In this article, Chris Marsh considers the Scottish aspect of the 17th century civil war, the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. It includes the story of Montrose’s Christmas in Inverary, as well as all manner of other intrigues.

The Marquis of Montrose.

Between the summers of 1644 and 1645 the Marquis of Montrose and Alasdair MacColla led King Charles I’s forces into battle against the armies of the Scottish Covenanting Government on six occasions and won each encounter.

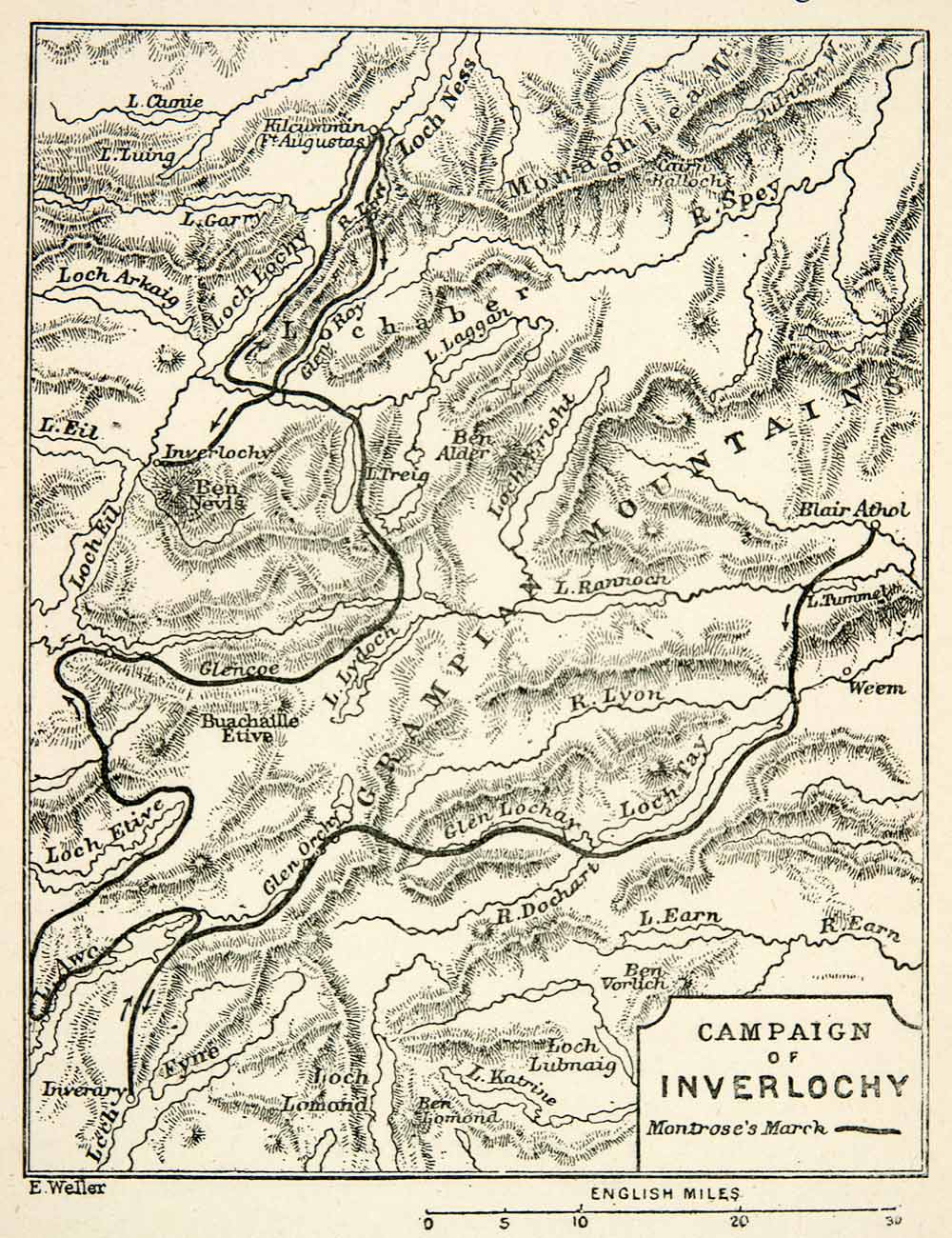

The most celebrated of these victories was at the Battle of Inverlochy, preceded as it was by an epic flank march across snow-covered mountains when the force covered 40 miles in 36 hours before falling on the superior numbers of the Government’s Clan Campbell troops and vanquishing them in the snow, killing some 1,800 in the process. A maneuver described by John Buchan as one of the great exploits in the history of arms in the British Isles.

One of the less celebrated events of this tumultuous year, but which was key to the success that was subsequently achieved, was the decision to maintain the Highland army in the field during the winter, rather than follow the military orthodoxy of the time and seek winter quarters until campaigning could be resumed in the spring.

