The Inquisition was led by institutions in the Catholic Church and took on many forms over the centuries. Here we provide an overview of the history of the Inquisition, including witch-hunts, the Spanish Inquisition, and why the Catholic Church launched and maintained it for many centuries. Jessica Vainer explains.

Saint Dominic presiding over an Auto-de-fe by Pedro Berruguete.

When was the inquisition and what was its goal?

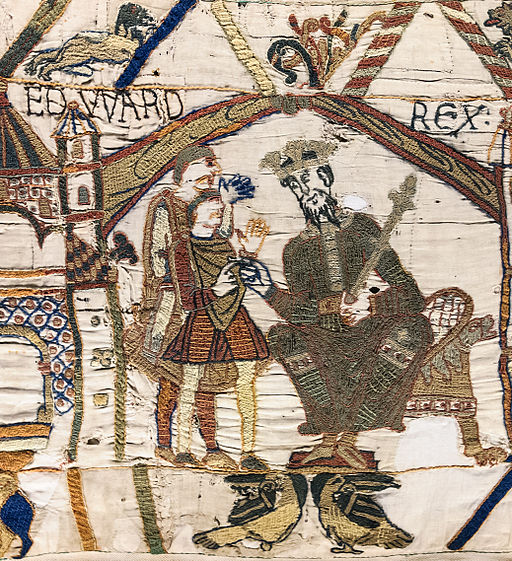

The Inquisition was established in twelfth century Western Europe by the Catholic Church and had the goal of fighting heresy and threats to Catholic religious doctrine. Initially the leaders of this Medieval Inquisition fought varied groups including Albigensians, Cathars, Manichaeans, Waldensians and other free-thinkers who tried to shake off Catholic doctrine.

Witches

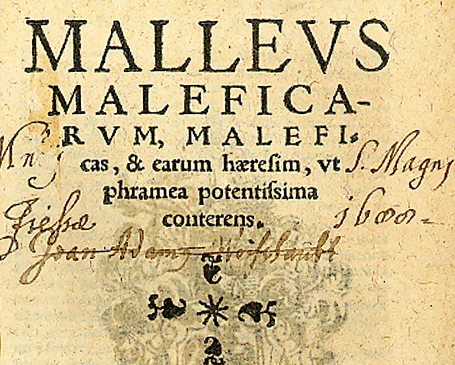

However, from the fourteenth and especially the fifteenth centuries, the Inquisition became more interested in witches. Sociologists talk about several reasons for why attention was placed on witches. But, a key reason was the fundamentally patriarchal nature of society at the time. And for a Catholic inquisitor living in such a society, the idea that if a woman caused certain problems, then she was a witch, was quite natural.

The custom of burning witches at the stake was more common in northern European countries, such as Germany, France, Ireland, and Britain.

One of the earlier such instances took place in 1324 in Ireland. Bishop Richard de Lestrade brought accusations against Lady Alice Kyteler for renouncing the Catholic Church. She was accused of:

Trying to find out the future through demons;

Being in connection with the "demon of the lower classes of hell" and sacrificing live roosters to him;

The manufacture of magical powders and ointments, with the help of which she allegedly killed three of her husbands and was going to do the same with the fourth. Possibly through this the bishop intended to settle personal accounts with the lady.

Witch-hunting became more common over time and one of the more shocking statistics is that in 1589, in the Saxon city of Quedlinburg, with a population of 10,000, 133 women were burned in one day. More broadly, while exact statistics are hard to come by, from 30,000 to 100,000 people were killed during witch-hunts. Among the executed were men too as accomplices of witches and sorcerers, but that was not the norm.

Execute all people in the Netherlands

The Spanish Inquisition started in 1478 and lasted until the nineteenth century. This Inquisition spread to other countries, including Portugal, parts of modern day Italy, and the Netherlands. The Inquisition of the Netherlands was established by King Charles V of Spain and continued to work with particular diligence during the reign of his son Philip II, who was a strong advocate of Catholicism. In addition to Spain, Philip II inherited from his father the Netherlands, Naples, Milan, Sicily, and some lands of the New World. To eradicate heresy in his domain, Philip strengthened the courts, and supported them with the use of spies and torture.

During the reign of Charles V, the people of the Netherlands were largely Catholic. But with the beginning of the rule of King Philip II of Spain, the Protestant Lutherans and Calvinists were becoming more important, which intensified the carrying out of the the Inquisition.

Many inhabitants of the Netherlands did not recognize Philip as their king due to religious reasons, excessive taxes, and the harassment of wealthy merchants. This discontent went from riots and escalated into a large-scale popular uprising in the 1560s. Then Philip sent one of his best military leaders, General Alba, to be the Governor of the Netherlands. With the arrival of Alba and his troops, the fires of the Inquisition broke out: just bad words were enough to send a person to death.

On February 16, 1568, the entire population of the Netherlands - at that time it was three million people - was sentenced to death, apart from a few exceptions.

On this day, Philip II presented a special memorandum, which stated that "except a select list of names, all residents of the Netherlands were heretics, distributors of heresy, and therefore were traitors to the whole state." The Court of the Inquisition adopted this proposal, and shortly after, Philip confirmed the decision with a document in which he ordered it to be carried out immediately and without concessions.

Philip II ordered Alba to proceed with the execution of the sentence. Mass executions began in the country, leading many nobles to flee to the German lands. Alba wrote back to Philip that he had already made a list of the first 800 people who would be executed, hanged, and burned after Holy Week. Hundreds of people were subjected to terrible torture before death: men were burned at the stake, and women were buried alive.

According to historians, during his six-year tenure in the Netherlands, Alba personally ordered the execution of 18,600 sentences. But over time, the resistance in the Netherlands was put down, and the Inquisition took on a weaker form.

The end of the Inquisition

The Inquisition was practiced in different European countries – and European territories outside of Europe, particularly the Spanish Empire - with different levels of intensity from the twelfth to the nineteenth centuries. It was often a time of cruel torture, bloody punishment, searches, suspicions, and accusations by the Catholic Church against heretics. And it was only by the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries that the religious investigative apparatus of the Inquisition was reorganized, and ultimately wholly abolished.

Spain abolished the Inquisition only in 1834. But the decline of the church court system began earlier, with the ascension to the throne of King Charles IV of Spain in the late eighteenth century. A changing domestic situation and ideas from other countries affected Spain, as the ideas of the French Revolution and enlightenment started to become more important.

All over Europe the times had changed and the Inquisition was over.

This article was brought to you by Jessica Vainer, writer of AU Edusson, an Australia-based writing service.

Editor’s note: That external link is not affiliated in any way with this website. Please see the link here for more information about external links.

References

https://www.britannica.com/topic/inquisition

https://www.catholic.com/tract/the-inquisition

https://readofcopy.com/lib/contemporary-narrative-proceedings-against-dame.pdf?web=api.tourtan.io

http://departments.kings.edu/womens_history/witch/wtimlin.html

https://dutchreview.com/culture/society/calvinism-netherlands-dutch-calvinist-nature/

http://www.reformation.org/heroic-holland.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Witch-hunt