Whether the pun in the title made you laugh or cringe, it is fitting for the event that this article is about, the Battle of Cannae—indeed an uncanny defeat. Here, Nathan Richardson explains what happened in the 216BC battle between the Roman Republic and Carthage, part of the Second Punic War.

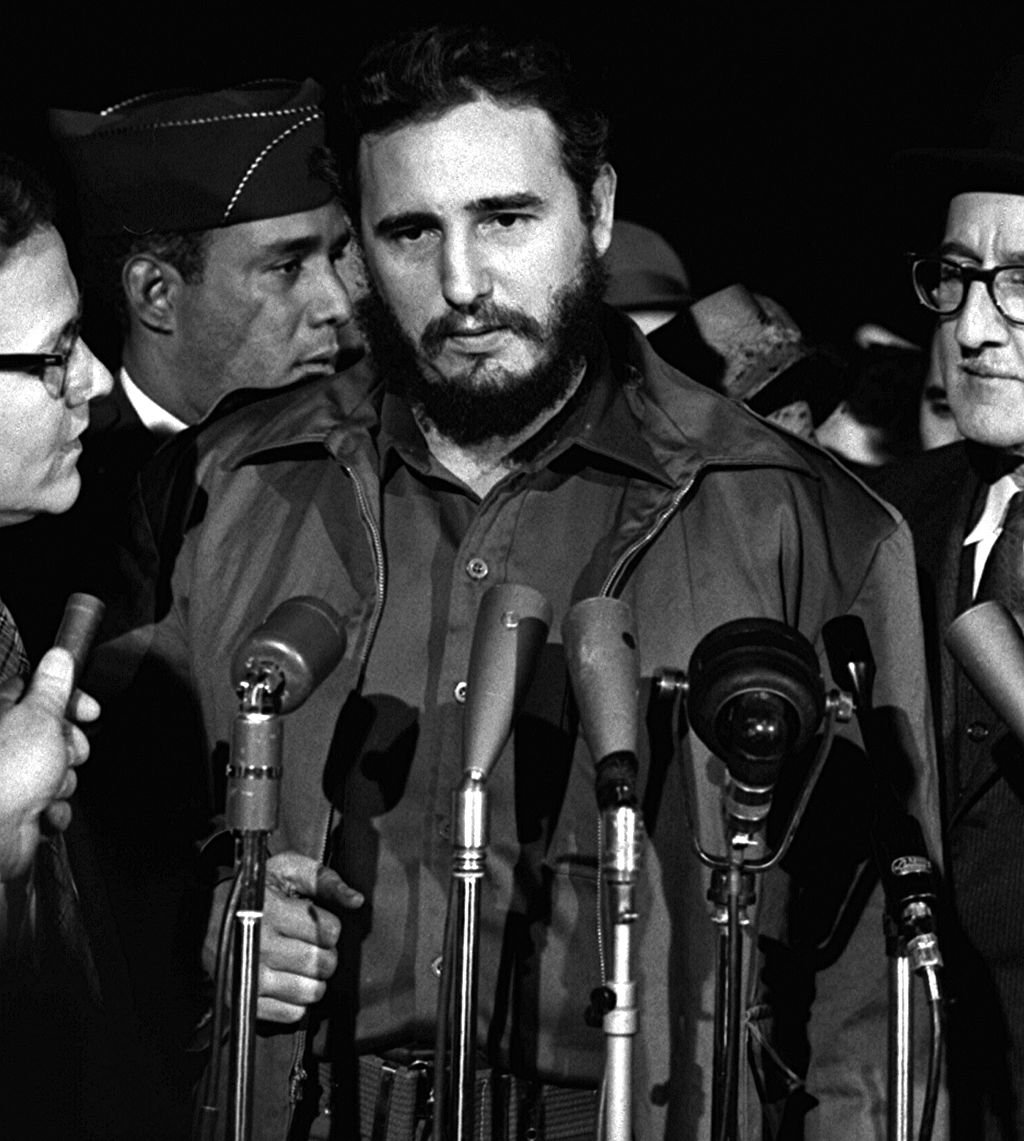

The Death of Aemilius Paulus at the Battle of Cannae. A 1773 painting by John Trumbull.

