The French started to send prisoners to their colony in French Guiana in the nineteenth century. The penal colonies set up there are probably some of the worst ever. Harsh conditions, dangerous animals, little medical care, brutal guards, and backbreaking labor led many to die in them. And the system lasted well into the twentieth century. Robert Walsh explains…

‘The policy of the Administration is to kill, not to better or reclaim.’

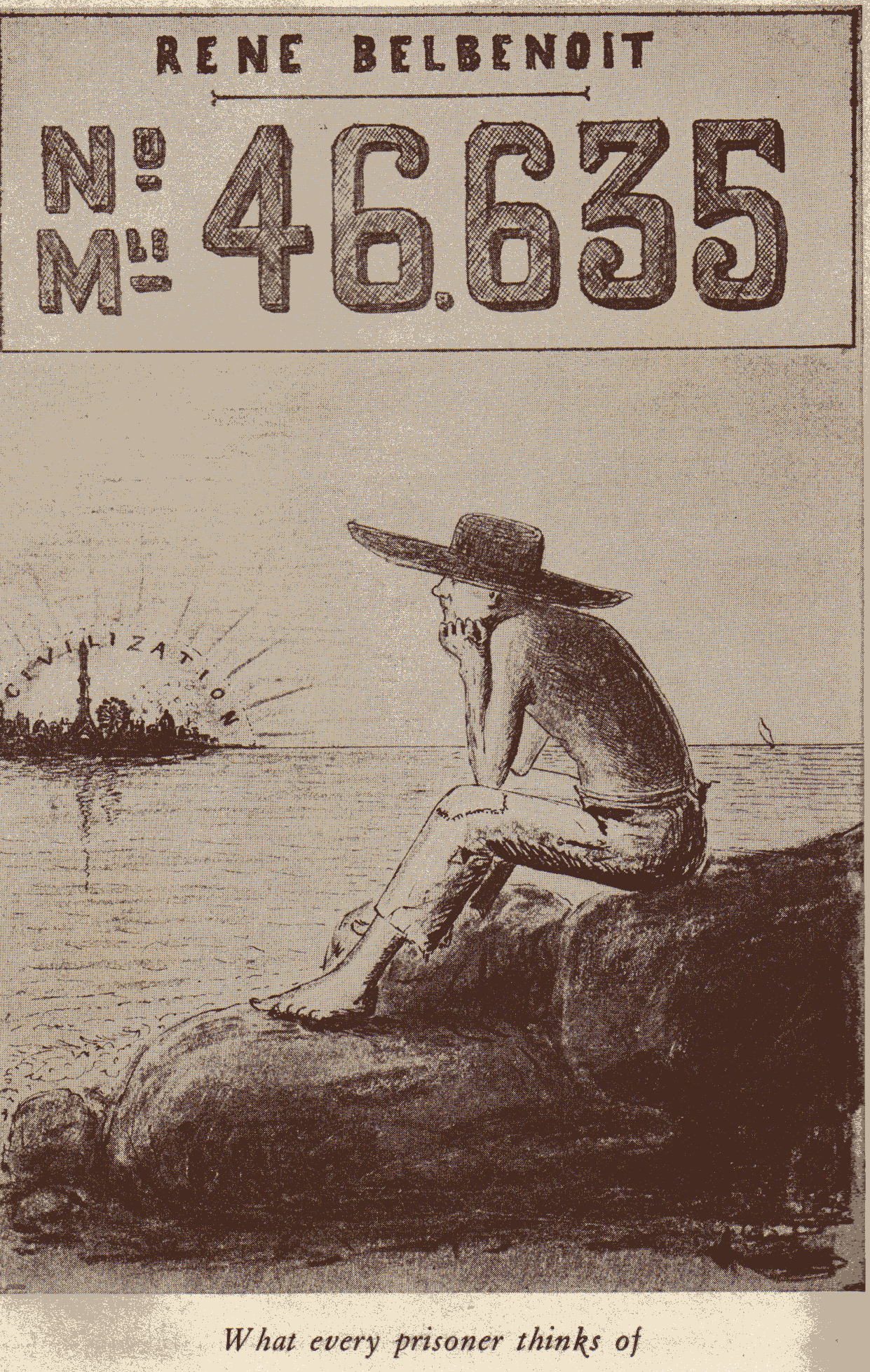

- Rene Belbenoit.

