War broke out between Russia and Japan in 1904. With the war still continuing in 1905, US President Theodore Roosevelt attempted to broker a deal between the two powers to bring about peace. An end result was that Roosevelt controversially became the first American to win the Nobel Peace Prize. Steve Strathmann explains.

You can read an article on Theodore Roosevelt and the American conservation movement here.

Postcard showing locations of Portsmouth Peace Talks (Library of Congress).

In 2009, President Barack Obama was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. He proved to be a controversial choice. The president had been in office for less than a year and the nominations deadline was only eleven days after his inauguration. The prize committee stated that its reason for giving Obama the award was to support the president in his efforts to solve global issues.

Since the first Nobel Peace Prize was awarded in 1901, there have periodically been recipients that have had their qualifications questioned. While President Obama was one of the most recent, an early controversial choice was also an American president: Theodore Roosevelt.

The Russo-Japanese War

Russia and Japan went to war in February of 1904. The two empires had been trying to increase their spheres of influence throughout the Far East and wanted some of the same territory. The Russians occupied Port Arthur (today’s Lüshunkou District, People’s Republic of China), which gave them an ice-free naval base on the Pacific Ocean. The Japanese had once held the port and felt it was unfairly taken from them. Meanwhile, the Japanese were gaining influence in nearby Korea. The Russians looked at this as a threat to Manchuria, which had been under their control since 1900.

The conflict began with a surprise attack on Port Arthur, which eventually settled into a long siege. The war continued to spread into Korea and the Sea of Japan. The Japanese armed forces, whose officers were trained by the British and Germans, were victorious more often than not, but the wins were costly in men and material. The Russians, who believed that the upstart Japanese could not defeat a Western power, continued to throw more of their forces into a losing cause. The most costly decision they made was to send their Baltic Fleet halfway around the world, only to have it destroyed in the Battle of Tsushima on May 27-28, 1905.

At this point in the war, the Japanese secretly approached the United States about helping broker a peace treaty with Russia. They knew that despite having the upper hand, they would soon run out of money if the war continued. Theodore Roosevelt was hoping to maintain a balance of power in the Pacific Ocean, which he felt would favor American trade. Through Secretary of War William Howard Taft, the president said he would assist in the peace process if the Japanese agreed to maintain the Open Door Policy in Manchuria. The Japanese said they would, so Roosevelt approached the Russians.

The Russians proved difficult to bring to the peace table. Tsar Nicholas II still believed that his forces would defeat the Japanese, despite the fact that two of his three fleets had already been destroyed and his army was unable to produce any significant progress. This was par for the course with the tsar, who refused to accept that his empire was teetering on the edge of revolution.

Roosevelt sent George Meyer, the new U.S. ambassador to Russia, to deliver an extremely blunt message to the tsar. Roosevelt told Nicholas II that it was “the judgement of all outsiders, including all of Russia’s most ardent friends, that the present contest is absolutely hopeless and that to continue it would only result in the loss of all of Russia’s possessions in East Asia.” After an hour-long discussion, the Russian leader agreed to send a delegation to peace talks.

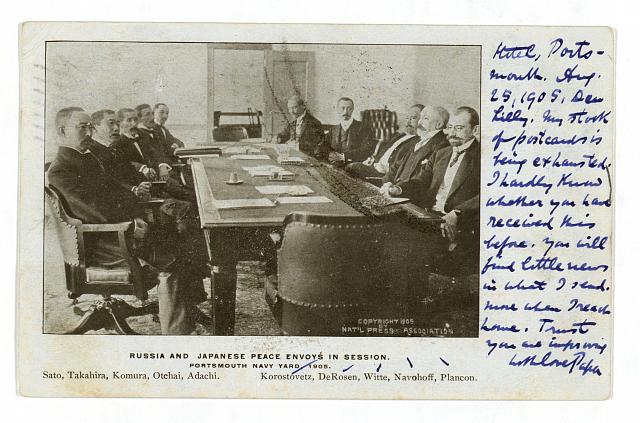

Postcard showing Russian and Japanese peace envoys in session (Library of Congress).

The Portsmouth Peace Talks

The two nations agreed that their negotiations should take place in the United States, but left the final decision up to the Americans. Seeing as the talks would begin in early August, swamp-like Washington, DC, was not an option. Portsmouth, New Hampshire, ended up being Roosevelt’s choice. The small town on the Maine/New Hampshire border was cool during the summer, had ample hotel space, and a naval base with the security and communications facilities needed for such an important event.

Peace envoys from both nations met privately with the president at his summer home in Oyster Bay, New York, before the official start of the talks. The Japanese arrived first with a list of territorial claims that they were going to present to the Russians, along with a demand for an indemnity payment. Roosevelt told them that they should ask for less territory and change their demand for an indemnity payment to a request for reparations. Afterwards, the Russians called on the president at his home. They said that they might negotiate over the territory conquered by the Japanese, but would absolutely refuse to pay any indemnity. The mood was bleak going into the Portsmouth talks.

On August 5, the Russian and Japanese negotiators met with Roosevelt on the USS Mayflower for a welcome luncheon, and were then transported by two American naval vessels to Portsmouth to begin their discussions. Roosevelt remained in Oyster Bay, but was in constant contact with Portsmouth by telegraph.