In 216 BC, the Roman Republic faced not only defeat, but the possible dissolution of their empire. The foreign armies of Carthage, Rome’s rival from across the Mediterranean on the North African coast, tread on Italian soil. Hannibal Barca, one of history’s most renowned and daring generals, and Carthage’s best hope of victory, cowed Rome’s allies and threatened Rome herself. Having traveled from the Iberian Peninsula, through southern Gaul (modern-day France), across the nearly-impassable Alps, and down into Italy, Hannibal rampaged into the very heart of the burgeoning empire of Rome. Hannibal smashed three Roman armies in quick succession: the Battles of Ticinus (in 218 BC) Trebia (also in 218) and Trasimene (in 217) (Goldsworthy, 22-27). The Carthaginian general, whose father had reportedly made him swear eternal enmity for Rome, seemed undefeatable (Goldsworthy, 15). Each battle the Romans fought brought them closer to complete destruction. Each time the Roman army faced the Carthaginians in the open field, Rome’s vital manpower was further depleted. Each defeat, additionally, began to erode the various Italian cities’ confidence in Rome to defend them. In the north of Italy in the Po River Valley, many recently-conquered Gauls living there flocked to Hannibal’s side and threw off the Roman yoke (Keppie, 25-6). Rome stood determined still, yet the question remained whether Roman resilience would outlast Hannibal. Rome buckled under these crushing defeats, yet far darker days lay ahead.

Fabius’ Plan

In response to this crisis, the Romans elected a dictator to see them through the trials ahead—a man named Quintus Fabius Maximus Verrucosus (in the future, simply Fabius). Fabius realized that Hannibal would likely defeat the next hastily-prepared Roman army just like the last three. He saw no point in throwing another army of untested Romans against Hannibal’s experienced and hardy mercenaries and allies. Therefore, Fabius resolved to keep his army in being, and carefully avoided pitched battles with Hannibal—all the while shadowing the Carthaginians and attempting to disrupt their supplies. Hannibal, no doubt, preferred to annihilate one hastily-assembled and ill-trained set of legions at a time—until Rome was forced to sue for peace. Yet Fabius did his best to not do Hannibal the service of fighting him in the open. If Fabius could keep this up, he would slowly deprive Hannibal of food and wear down his multi-ethnic army (Goldsworthy, 27-32). Hannibal, after all, was quite vulnerable. He was an invader in a foreign land, and many of his men would only fight so long as they were paid and taken care of (Goldsworthy, 46). If the Romans haunted Hannibal’s steps, kept him from properly resupplying, and provided Hannibal’s men no source of spoils, their morale would eventually decline, and Hannibal could possibly be destroyed or driven out of Italy.

However, the Roman people soon began to tire of Fabius’ strategy, interpreting them as hesitancy or even cowardice. Cunctator (“the Delayer”) was the moniker the people soon gave him (Keppie, 26). According to the Greek historian Plutarch, Hannibal, aware of Fabius’ unpopular strategy of non-engagement, purposed to further discredit Fabius. To do so, he sacked and burned the lands surrounding Fabius’ personal holdings, yet left Fabius’ property untouched—going so far as to post guards around Fabius’ property to ensure it stay unmolested. When word of this reached Rome, Fabius’ reputation took a serious downturn, and slanderous rumors of treason circulated around Rome (Plutarch, 217). Once his six-month term as dictator expired, Fabius left the army and returned to Rome (Goldsworthy, 31). Not only did Fabius leave office deeply unpopular, but his strategies would be disregarded by his successors.

