By the time representatives of over thirty nations met at the French spa town of Evian in 1938 to discuss the plight of 700,000 Jews seeking places of refuge from Nazi controlled Germany and Austria, it was clear that their situation required urgent action. Despite many words of sympathy, there was very little practical assistance offered[i].

For Zionists, Palestine was the only credible option both for historic reasons and as a legitimate aim based on the approval at the San Remo Conference in 1920 which approved that ‘Palestine be reconstituted as the national home of the Jewish people’[ii]. However, as a result of subsequent Arab hostility to the idea, the British authorities had already introduced restrictions on Jewish immigration at a time when a refuge was needed more than ever.

Three years before the Evian conference, a meeting took place at the Russell Hotel in London to officially launch the Freeland League[iii], which had the aim of securing locations across the globe where large-scale immigration of Jews could be facilitated.

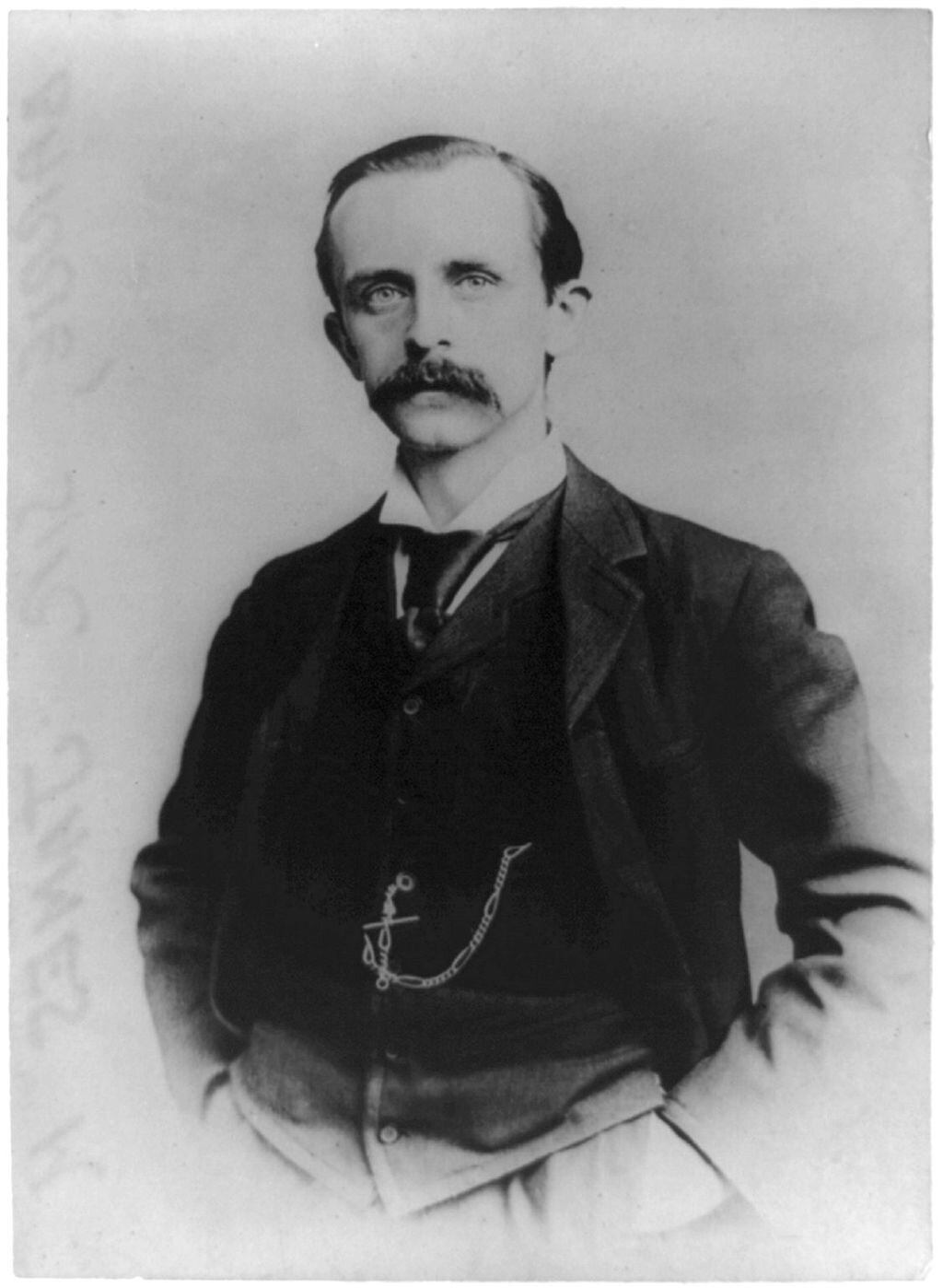

It was not the first organization of its kind. Almost thirty years earlier, the Jewish Territorialist Organization (abbreviated as ITO[iv]) had also been formed in London under the leadership of the playwright and novelist, Israel Zangwill. The ITO had sought out locations for large-scale settlement in the wake of pogroms once again in Russia and parts of Eastern Europe.

Despite intense diplomatic activity with representatives of several countries, all efforts failed and after the Balfour Declaration of 1917 supporting the creation of a Jewish homeland in Palestine, and the subsequent San Remo agreement three years later, the ITO went into something of a decline and finally lapsed following the death of Zangwill in 1926.

The Kimberley plan

The league’s most charismatic member was Isaac Nathan Steinberg (1888-1957), a Russian born Jewish social revolutionary who had served in the Bolshevik government under Lenin but was now in exile in London after disagreements with the regime.

Although an internationalist, Steinberg recognized the particular danger facing European Jewry and through his energy the league became organized, visible and increasingly vocal in seeking out support for refuges. He opposed the idea of a politically independent Jewish state which he considered was already no longer attainable in Palestine and would never be unacceptable to any government being asked to allow the creation of a state within a state.

The four requirements of finding at least one suitable location were that the land should be under populated; capable of sustaining a program of organized large-scale immigration; the area would be autonomous but there would be no political separatism; and finally, the project should not require any funds from the host government.