The typical inmate’s attitude in the colonies, from Rene Belbenoit’s Dry Guillotine.

It is 1852. In France, Emperor Napoleon III, increasingly worried by rising crime and insufficient colonists to consolidate France’s empire, devises a new, dreadful solution. Napoleon isn’t interested in social reform, he’s interested in social cleansing where criminals can simply be exported elsewhere and forced into servitude, preferably never to return. His brainchild will become the most infamous penal system in history. Even today it’s a taboo subject for many French people. His plan is for a system of penal colonies in French Guiana. Inmates call it ‘Le Bagne’. Former inmate and escaper Rene Belbenoit called it the ‘Dry Guillotine’ and his 1938 book damned both the colony and the ideas behind it. The wider world still calls it ‘Devil’s Island’.

Many people today think of the Guiana colonies in that way, three small islands off the Guiana coastline (Royale, St. Joseph and Devil’s). They weren’t. Out of approximately 70,000 inmates, only 50 were incarcerated on Devil’s Island. It was also reserved for French political prisoners, not conventional criminals. 70,000 inmates went out to Guiana, only 2,000 or so returned. Only around 5,000 survived to finish their sentences. The rest succumbed to disease, murder, execution, failed escape attempts and deadly animals populating the Guiana jungle. Conditions were so bad that between 40% and 80% of one year’s intake would be dead before the next year’s intake arrived.

The trip begins

Inmates were collected from all over France, confined pending transportation at St-Martin de Re near the port of La Rochelle. Twice a year an old steamer named ‘Martiniere’ left for Guiana. The inmates were escorted from the prison to the dock under military guard. Specially trained Senegalese colonial troops with fixed bayonets marched them through the town where their friends and families would have their last sight of ‘Les Bagnards’ as they left, mostly never to return. To quote its most famous inmate Henri ‘Papillon’ Charriere: “No prisoner, no warder, no gendarme, no person in the crowd disturbed that truly heart-rending moment when everyone knew that one thousand, eight hundred men were about to vanish from ordinary life forever.”

Their suffering began aboard ship. Crammed below decks like sardines with only a half-hour a day on deck for fresh air and sunlight, with hardly any hammocks leaving many inmates sleeping on steel decks, with any trouble below decks punished by the guards turning hot steam hoses on the inmates, life aboard ship was miserable. Guards could also flog inmates who disobeyed even insignificant orders. Inmates often murdered each other to settle grudges or robbed each other of whatever small possessions they had. Life in Guiana, for those who survived the three-week voyage, was immeasurably worse. All an inmate had to endure the voyage was issued prior to embarkation; a convict uniform, wooden clogs, a hat and a small secret device known to convicts as a ‘plan’ or ‘charger’. A ‘charger’ was a small metal tube carried internally, perhaps containing money, gems, small escape tools, a map and maybe a small knife for self-protection. If an inmate was discovered carrying one, or indeed broke any other rule aboard ship deemed too serious for a mere flogging, they spent the rest of the voyage shackled in the bilges in searing heat and deafening noise, directly over the engine room and boilers.

In St. Laurent

New arrivals landed at St. Laurent, capital of the Guiana penal system. At St. Laurent most inmates would serve their sentences unless they were interned on the islands or sent straight to jungle work camps. At St. Laurent they were classified according to security risk and criminal record. Standard inmates were ‘Transportes’, transportees who had committed more serious crimes. Lower down were ‘Relegues,’ serial petty offenders with records for crimes like shoplifting or burglary. The few surviving their sentences were listed as ‘Liberes,’ in theory freed inmates. The worst of the worst were ‘Incorrigibles’ or ‘Incos’. ‘Inco’ went straight to the feared jungle work camps where food was short, work hard, danger significant and life expectancy seldom more than a few months. If not the jungle camps, then a permanent posting to Royale was their most likely destination.

