In this article, Matthew Struth tells us the story of the Summit Series, a number of ice hockey games that took place at the height Cold War. These games took place during détente and were anything but friendly…

When the American ping-pong team played in China in 1971, it was seen as a step toward negotiation and cooperation between the USA and China in the Cold War. A year later, Canada made its own attempt to bridge the gap with the USSR, using a game so dear to both nations’ hearts: ice hockey. This was the Summit Series.

The Summit Series, widely considered to be the eight best played and the eight bloodiest and dirtiest ice hockey games of all time, was not called that at the beginning, but it’s a name that has since gained widespread acceptance.

In 1972, Leonid Brezhnev ruled the USSR with an iron but intelligent hand. However, Canada was still dealing with the aftermath of the October Crisis; only the idea of hockey kept even nominal unity in the country. It was in these conditions that Canadian Sports Executive, Joe Kryczka, announced the Canada-USSR Series.

The belief was that the Canadians would easily trounce the Soviets. Even in the Eastern Bloc, the thinking was that Canada would win easily. Orders from Moscow were to play well and win a couple of games. Even the Kremlin didn’t believe the Soviets would win.

The Canadians got one of the greatest wake-ups in their history though: that when it came to hockey, there were others who could match up with the best in the National Hockey League (NHL).

When the first game was done, the Soviets won with a humiliating seven goals to Canada’s three.

A Canadian hockey rink has never been so quiet.

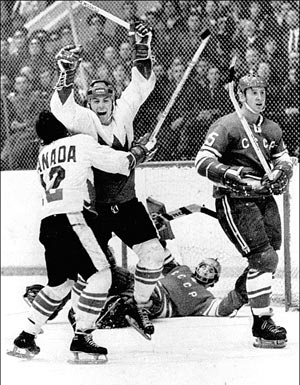

Paul Henderson of Canada celebrating a very important goal in the USSR in September 1972.

On to the USSR

The Canadians were devastated. It showed that just because you could pay a player a lot of money, it did not make him the best in the world. The image that Canadians had always had was that they were the best at hockey, that it was their game, but now... Now Canada struggled with identity, a problem it has always been faced with. Then the game turned to war.

The second game in Toronto saw Canada strike back. Vengeance was on Canada’s mind; the Soviets had humiliated them, and they wanted to return the favor. And they did, with a 4-1 win. The Canadian media soon took to derisively calling the Soviet players “robots” for their lack of emotion while playing the game, an insult that the Soviets took as complimentary for hard-working men. The third game was a tie, but tempers on both sides rose.

The fourth game is the one that Canadians like to forget, if only because of the rude and dishonorable way the Canadian team played. Players held down the Soviet goalie, among other acts that today would have a player expelled from the NHL. The nation was mad at the team and began booing them. This was how Canadians played? But worse, it hurt the team. Some on the team, like Ken Dryden, agreed with the fans, and knew they deserved the boos.

The next four games played in Moscow were not about a shared love of hockey but about the ideological war taking place in the world. The players on the ice mirrored the feelings of the opposing sides as blood was drawn and threats were screamed. To the players, particularly Phil Esposito and Paul Henderson, this was the battle between communism and capitalism.

3,500 Canadians made the trip to the very heart of the Soviet world to cheer on their team. To the Muscovites, the sight was confusing and abnormal. The Russian audience was silent and stoic, while beside them Canadians screamed and cheered.

Blood on the ice

The first game in Russia and fifth in the series saw another Soviet victory. And in the sixth, Canada won; followed by another win in the seventh game.

It was in the seventh game that the unforgivable happened: Soviet player Boris Mikhailov kicked out several times with the blade of his skate, and Canada’s Gary Bergman suffered the worst of it. Bergman’s shin pad was cut through, and his leg was left bleeding. Mikhailov has always regretted the act.

The final game was infamous for the way it played out. Both teams saw winning as crucial to their way of life. The Soviets changed the referees and ordered them to cheat for the USSR. The move infuriated the Canadians, who were more nervous about their position as more militia men were ordered in. Even the Soviet team didn’t like the calls that were handed out, but they could do nothing. An uncounted goal led to unrest as Canadian hockey agent Alan Eagleson tried to have the goal counted, but he was grabbed by militia men. As they were hauling him away, the Canadian players attacked the militia men and freed Eagleson. In the end, Canada scored the three goals needed to first tie, then win, the game.

The NHL adapted and began to use the Soviet methods of training and drilling after the games, methods still in use today. They also brought in rules and regulations that would lessen the physically violent side of hockey, rules that are still contested and disputed. The Series gave Canadians a boost too; hockey was still their game, and they were the best at it. But it was a more respectful Canada that came out of the Series, one that was less arrogant about their game but could still claim to the world that it was the best at it.

The Summit Series healed a nation and gave respect to an enemy. Indeed, after the fall of the Iron Curtain, Russians and other Eastern Europeans were welcomed into the NHL, having more than proven themselves in the Series. A common love for hockey also helped keep the détente period alive, as both sides could now look to a similarity that helped one seem less alien and less of an enemy. But like the détente period, it was not a kind, peaceful event. It was marked by trickery and cheating on both sides, and stood as the example that, though bridges were being built, mistrust and the need to win were a concern on everyone’s minds.

Now, after the hardships of the games have passed, many of the players on both sides look to the others as some of the greatest players ever to hit the ice.

You can find out more about détente by reading our introductory ebook about the middle years of the Cold War here.