A series of reports and articles appeared between 1934 and 1938 promoting the desirability of large-scale immigration into the vast area of the Kimberley in north-west Australia[v]. A letter was published in the London Jewish Chronicle in which the author, Charles Chomley called on the Australian government to view an influx of Jews as being of a mutual interest[vi].

Given the backdrop of the failed Evian Conference, it must have seemed to the Freeland League that a genuine alternative had appeared. Australia, a country built by immigrants was assessed as an ideal proposition with its areas of under population, vast land mass and an acknowledged need for economic growth through a substantial increase in population. The continent was seen by the League as an opportunity to be pursued with some haste and Steinberg, a supreme public speaker and organizer was tasked with the role of leading the initiative.

An outline submission was made to the Australian High Commissioner in London suggesting that a joint scheme funded by the League would unleash the economic potential which had so far not materialized to the extent envisaged. The outcome was an invitation from the Commissioner for the League to prepare a blueprint setting out its vision supported by practical plans to turn it into a reality, and a favored area of land was quickly identified as the preferred location.

For some years, the focus of the government of Western Australia (WA) had been keen on attracting settlers from Britain, but the land which accounted for approximately one third of the entire continent, had seen few making their way to the Kimberley region located in the northern most area of the state. Without a substantial increase in population the area could not become economically developed to what was believed to be its full potential.

Making the case

Steinberg determined to find sponsors among influential members of British society, particularly but not only among the Labour Party movement where Ernest Bevin and Clement Atlee provided letters of reference for Steinberg. Similarly from the other side of the political stage, letters of introduction were sent by Conservative MPs, Leo Amery and Victor Cazalet to Australia’s new Premier Robert Menzies. In addition, the Anglican Church provided support resulting in the Bishop of Chichester writing to the Archbishops of Sydney and Perth asking each of them to give the League’s proposal a sympathetic hearing.

These and other actions were important preliminary foundations which would facilitate opportunities for Steinberg to meet leaders in WA and across Australia. In May 1939, he arrived in Perth, less than four months before the Nazi invasion of Poland and the start of war in Europe. Steinberg immediately set about what became an incredible almost single handed diplomatic offensive to secure support for the league’s project. What followed was a frenetic schedule which included eliciting support from leaders of the Perth community, an arduous journey to the Kimberley and upon returning, preparing and successfully presenting a report to WA Premier John Collings Willcock.