Inmates especially hated ‘Doublage’. Any prisoner serving less than eight years had to spend the same amount of time in Guiana as a colonist. Anyone with more than eight years was barred from ever returning to France or leaving Guiana. A two-year sentence effectively became four, assuming the inmate survived.

Conditions were appalling. Food was barely edible and never enough for anybody performing forced labor. Medical care existed, but the prison hospital was poorly equipped and chronically under-staffed. Discipline was brutal, floggings, extended solitary confinement and the guillotine being the order of the day. In the jungle camps inmates worked to stiff daily quotas while underfed, malnourished and brutally disciplined at the slightest infraction. The camps were also breeding grounds for disease. Yellow fever, dysentery, malaria, typhus, cholera and leprosy were commonplace. The jungle was also home for deadly animals like jaguars, snakes, venomous centipedes and flesh-eating ants. The Maroni River was home to piranha and caimans. If these weren’t enough, mosquitoes, leeches and vampire bats were capable of infecting their human hosts with rabies and other blood-borne diseases.

The ‘human factor’

Perhaps the worst aspect was the human factor. The Penal Administration wasn’t concerned about how staff treated inmates provided work quotas were met and the inmates kept in line. Inmates not meeting their daily quota one day would be fed a small amount of bread and water the day after. Every failed day after that meant no food at all until the inmate met a day’s quota and also cleared their backlog of unfinished work. Otherwise, they’d starve, weaken and probably die.

Discipline was harsh, usually brutal. All guards carried pistols, many also carried rifles with orders to kill any inmate attempting escape. They also carried clubs and whips. Inmates could be publicly flogged even for minor infractions. Solitary confinement was a common punishment. Sentences lasting from six months to five years with multiple sentences served consecutively were standard. First escape attempts added two years in solitary to existing sentences. Second attempts added five.

The guillotine at St. Laurent.

For more serious offences, especially attacking or murdering a guard or colonist, the guillotine was freely used. It was operated by convict executioners who were the most hated inmates in the penal system. One executioner, Henri Clasiot, was so hated that other inmates tied him to a tree filled with flesh-eating ants, smeared him with honey and left him to a slow death. At St. Laurent, inmates were paraded before the ‘Merry Widow’ as the guillotine was known and forced to kneel. The execution would take place and the executioner would hold up the severed head while declaiming ‘Justice has been done in the name of the people of France’. It was a nauseatingly brutal spectacle designed to intimidate convicts as much as possible.

The first thought occupying many inmates at Guiana was the same as for inmates everywhere; escape. Naturally, Guiana was chosen to make escape as hard as possible. There were only two realistic ways an escaper could escape the penal colonies; through the jungle and across the sea. The jungle was swarming with hazards; deadly animals, flooded rivers, unfriendly natives, diseases, search parties from the prison and, most hated of all, the ‘Man-hunters.’ Man-hunters were liberes-turned-bounty hunters, tracking escapers through the jungle for a reward, dead or alive. Being paid regardless of their prisoner’s condition, many of them killed recaptured inmates and delivered their bodies rather than endure the extra risk and difficulty of guarding a live prisoner. Other liberes made a lucrative (if loathsome) living by offering to help escapers through the jungle before robbing and killing them. Very, very few escapers were heard from again once they entered the jungle and those who were had either successfully escaped or been recaptured.

The sea was every bit as deadly, but the hazards were different. The border between French Guiana and neighboring Dutch Guiana and British Guiana was the Maroni River, itself infested with piranha and caiman, small crocodiles that took swimmers like any other prey. A boat was the only option. Dutch Guiana also handed back escapers found within its borders, while British Guiana only gave them two weeks before either they left or were returned to St. Laurent under guard. Boats could be stolen, but inmates with money could smuggle a bribe to liberes in return for a boat, compass and provisions to last a few days. Assuming, of course, that the boat wasn’t wrecked in a storm, neighboring countries such as Venezuela and Colombia didn’t decide to hand escapers back at their own discretion and the liberes didn’t take the bribe and still provide nothing useful. The sea wasn’t the most likely option for an escaper; it was simply the least lethal. As a former Warden once put it: “There are two eternal guardians here; the jungle and the sea.”