The negotiations were in a deadlock by August 18. The Tsar’s stance had hardened again and he told his agents not to surrender any territory or agree to any indemnity. Roosevelt chose this moment to step in and called for the Russian ambassador to see him in Oyster Bay. He told him the points on which Russia may find common ground with the Japanese, and suggested that these be discussed in Portsmouth. He also suggested that the Russians offer to pay Japan for the northern half of Sakhalin Island (which Japan had occupied during the war) in place of an indemnity. He also had George Meyer deliver another blunt letter to Nicholas II.

In addition to dealing with the Russians, Roosevelt sent messages around the globe to try and pressure the two sides into a settlement. The German Kaiser, Wilhelm II, was asked to put pressure on his cousin Nicholas II to come to terms with Japan. The British and French also were enlisted to help bring about an agreement. Tokyo received a cable from Roosevelt warning the Japanese that they were looking greedy and needed to settle with Russia to show their ethical leadership to the rest of the world.

At first, these efforts seemed to have little effect and many felt that the Portsmouth talks would end in failure. Then, on August 29, the Russians made their final offer. They would give up the southern half of Sakhalin Island, but make no payments to Japan. The Japanese envoys accepted, stating that Tokyo wanted to end the negotiations and restore peace. The Russo-Japanese War was over, and the treaty was signed on September 5, 1905.

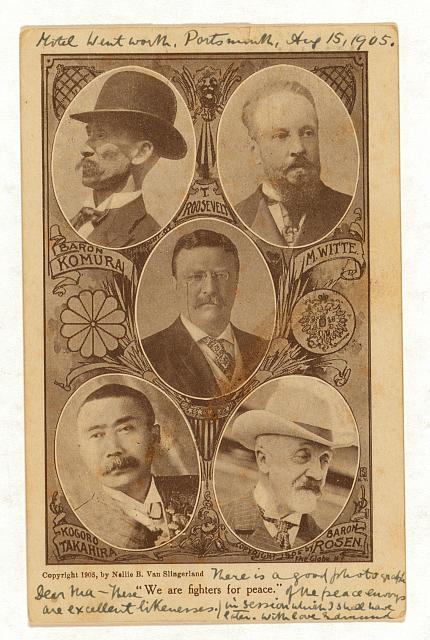

Portraits of Russian peace envoys, Japanese peace envoys and President Theodore Roosevelt (Library of Congress).

The 1906 Nobel Peace Prize

Theodore Roosevelt stated the treaty was “a mighty good thing” for Russia and Japan, as well as for himself. In 1906, he became the first American to win the Nobel Peace Prize. He was awarded the prize for his work on the Treaty of Portsmouth and for his handling of a dispute with Mexico. Several groups came out against his selection. Some felt that his imperialist actions in the Philippines made him a bad choice for the prize. Swedish newspapers also accused the Norwegian selection committee of using the selection to win allies after Norway’s disunion with Sweden in 1905.

Even if his qualifications for the Nobel Peace Prize were questioned, no one could take away Theodore Roosevelt’s accomplishments during the summer of 1905. He brought Russia, a faltering European empire, and Japan, an emerging world power, to the negotiation table and guided them toward a settlement. In addition to this, he helped raise the status of the United States in the world of international diplomacy. Portsmouth would mark the first of many times that the United States made its presence felt in world affairs during the twentieth century.

Did you enjoy the article? If so, tell the world! Share it, like it, or tweet about it by clicking on one of the buttons below!

And remember… You can read an article on Theodore Roosevelt and the American conservation movement here.

Sources

- Morris, Edmund. Theodore Rex. New York: Modern Library, 2001.

- "The Nobel Peace Prize 2009 - Press Release". Nobelprize.org. Nobel Media AB 2014. Web. 2 Dec 2014. <http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/peace/laureates/2009/speedread.html>

- "The Russo-Japanese War Research Society". Russojapanesewar.com. The Russo-Japanese War Research Society 2002. Web. 6 Dec 2014. <http://www.russojapanesewar.com/intro.html>

- "Theodore Roosevelt and the Russo-Japanese War". Russojapanesewar.com. James M. Gallen 2009. Web. 6 Dec 2014. <http://www.russojapanesewar.com/TR.html>

- "Theodore Roosevelt - Facts”. Nobelprize.org. Nobel Media AB 2014. Web. 2 Dec 2014. <http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/peace/laureates/1906/roosevelt-facts.html>

- "The Treaty of Portsmouth and the Russo-Japanese War, 1904-1905 - 1899-1913 - Milestones - Office of the Historian". History.state.gov. Untied States Department of State. Web. 3 Dec 2014. <https://history.state.gov/milestones/1899-1913/portsmouth-treaty>

Images

- Postcard showing locations of Portsmouth Peace Talks (Library of Congress): http://cdn.loc.gov/service/pnp/ppmsca/08100/08184r.jpg. (Picture information at http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2005680006/)

- Postcard showing Russian and Japanese peace envoys in session (Library of Congress): http://cdn.loc.gov/service/pnp/ppmsca/08100/08196r.jpg. (Picture information at http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2005680017/)

- Portraits of Russian peace envoys, Japanese peace envoys and President Theodore Roosevelt (Library of Congress): http://cdn.loc.gov/service/pnp/ppmsca/08100/08185r.jpg. (Picture information at http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2005680007/)