With the dictator out of power, Rome again appointed two Consuls to lead her through this crisis. These two Consuls were Paullus and Varro. Responding to the impatient voices of Rome, the two Consuls hastily raised a new army, this time made of eight legions and troops from various allies of Rome (probably in the form of light infantry and cavalry), and set forth to meet Hannibal. This army that Paullus and Varro led was indeed massive, numbering around 75,000 men. Their army outnumbered Hannibal’s force nicely, which numbered only 40,000 men (Keppie, 26). If all else were equal, an army with such a numerical advantage must surely win a pitched battle. However, Hannibal’s skill as a tactician, as well as the Roman consuls’ poor decisions, would hobble Rome in taking full advantage of her superior numbers. Additionally, Rome’s hastily formed force, man for man, was far from the Carthaginian’s army’s equal.

The Battle

The Romans and the Carthaginians met by the Aufidus River (now called the Ofanto) near the town of Cannae in southeast Italy. The ground chosen by the Romans favored the Roman situation, since the Aufidus running on the Roman right and rough land on Roman left limited the space open on either flank for Carthaginian cavalry (which was superior to the Roman’s) (Goldsworthy, 99). Additionally, the ground offering little room for maneuver complemented the Roman tactics for this battle. Their plan was blunt: they would launch a full-frontal assault and attempt to use their enormous numbers to brute-force their way through the Carthaginian line. However inelegant it might be, the plan’s lack of complexity did not ask too much of the poorly trained and hastily organized army the Roman’s fielded (Goldsworthy, 113-16).

Between the two Consuls, Varro is typically depicted as the braggart fool who bumbled his way into Hannibal’s trap, and Paullus as the martyred prudent commander. Though it is difficult not to blame the day’s commander for the calamity about to befall the Roman army, especially since Varro was most certainly the bolder of the two commanders, this characterization is likely an exaggeration at least (Goldsworthy, 84, 72-3). However, it must be remembered that neither consul had ever commanded such a massive force (this was one of the largest armies Rome would ever put into the field), and both consuls were entirely outmatched by Hannibal in generalship (Goldsworthy, 66, 64).

Hannibal’s arrangement of troops was key to the Carthaginian success. Contrary to the Roman’s expectations (and possibly good sense), he placed his least experienced and least reliable troops (the Celtiberians from modern-day Spain) as his center in the battle lines. He also arrayed these troops in an arc, bowing out towards the Roman lines. These troops provided a very tempting focal point for the Roman charge. So, with a deliberately weak center, Hannibal posted his best troops, his Libyan heavy infantry, on either flank (Keppie, 26). On each far flank, both sides posted cavalry on either side. Though vastly outnumbered in terms of infantry, Hannibal did possess more cavalry and of higher quality than the Romans mustered. This equestrian superiority would become another key element of Hannibal’s victory (Keppie, 26).

In typical ancient warfare form, the battle commenced with light infantry of both sides armed with javelins, bows, or slings running forward and attempting to break up the enemy’s formations with projectiles. The light infantry also served another purpose: they helped to screen the movements of the main army from the enemy’s view. If the Roman commanders had been able to see Hannibal’s arrangement of troops, they may have realized what kind of trap lay in store for them. Thus, light infantry assisted in blinding the commanders on either side from having a complete picture of their enemy’s designs (Keppie, 26). Further, Plutarch states that a strong wind blew sand into the eyes of the Romans during the battle, giving the Carthaginians a further edge over the Romans (Plutarch, 223).

Trap

Paullus’ and Varro’s army blundered forward, intent on smashing through the weak Carthaginian center. While this drama played out in the center, the Roman and Carthaginian cavalry engaged in a heated melee on the flanks. The cavalry situation was less in Rome’s favor. On the Roman right, Hannibal’s allied Celtic cavalry beat the Roman cavalry on that side, and forced the Romans to flee. Meanwhile, on the Roman left, the Roman cavalry managed to hold off Hannibal’s Numidian cavalry. But the Roman left soon broke and fled when the victorious Celtic cavalry, abandoning their pursuit of the Roman right’s horsemen, turned against the Roman left’s cavalry (Keppie, 26). Thus, the Roman cavalry on either flank were beaten and driven off, leaving the Carthaginian cavalry unopposed.