Failed escapes

Recaptured escapers faced harsh punishments. If a guard or civilian was killed during an escape, the guillotine was a virtual certainly. A first failed escape added two years in the dreaded solitary confinement cells, known as the ‘Man-eater’, the ‘Devourer of men.’ on St. Joseph Island. Second failed attempts added five years more. The solitary block became known for its rule of silence, prisoners being forbidden to speak a single word unless first spoken to by a guard or other staff member. The cells were damp, moldy and disease-ridden. They were also riddled with cockroaches, venomous centipedes and other dangerous animals and the prisoners were deliberately fed poor food only sufficient to keep them alive without keeping them healthy. As a former Warden at St. Joseph described it when Henri Charriere entered for his first two-year sentence: “Here we don’t try to make you mend your ways. We know it’s useless. But we do try to bring you to heel.” A small infraction meant an extra thirty days added to an existing sentence with longer additions for each additional infraction. Other punishments included screening a prisoner’s cell and leaving them for months in total darkness and perhaps cutting their rations by half. This in addition to potentially being guillotined for attacking a guard. Some inmates committed suicide and went unnoticed for weeks due to the rank conditions in the gloomy, disease-ridden cellblock. In short, an inmate didn’t so much live in the ‘Man-eater’ as exist until they died, took their own lives or went insane which, given the conditions, was more than likely.

Royale Island was the home of the ‘Incos’. ‘Incorrgibles’, if not worked to death in jungle camps like Cascade, Charvein and Godebert or along the unfinished roads ‘Route Zero’ and ‘Kilometer 42’ (which were never intended to be finished, existing solely as make-work for slave laborers) would be permanently interned on Royale. Some inmates and officials made a living by taking bribes to have a prisoner’s status changed, making them a regular ‘transported’ instead of an ‘Inco’ and so seeing them shipped back to the mainland where escape was more likely. This was a confidence trick. ‘Inco’s had their status decided back in France. Even the Guiana Penal Administration couldn’t have it altered. The most notorious inmates were quartered in the ‘Crimson Barrack’ where card games ran night and day, staff were too scared to enter unarmed and unescorted and even blatant murders were regularly committed. The threat of violent death firmly discouraged informing on anybody.

Royale had its own hospital, albeit understaffed and under-resourced. It had a chapel, several workshops, was disease-free for most of its existence and was generally the least worst part of the colony except for would-be escapers. The jungle didn’t guard the island’s perimeter and the staff didn’t have to do too much, either. Instead, guard duties were left to the nine miles of open water between Royale and the mainland, the rip tides that could force swimmers and makeshift rafts out past the islands to be lost in the Atlantic and to the man-eating sharks that infested local waters. Even the sharks served the penal system, both as guards and in a deeply macabre form of waste disposal. Convicts on the islands didn’t have their own cemeteries. Deceased inmates were taken out just off the island coastline and tipped overboard at dusk to the sound of a bell tolling. The sharks learned to appear at the sound of the bell when a free meal was guaranteed. To make things even more macabre, the sharks themselves were hunted by local fishermen, sold to the island authorities and fed to the convicts, completing a rather revolting circular food chain. Inmates weren’t deemed worthy of a decent burial, nor did the island have the space to cope with a constant flow of funerals. Burials at sea became the practical, if rather gruesome, solution.

Devil’s Island

The last of the three island prisons was Devil’s Island, also guarded by fierce rip tides and sharks with a few staff on hand too. It’s odd that the smallest and least-used part of the penal system became the totem for the entire network. During the 99 years of the penal colonies only around fifty prisoners were ever kept on Devil’s Island itself. They were all political prisoners and not felons. Devil’s Island owes its fame and symbolic status to having been the unwanted abode of Captain Dreyfus. Falsely accused of espionage, stripped of his rank and sent to Devils Island forever, Dreyfus was eventually pardoned and reinstated after a global campaign to prove both his innocence and the rampant anti-Semitism of his accusers.

