Confederate Supply Network

The Confederate Army invaded the north despite facing severe resource limitations. The Confederacy struggled with manpower shortages, supply line constraints, and limited access to industrial and transportation infrastructure. These limitations made it challenging for Lee to fully address and overcome intelligence and logistical issues during his planning process. Lee recognized the limitations in terms of supplies, extended supply lines, and the difficulties of operating in unfamiliar territory. Lee and his staff understood that their army would have to rely on a lengthy and vulnerable supply line stretching back to Virginia, which could be impacted by weather, terrain, enemy interference, and the strain of transporting essential provisions and ammunition. Despite these challenges, Lee decided to proceed with the campaign. In retrospect, it is apparent that these logistical challenges had a significant impact on the Confederate Army's effectiveness and ability to sustain their operations during the campaign.

Several potential strategies and actions could have been considered to alleviate problems that could have been expected. Lee could have made efforts to shorten and secure his supply lines. Lee could have used several additional resources history shows that he didn’t have in planning his invasion in June 1863:

Spies on the ground to reconnoiter

Cavalry in his front and sides to know where the enemy was.

Pontoons over the Potomac that he could get across in an emergency.

Sufficient long range artillery ammunition to sustain multiple attacks in a long offensive campaign.

A functioning supply line to move captured goods retrograde to any advance.

Improved command and control, with sufficient staff to maintain communications with corps leaders at all times.

With Stonewall Jackson’s death at Chancellorsville, Lee had two new corps commanders. The Confederate Army's command structure was dispersed, with multiple corps and divisions operating somewhat independently. This fragmentation made it challenging to consolidate and synthesize information from various sources and hindered the efficient gathering and analysis of intelligence.

Intelligence Flaws

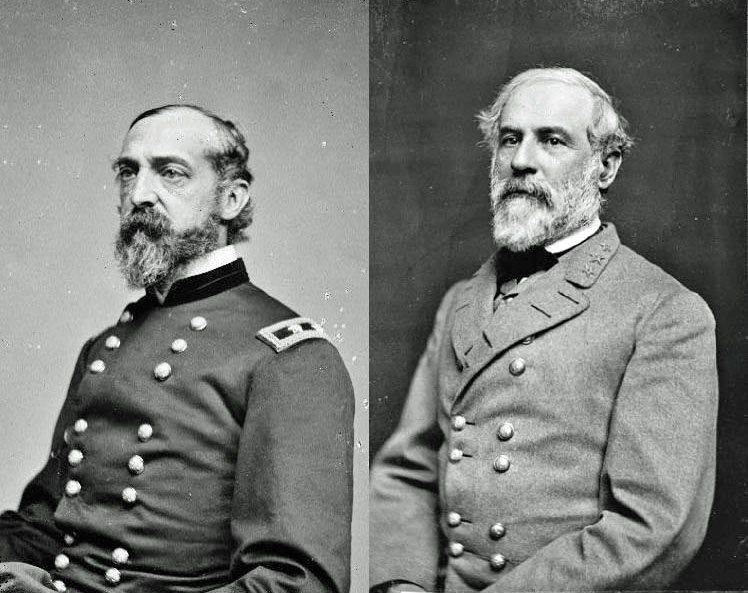

General Lee faced challenges in obtaining accurate and timely intelligence regarding the location and movements of Major General Joseph Hooker and the Army of the Potomac. The lack of reliable intelligence about the enemy's positions and intentions affected Lee's decision-making and ability to plan his own movements effectively and placed Lee at a disadvantage. Confederate intelligence efforts were hampered by various factors including limited reconnaissance capabilities especially the absence of JEB Stuart. The combination of limited reconnaissance capabilities, dispersed command structure, Union defensive measures, communication limitations, and unfamiliar terrain contributed to the challenges faced by Lee in obtaining accurate intelligence about Hooker's army.

The ANV suffered from limited reconnaissance capabilities. The Confederate Army had limited cavalry resources for conducting reconnaissance and gathering information about the enemy. The cavalry, traditionally responsible for scouting, was stretched thin, and their ability to penetrate Union lines and gather reliable intelligence was hampered. Lee instructed Stuart to keep the Army of Northern Virginia informed of the movements and activities of the Union Army, maintain communication, and act as a screen to prevent the Union forces from gaining intelligence on Lee's own army. Lee's orders emphasized the importance of timely and accurate information. Allowing Stuart to circumnavigate the Union army rather than be his eyes and ears must rank among Lee’s greatest mistakes. Using what cavalry he had in guarding passes behind him was his second biggest mistake.