Connor, Doherty and Durack Limited, leased seven million acres of land in the eastern Kimberley and within days of his arrival, Steinberg met with Michael Durack who represented the company and found him supportive of a disposal to the League. Whether Durack and his partners saw this solely as a commercial opportunity or as a means of assisting Jews seeking a refuge, or both, is not clear but Steinberg was encouraged by this opportunity.

Rather than accepting Durack’s suggestion that they set forth immediately on a two thousand mile journey to the Kimberley, Steinberg decided his priority should be to build and strengthen support for the scheme among government, business, church and the labor movement and gain as much publicity as possible as a way of preparing the way for his eventual journey north.

He was soon engaged on his diplomatic strategy and received an invitation to a reception where the WA Premier was also on the guest list. Two days later they were meeting in the office of the Premier where Steinberg promoted the financial benefits which the scheme would bring to the state. Crucially, he also gave an assurance that the project would not require government funding, as the settlement would focus on becoming self-reliant and sustainable.

Willcock announced that he would remain neutral on the issue for the time being and advised Steinberg to thoroughly investigate the area and if it met with his expectation, to bring back a clear set of proposals for further consideration.

Visiting the Kimberley

Steinberg remained in Perth to continue his diplomatic offensive and met trade union and church representatives including Archbishop Henry Le Fanu. The cleric became so convinced about the scheme that he quickly arranged further meetings with other church leaders.

Next on Steinberg’s list were the media. Herbert Lambert, the editor of the West Australian newspaper, soon converted from a recently held position of decrying the very idea of a Jewish colony in WA, to becoming a leading voice in promoting the cause of the Freeland League.

In early June, after a flying from Perth to the port of Wyndham, Steinberg was surveying the landscape before him which he hoped would provide both shelter and a future for 70,000 Jews. He was accompanied by Durack and George Melville, an agricultural scientist who already had experience of investigating the potential for pastoral opportunities.

They spent the next three weeks motoring over 700 miles which was still a relatively small part of the Kimberley, but according to Steinberg covered the most important part of the region[vii].

Steinberg was impressed with what he saw and a vision emerged of Wyndham, the small coastal town becoming the gateway for new markets developed amid a mix of cattle and sheep farming alongside crops benefiting from the rich fertile soil, all benefiting from modern agricultural and management techniques. The availability of a plentiful water supply drawn from the Ord and Victoria Rivers would ensure the colony’s sustainability[viii].

Back to Perth

Upon their return to Perth, Steinberg and Melville began work on an extensive evaluation of the Kimberley’s potential for large scale development.

Reporting back to Premier Willcock, Steinberg again sought to reassure the Premier that the League would ensure the finance necessary to set up the colony was provided without recourse to either the WA treasury or Canberra which would have the ultimate say in whether the scheme could proceed.

The economic expansion of the colony would also reduce the state’s vulnerability of over reliance on imports. By contrast the opportunities for major exports to the Asian markets could provide sources for employment and revenue for the exchequer.

In terms of the specifically Jewish dimension, Steinberg viewed it as a colony but only in as much as it would provide a secure environment for promoting and sharing learning including the Yiddish language. However, he also made clear that the laws of Australia would be the laws of the colony and English would be the official language. This would not be a ‘state within a state’ which Steinberg knew to be unacceptable to both State and Federal governments.

Steinberg also recognized the fears often raised by critics of colonization schemes in general that once they had arrived, some settlers would seek their future in other parts of the state and even the wider continent. He was keen to address any such concern that Willcock might have and again gave an undertaking that the intention was to prevent this by building a self-sufficient and successful economic community.

The scheme would involve the League taking over a lease on the land area to be finally agreed for an initial three years and upon its expiry, a new lease of ninety-nine years would be granted.

In addition to securing the support of the Premier, Steinberg was also able to address the state parliament and by early September less than four months since his arrival in Australia, various newspapers were reporting that the WA government was backing the scheme, subject to the approval of the Federal government in Canberra[ix].

Support was also secured from the Perth Chamber of Commerce as well as the labor organizations, and a petition was issued which included members of the clergy, authors, and academics.