Having spent over five years on the island, Dreyfus returned to France for a rehearing, pardon and reinstatement in the French Army, but only after heart-breaking misery at being framed and made a scapegoat by a country he loved and had served honorably throughout. A principal player in the Dreyfus campaign was famed French writer Emile Zola, whose famous essay ‘J’Accuse’ condemned the anti-Semitism in France and the cowardice of the French state in its treatment of Dreyfus while firmly supporting his claims of innocence. As a result of the Dreyfus case at the start of the twentieth century the world finally began to pay attention to Emperor Napoleon’s disastrous and sadistic pet project.

Further unwelcome attention came from Rene Belbenoit and Francis LaGrange, both former inmates of the colonies. Belbenoit, a petty thief given eight years for a small-time burglary, escaped successfully at his fourth attempt and made his way to the United States. His 1938 book ‘Dry Guillotine’, so named because the penal colonies killed as well as a guillotine only more slowly, was reprinted eight times in the first two months since its release and is a collectible to crime buffs and penal historians. LaGrange, a former art forger, also provided unwelcome publicity through sketches and drawings depicting life in the colonies and used in Belbenoit’s book. Increasing international scrutiny forced the French Government to stop sending inmates to the colonies in 1938 and their closure was scheduled until the Second World War intervened. During the war the islands were taken over by the Americans, who feared the Vichy government might try and make them an Axis base of operations. In 1946 the camps and islands began to be gradually phased out. Between 1946 and 1953, when Devil’s Island itself finally closed forever, the camps were shut one after another and the inmates repatriated. Over 300 inmates refused to leave, many staying on in St. Laurent as French Guiana remained a colonial possession. They decided that they had been too changed by their experience to fit back into French society and that Guiana was the only life they could remember. They were probably right. Of those inmates who were repatriated, a substantial number either returned to prison or were declared insane after failing to re-integrate into French society. Some even took their own lives. It was bitterly ironic that many of these men, men who had previously been cast out of French society, found it taking care of them in their last years.

Papillon

It wouldn’t be right not to give a greater mention to Henri ‘Papillon’ Charriere. Papillon’s eponymous book, first published in the 1960s after the colonies had closed, revived unpleasant memories for the French of an episode many would rather have forgotten. Even today the Guiana penal colonies are a taboo subject for many French people. Papillon’s honesty and whether or not he merely appropriated large parts of his book from other inmates’ experiences has been hotly debated, but his storytelling skills are beyond doubt. Although French authorities claim that only around 10% of his claims are true and it’s certainly true that he never served time on Devil’s Island (he was a safecracker convicted of the manslaughter of a pimp, a charge he always denied), the 10% would still be a damning indictment of the Guiana penal system and its purpose of socially cleansing France of its underworld. It even failed to do that, eventually.

There’s another irony in the penal colony story even today, one not recognized by many people. French Guiana is the site of France’s Ariane rocket space program. The rockets are launched from near Kourou, formerly one of the dreaded jungle camps, with control equipment being sited on Devil’s Island. The space project site is constantly under the guard of the French Foreign Legion who also use Guiana for jungle warfare training. Odd really, when you consider that many of those who have joined the Legion at some point might very well have once found themselves headed for Guiana unwillingly, wearing a different type of uniform altogether.

Modern-day France is ashamed of the penal colonies. In the words of writer, ex-convict and former Foreign Legionnaire Erwin James: “France is right to be embarrassed.”

Did you find this article fascinating? If so, tell the world. Tweet about it, like it or share it by clicking on one of the buttons below…

Sources

https://archive.org/details/Dry_Guillotine

http://www.trussel.com/maig/Maigret-in-France/bagn1.htm

http://www.theguardian.com/world/2006/dec/04/france.prisonsandprobation

Papillon, Henri Charriere, Harper Collins, 1999.

Banco, Henri Charriere, Harper Collins, 1994.

Image sources