Lee had no formal intelligence service like General Sharpe and the Bureau of Military Intelligence of the Union army. The CSA had very few covert operatives in the north, as opposed to the south, where the citizens favored him. This is a bit surprising given the large number of KGC and Copperheads; but western Maryland and southern Pennsylvania were solid pro-Union, another factor Lee may have overlooked.

Operational Manifestations

The Confederate Army relied on a limited and overburdened transportation system to move men, equipment, and supplies. The lack of adequate railways and the reliance on horse-drawn wagons slowed down the movement of troops and hindered the delivery of essential provisions. Maintaining a constant supply of ammunition, weapons, and other necessary equipment was a challenge. The long supply lines made it difficult to ensure a steady flow of these vital resources to the troops on the front lines.

The Union used railroads and rivers to transport their supplies. But where Lee wanted to go strategically, behind the Blue Ridge Mountains to screen his movement, there was no railroad and no river. He had to move everything over land. So Lee employed a wagon train. Consequently, Lee had a 125-mile route for supplies to traverse to get to Gettysburg and more to Harrisburg. The massive wagon trains limited Lee’s ability to maneuver and to bring troops from the rear in case of an unexpected need, as happened on July 1. Moreover, the priority he placed on protecting them required the remaining cavalry units after Stuart left, leaving him without the necessary reconnaissance.

Either 4 horses or 6 mules pulled the supply wagons. They could carry 2000-2500 pounds but moved only at marching pace, about 3 miles per hour, and less if the roads were muddy or rocky. Lined up on a road, each wagon took up 60 feet of linear space. Lee’s trains stretched for dozens of miles. Infantry and artillery had to use the same roads as the wagons, resulting in traffic jams and delays. The administration of the order of march to prevent pile-ups at crossroads was labor intensive.

Wagon trains moved at a relatively slow pace compared to other means of transportation, such as railways. This hindered the army's ability to swiftly maneuver and respond to changing circumstances on the battlefield. Long wagon trains stretched over a significant distance and were vulnerable to attacks from enemy forces. Union cavalry units often targeted these trains, aiming to disrupt supply lines and inflict damage on the Confederates. Wagon trains had a limited capacity, both in terms of the amount of supplies they could carry and the number of troops they could transport. This constrained the amount of provisions and equipment that could be transported to the front lines, potentially leading to shortages.

Animals need to be cared for, fed, and rested, which added to the logistical burden and increased the strain on resources. The animals themselves required massive forage. Mules needed 9 pounds of grain 10 of fodder and 12 gallons of water daily; horses needed 14 pounds, 14 pounds and 10 gallons respectively. They needed horseshoes, and men to apply them. The waste disposal problem is mind- boggling: every day, a single animal produced 10 pounds of manure and 2 gallons of urine. Unless animals are optimally cared for, they can’t burden the loads; they move more slowly and carry less until they break down and the army is immobile.

Wagons, like all vehicles, required regular maintenance and repairs. This included fixing damaged wagons, replacing worn-out wheels, and addressing other mechanical issues. Finding the necessary resources and skilled personnel for these tasks added to the logistical challenges.

Lined up on a road, each wagon took up 60 feet of linear space. Lee’s trains stretched for dozens of miles. Infantry and artillery had to use the same roads as the wagons, resulting in traffic jams and delays. The administration of the order of march to prevent pile ups at crossroads was labor intensive.

This was a logistics nightmare. It would directly impact when Longstreet would reach the field, what weapons and armaments would be available, coordination of the 3 corps in battle and of course, the ultimate retreat after the battle. And the fact is, Lee lost this critical battle for precisely these reasons. The logistical limitations faced by Lee's army had a significant impact on their arrival and readiness on the field at Gettysburg. Reliance on slow-moving wagon trains caused delays in the arrival of Lee's troops. The stretched supply lines and the need to coordinate the movements of dispersed units slowed their progress, affecting their timely arrival at the battlefield.

Battlefield Impact

The extended marches and inadequate provisions necessitating foraging combined with the strain of traffic jams and slow movement, took a toll on the Confederate soldiers. Many suffered from fatigue, diminishing their physical condition and overall readiness for battle. Additionally, some soldiers straggled or fell behind due to exhaustion or the inability to keep up with the army's pace. Many Confederate soldiers were sleep deprived and fatigued when they reached the battlefield after night and forced marches, diminishing their overall effectiveness.

