poverty of plantation owners was no exaggeration in Gone with the Wind. The sense of normalcy and security they once had was directly and permanently violated by the Union movement into the South.

So too was there an upheaval in the status of African Americans. Their emancipation shifted the racial dynamic which had given power to white Americans. In the film, this is evidenced by the triumphant black carpetbagger who sings “Marching Through Georgia” as he travels by horse carriage along the roads of the Southern countryside. While the film depicts such changes for northern blacks, it shows the southern black servants faithfully standing by the O’Hara family when Scarlett returns. Mammy washes the clothes of the returning Confederate soldiers and helps Scarlett to make a dress out of her mother’s portieres. Pork assists by getting the horse shod and by stirring the soap when instructed by Scarlett to do so. The film thus shows that even as northern blacks challenged the prewar notions of black inferiority, some slaves continued in servitude to their masters.

For a variety of reasons, slaves continued to serve their masters. Many slaves, including children and adults, appeared unwilling to leave the places where they had lived and worked.[14] They considered such places home, even if they loathed their subjugation there. Some slaves remained loyal to their masters because the latter had been kind to them.[15] Others stayed with their masters because they feared the Union soldiers, who sometimes robbed them of their possessions.[16] Moreover, African American women were vulnerable to violent crimes: one female slave was raped in front of her white mistress, while another was drowned in a ditch.[17] It would not be unrealistic for slaves like Mammy, Prissy, and Pork to continue to serve the O’Hara family.

Still, most African Americans fervently wished for emancipation.[18] Even before the war ended, many black southerners participated in a massive labor withdrawal termed by W. E. B. Du Bois as the “General Strike.”[19] With white masters like Ashley Wilkes away on the war front, slaves seized the opportunity to work slowly, defy orders and instructions, move freely from one place to another, and engage in other activities that they had been disallowed from.[20] Slaves escaped as the war drew closer to the Southern homeland – one South Carolina planter, serving in the Army of Northern Virginia, was infuriated when his “faithful” body servant ran away.[21] As seen in Tara after the war, where it appears that there are no other slaves, Mammy, Prissy and Pork may have been the exception. Most slaves are likely to have stopped working as slaves for their masters.

Conclusion

Overall, the film is an overwhelmingly sympathetic portrayal to a lost Southern way of life, where the plantation is a place of tranquility, prosperity, and satisfaction. White people such as Scarlett and Gerald O’Hara are shown as benevolent masters, and black people such as Mammy and Pork are shown as willing and subservient slaves. In line with the Lost Cause interpretation of the Civil War, the Confederacy and its institution of slavery are portrayed as honorable. With slave and master happy with the status quo, notions of ending slavery (celebrated by the Emancipation Cause as the war’s aim) should be dismissed. The film also forces those who support the Union Cause to re-consider how honorable their cherished war heroes were. Collectively and individually, Yankees are shown to have driven Southerners to misery with their wanton destruction and pillaging of Southern plantations and their homes. Such dishonorable behavior by Union troops challenges the Reconciliation Cause as well, which celebrates equally the bravery of white Union and Confederate soldiers.[22] The film thus champions the Lost Cause over other interpretations of the Civil War.

However, the film’s portrayal of slave-master relations is on a whole unrepresentative of the entire experience of Southern slavery. Conditions of slavery within the United States varied from region to region, since slavery was present from Texas to Virginia. Slavery remained highly diverse even within regions. Slaves worked both in cities and in the countryside. Slavery also differed in scale: some owned one or two slaves while others owned hundreds. Undoubtedly, there were large plantations with luxurious houses and numerous slaves. So too were there owners who were even-handed and kind. Nevertheless, the portrayal of plantation slavery in Gone with the Wind likely represented the experiences of a privileged minority of Southerners.

Furthermore, the film’s portrayal of slavery shows that racist attitudes did not end with emancipation, but continued into the 20th century. The film includes the racial epithet “darkies,” which Gerald O’Hara used to refer to African Americans. More significantly, the film evokes the smiling complaisance of Mammy, Pork, and Prissy to suggest that black people were inclined to subordinate themselves to their white betters. Evidently, racism was still present five decades after the Civil War.

Gone with the Wind illuminates the roles of blacks and whites on plantations, the relations of power between them, and the impact of the Civil War on both. By contrasting the positive side of slavery and the negative aspects of Reconstruction, the film aides the Lost Cause interpretation of the Civil War. Slaves and masters are shown to lead parallel lives, living together, contented with their station. However, in reality, black and white lives were highly dissimilar. The film thus distorts the suffering and inferiority experienced by most slaves.

What do you think of the article? Let us know below…

[1] Gone with the Wind, directed by Victor Fleming. (1939; Burbank, CA: Warner Home Video, 2004), DVD.

[2] Gary W. Gallagher and Joan Waugh, The American War: A History of the Civil War Era (State College, PA: Flip Learning, 2016), 12.

[3] Christopher G. Bates, ed., s.v. "Planters and Plantations," in The Early Republic and Antebellum America: An Encyclopedia of Social, Political, Cultural, and Economic History (Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, 2010); and Jim Cullen, The Civil War in Popular Culture: A Reusable Past (Washington: The Smithsonian Institution, 1995), 90.

[4] Christopher G. Bates, ed., s.v. "Slavery, Life and Culture," in The Early Republic and Antebellum America: An Encyclopedia of Social, Political, Cultural, and Economic History (Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, 2010).

[5] Andrew Waters, ed., I Was Born in Slavery: Personal Accounts of Slavery in Texas (Winston-Salem, NC: John F. Blair, Publisher, 2003), 11.

[6] Gone with the Wind, directed by Victor Fleming. (1939; Burbank, CA: Warner Home Video, 2004), DVD.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Solomon Northrup, Twelve Years a Slave: Narrative of Solomon Northup, a Citizen of New-York (New York: Miller, Orton, & Mulligan, 1855), 165.

[10] Gone with the Wind, directed by Victor Fleming. (1939; Burbank, CA: Warner Home Video, 2004), DVD.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Jacqueline Glass Campbell, When Sherman Marched North From the Sea: Resistance on the Confederate Home Front (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003), 15-6.

[13] Ibid, 44-5.

[14] Campbell, 49.

[15] Ibid, 48.

[16] Ibid, 65.

[17] Ibid, 66.

[18] Gallagher and Waugh, 93.

[19] Ibid., 94.

[20] Ibid. 93.

[21] James M. McPherson, For Cause & Comrades: Why Men Fought in the Civil War (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997), 106.

[22] Gallagher and Waugh, 240.