While the Roman cavalry fought and fled the field, the Roman infantry, though still superior in numbers, pushed themselves further and further into Hannibal’s trap. As the Romans pressed forward, Hannibal’s center fell back and began to break, inverting the arc that the Carthaginian line formed. However, this arc did not break. Instead, the formerly concave arc turned convex. Every step forward the Roman center made was one step farther into Hannibal’s trap. As Hannibal’s center fell back with the Roman push, the Libyan infantry, on the extreme ends of the line, began wrapping like tentacles around the Roman flanks, eventually transforming the orderly host of Roman infantry into a disorganized mass of men, where all semblance of formation disappeared, and the enemy were suddenly present on three sides—Celtiberians in the front and Libyans on either flank (Keppie, 26).

The Roman Legions’ fate was sealed with Hannibal’s final move: the victorious Carthaginian cavalry charged the Roman rear. With just-victorious Carthaginian cavalry nipping at their heals, the Roman infantry in the rear began to melt away. The poor Romans in the very front did not flee—they could not. The veteran Carthaginian infantry bore down on them, and a massive noose, encompassing tens of thousands of Romans, began to tighten. They were pushed into a tighter and tighter mass, so much so that the legionnaires could not properly use their weapons. Many men were forced to stand and wait for all the men in front of them to be hacked down before they met their own end (Goldsworthy, 177). Only about 10,000 managed to escape the slaughter and limp dejectedly back to Rome. The rest, over 50,000 Romans, were slaughtered where they stood or as they fled (Goldsworthy, 183). Among the lucky survivors was Varro, the impatient Consul who fell for Hannibal’s trap so nicely. Paullus, on the other hand, died with his men.

Aftermath of Defeat

The defeat Rome suffered at Cannae was colossal. A large proportion of Rome’s men of fighting age had been slaughtered. A defeat such as Cannae would have been the end for almost any other empire. Yet, Rome was not like other empires. Rome did not sue for peace. A galvanized Senate and People of Rome were more determined than ever to rid Italy of Hannibal and the world of the hated Carthage (Goldsworthy, 197). New armies were raised, and the Fabian strategies resumed (Keppie, 28). Hannibal, having doubtlessly suffered heavy casualties at Cannae (though light compared to the Romans), did not follow up his victory with a march on Rome, against the advice of his more aggressive generals. One of his generals is recorded by Livy as having told the great Hannibal, “Truly the gods do not give everything to the same man: you know how to win a victory, Hannibal, but you do not know how to use one” (Goldsworthy, 189). Instead, Hannibal focused on trying to turn more Italian cities (allies of Rome) to his side in order to get the men and supplies he needed. Though many flocked to his banner after Cannae (notably, Italy’s second-largest city, Capua), not enough of them did. Rome still held firm, and so would many of Rome’s allies (Keppie, 28). The war continued in Italy for over a decade more. In 204 BC the famed Roman general Scipio Africanus made an invasion of North Africa from Sicily, with the intent of assaulting the city of Carthage itself. He was not known as Africanus then, but his upcoming campaign in North Africa would soon earn him that title. In response to this threat, Hannibal was recalled from Italy to defend the seat of the Carthaginian empire (Goldsworthy, 202). In total, Hannibal and his army had ravaged Italy for nearly fifteen years—fifteen years of brutal, bloody conflict across many battlefields. Yet, Cannae would be the one battle that Rome remembered the clearest as one of their darkest days—though a dark day that was not the end of Rome.

Influence of Cannae

Hannibal executed a near-perfect encirclement of eight Roman Legions by the Aufidus River in southeast Italy. In awe of this achievement, generals throughout history have attempted to replicate it. The “double-envelopment”, “Pincer movement”, or simply “encirclement” became the dream of every ambitious general. German General von Schlieffen planned (unsuccessfully, as it would turn out) to achieve a double-envelopment of the Allied forces in the First World War. So too did US General Schwarzkopf in the Gulf War. Hannibal’s double-envelopment was and is the ultimate winning-stroke that many commanders throughout history have sought for, yet rarely achieved. Many generals throughout history have looked all the way back, over two thousand years ago, to the Battle of Cannae for inspiration (Goldsworthy, 205-6).

What do you think of the Battle of Cannae? Let us know below.