July 1. Major General Henry Heth commanded a brigade under AP Hill. He is traditionally assigned blame for unintentionally commencing the Battle of Gettysburg. He did send half of his division toward the town; he later claimed that he was looking for supplies, including shoes. He apparently did not know that Early’s division had been through the village a few days previously, and any supplies were long gone. On June 30th he encountered mild resistance on the road but it was thought to be a volunteer militia, not regular army. This lack of intelligence would be the real reason the battle would start.

On the morning of July 1, Heth’s division marched down the Chambersburg Pike to perform a reconnaissance-in-force. At about 7:30 am 3 miles outside of town near the McPherson barn, the first shots of the battle were fired. The order of march was not the one a commander would choose if a battle was imminent. Pettigrew deployed his men without cavalry in front; there were no pickets and no vedettes and in fact the first enemy he ran into were Union vedettes. The front of the line was Pegram’s artillery, followed by Archer and Davis’ infantry brigades.

Lee's army was spread out over a significant distance due to the wide deployment of his troops during the march north, from south of Cashtown to Harrisburg. This dispersal made coordination and concentration of forces more challenging, impacting their ability to concentrate their strength. The splitting of the ANV during the march north meant piecemeal arrival of Confederate troops on the battlefield, which affected the initial coordination of Lee's forces. This resulted in a fragmented Confederate attack on the first day of the battle, as units arrived at different times and were not able to coordinate their efforts effectively. The arrival of troops at unplanned times and locations posed challenges to the reinforcement and maneuverability of troops, resulting in a hindering to exploit opportunities and limiting the flexibility of his response to Union movements. These issues were most apparent when General Ewell concluded that he lacked the resources (manpower and supplies) to attempt an attack on Culp’s Hill in the late afternoon.

July 2. Improved transportation and supply arrangements could have allowed General James Longstreet's troops to position themselves more swiftly on July 2. Improved communications would have facilitated better coordination between Longstreet and Ewell. Better communication with his division commanders could have expedited the movement of troops and improved the response to General Sickles’ unwise move to the Peach Orchard.

Adequate logistical support would have facilitated the swift movement of wagons and artillery pieces, enabling them to reach positions in a timelier manner. Had coordinated attacks been organized, the battles in the Wheatfield and Little Round Top might have gone differently.

More effective reconnaissance and intelligence operations would have provided Longstreet with timely and accurate information about the enemy's positions, enabling him to make more informed decisions regarding the deployment of his troops, especially the fact that Little Round Top was occupied by Union forces.

July 3. The supply problems and logistical challenges faced by the Confederate Army had significant repercussions for Pickett's Charge. The movement of the ANV away from its railroads to create a screen with the mountains also caused the loss of the capacity to replenish its long-range artillery ammunition. Recognizing the limited transportation capacity imposed by a wagon train, compromises were necessary regarding the amount of artillery ammunition that could move with the army. The long-range artillery necessary to support offensive action was different from the canister and grapeshot used in defensive battles. Since Lee had no idea what the nature of the battle would be, he brought some of each, but this proved to be insufficient. Lee did order delivery of additional artillery ammunition with the Ordinance department as he moved farther north, but it never arrived. Consequently, the Confederate forces were unable to provide adequate artillery support for Pickett's Charge. The lack of artillery firepower weakened the overall impact of the assault and increased the vulnerability of the advancing Confederates.

The Bormann fuses used by the Confederate Army during Pickett's Charge were also a significant issue that further exacerbated the challenges they faced. The fuses were designed to control the timing of the explosion of artillery shells, and their malfunction or improper functioning had detrimental effects. The origin of the logistical fuse problem was an explosion and fire at the Richmond arsenal on Brown’s Island on March 13, 1863. The explosion resulted temporarily in ordnance supplies originating from Selma and Charleston. These fuses were designed with a resin filler that made them explode about 1 second later than those manufactured in Richmond. This filler softened and mixed with the powder in humid warm weather such as that in the first days of July, causing longer burning fuses and non-detonating shells. These "new" fuses burned slightly slower than what the artillerists were accustomed to.

The CSA artillerymen had no forewarning that there was a difference in these fuses that would make them burn longer than a fuse of the same length coming out of Richmond.

Consequently, in many instances fuses malfunctioning or burning at an unpredictable rate were noted. This meant that some shells exploded too late, reducing their effectiveness and impacting the intended timing of the artillery barrage preceding the charge. The inferiority of the Bormann fuse combined with the intentional overhead trajectory led to the inefficiency of the artillery. If firing overhead and the fuse explosion is delayed by a second, it will not explode until it has gone past the target.

What do you think of the Challenges of the Army of Northern Virginia in the Gettysburg Campaign? Let us know below.

Now, if you missed it, read Lloyd’s piece on how the Confederacy funded its war effort here.