Not everyone saw the scheme in such a positive light. The idea of group immigration on the basis of colonization had never previously been part of Australian policy. Some critics did not accept that the League could prevent onward migration, after all the land both within the proposed territory and outside of it was still Australia.

World War Two

However, time was already moving against the scheme. Almost at the same point when Steinberg seemed to be conquering all before him, the Nazi invasion of Poland resulting in the declaration of war by Britain, France and the Commonwealth nations brought a new focus and changed priorities.

Steinberg and the many supporters of the League’s proposal continued to promote the scheme and in August 1940, a memorandum was submitted by the League to the Prime Minister, Robert Menzies in Canberra.

Early in 1940, at the invitation of individuals aware of the Kimberley proposal and sympathetic to the idea of Jewish settlement, Steinberg was in Tasmania and exploring the potential for a similar project. Ultimately the scheme did not materialize and is both an interesting but rather tragic story in itself. However, it also shows that he was still open to considering any location which offered the potential for the aims of the League to be achieved and also the tremendous energy he devoted to the cause.

Although the urgent war effort had delayed any response until the following year, the Federal government announced that the matter had been deferred[x]. Officially the opportunity remained on the table and even by November 1941, letters of support were being reissued and restated[xi]. Nevertheless, the momentum built up by Steinberg during those few months of 1939 was never again to be repeated.

Later that year, Australia faced a new enemy to the north as Japan entered the war siding with the Axis Powers in Europe and the urgency to focus on defending Australia, as well as continuing the Allied campaign for victory inevitably became the overriding objective.

Decision

Three years after the letter announcing the decision to defer consideration of the memorandum, Steinberg received a letter from the Prime Minister, John Curtin announcing that the Government could not entertain ‘group settlement of the exclusive type contemplated by the Freeland League’[xii]. Understandably, the war effort took center stage for the Australian government, but perhaps it was the very nature of the proposed settlement which finally ended any meaningful hope of it becoming a reality.

Despite gaining support from many influential individuals and organizations, including some for whom the primary focus was the purported economic benefits to the Australian economy, the likelihood that the scheme would ever have become a reality remains little more than intriguing speculation.

For all the public support gained for the Kimberley project, the league had never envisaged accepting more than tens of thousands of German and Austrian Jews, but as Steinberg wrote: ‘let a small part of them at least have peace for a few generations’[xiii]. Even that was not to be.

Notwithstanding the ultimate conclusion of the scheme, Steinberg’s efforts should be recognized for the incredible speed of his success in gaining widespread support, particularly during those frenetic months of diplomatic activity following his arrival on that continent in May 1939.

Perhaps the most appropriate description of that time is encompassed in the words of Chaim Weizmann, who subsequently became the first President of Israel, when he wrote: ‘The world seemed to be divided into two parts – those places where Jews could not live and those where they could not enter’[xiv].

Now, you can read William’s article about the man who proposed a Jewish State in the 19th century here.

Finally, what do you think of the Kimberley Scheme? Let us know below.

[i] The exception was an offer by the Dominican Republic to accept 100,000 Jewish refugees. In the event, less than 1000 arrived and there has been much speculation about the motivation for the offer (see: Metz A. Why Sousa? Trujillo’s Motives for Jewish Refugee Settlement in the Dominican Republic. University of Illinois).

[ii] Besacenter.org. Mideast security and policy studies paper #172. The Conference signed the Treaty of Sevres which gave international recognition to a Jewish homeland in Palestine.

[iii] The full name was The Freeland League for Jewish Territorial Colonisation.

[iv] From the Yiddish name – Yidishe (Idishe) Territoryalistishe Organizatsye.

[v] Australian Quarterly. 1934. The article was written by a vice-chancellor. University of Melbourne.

[vi] Jewish Chronicle. May 1938

[vii] Steinberg I N. Australia: The Unpromised Land. Gollancz. 1948

[viii] Gettler L. An Unpromised Land: The Plan for a Refugee Haven in Australia’s North-west. 2019

[ix] Jewish Telegraphic Agency. 30th August 1939 and Herald (Melbourne). 1st September 1939

[x] Steinberg. ibid

[xi] Steinberg. ibid

[xii] Steinberg. ibid

[xiii] Steinberg. ibid

[xiv] Manchester Guardian. Settlement of Refugees. May 1936.