By mid November they had already won victories against the Government’s armies at Tippermuir and Aberdeen. The Royalist force at this point numbered some 3,000 men. Montrose held the King’s commission as Captain-General although half his army were Irish MacDonalds under the command of Alasdair MacColla. The remainder were Scottish highlanders led by their own respective chieftains with a small leavening of lowland royalists. After the victory at Aberdeen they had split their forces, with Alasdair heading into the west highlands to recruit more men and attack their hereditary Campbell enemies whenever the opportunity arose. While Montrose had remained in the north east maintaining a safe distance between himself and the pursuing Government forces under Archibald Campbell, the Marquis of Argyll and de facto leader of the Covenanting Government. In mid November in Atholl they joined forces once again. But winter was looming and so there was a decision to be made.

Decisions, decisions…

Maintaining an army in the field until the spring presented Montrose with obvious difficulties, particularly with the proximity of most of his men to their homes and the quixotic nature of highlanders which would see them happily head for home with their booty at a moment’s notice.

And so a Council of War was held at Blair Atholl to determine how best to carry the campaign through the winter. This took place in exactly the same location where another such council would be held 45 years later when Bonnie Dundee, James VII’s Lieutenant-General and Montrose’s kinsman, and his Clan Chiefs considered their options before determining to attack General MacKay’s redcoats and defeat them at the Battle of Killiecrankie during the first Jacobite Rising in 1689.

Montrose was not an overly cautious man. He had after all come to Scotland six months earlier with only the King’s commission and two companions and now stood at the head of a substantial force with two victories behind him. However, his underlying military pragmatism persuaded him that at this juncture it would be more prudent to seek food and shelter in the lowlands until the campaign could resume in the spring. That way he could hold his army together and, if necessary, engage in battle with the government’s troops.

This was not, however, the choice of Alasdair or the Chiefs of Clan Donald; the MacDonalds of Sleat, Glengarry, Keppoch and Glencoe. They had a different idea altogether.

Their focus was on their hereditary enemies, Clan Campbell, who had grown prosperous over the previous two centuries largely at the expense of Clan Donald. As the Campbells had acquired their lands by one means or another, Clan Donald had suffered accordingly with many fleeing to Ireland. The Campbells had a ‘knack of winning by bow and sword then holding for all time by seal and parchment.’

The Chief of Clan Campbell, Archibald the Marquis of Argyll, was head of the Covenanting Government and as such held overall command of the armies that Montrose and Alasdair had hitherto met and bested. However, they had still to conclusively defeat these forces before they could join with Prince Rupert and the King’s army in England.

Clan Campbell’s ancestral homeland was the highland fastness of Argyll. Located on the south western fringes of the highlands it was but a short sea journey from the principal trading ports of the more prosperous lowlands while sitting securely behind a mountain shield where only a few narrow passes allowed access. Passes which could easily be held by small numbers of armed men against much greater forces. Here they believed themselves safe.

And this was where Alasdair and the Clan Donald chiefs wanted to attack. A swift and wholly unexpected strike through the mountain passes, he argued, would allow them to eliminate the greater part of the Campbell fighting force whilst delivering a substantial blow to Archibald Campbell’s standing and thus encourage the men of other uncommitted clans to take up arms for the king. And it would solve the problem of supplies. Inverary was a prosperous port and unused to the hardships of winter famine which generally prevailed throughout the rest of the highlands.

The arguments were prolonged. Montrose had eminently sensible concerns about the risks of the proposed venture. And he probably hoped that those of Clan Gordon who were with him, and the other clans from the east would side with him. In the end Alasdair’s view held sway. And so began the invasion of Argyll and the harrying of Clan Campbell.

A map of the Campaign of Inverlochy.

The Harrying of Clan Campbell

The army left Blair Atholl about December 11 on their ambitious march. By the modern tarmacadam road it’s a journey of some 90 miles. In the 17th century, in winter, it was considerably further. They travelled southwest by both shores of Loch Tay, up Glen Dochart past Crianlarich and Tyndrum and into Argyll. With the weather coming from the east there was neither rain nor snow to hinder them and they moved down Loch Awe sweeping all before them. It is apparent that much destruction was wrought by Montrose’s men as they made their way to Inverary. The various sources, as always, are in dispute but clearly death, destruction and plundering on a grand scale characterized their march. It was at this time that Alasdair earned himself the name by which he become known throughout Argyll – fear thollaidh nan tighean, ‘the destroyer of houses.’

Archibald Campbell was well served by his scouts and was alerted to this movement of the Royalist army so he made passage across Scotland to Inverary. Expecting that he would be merely picking off starving stragglers from this bedraggled and windswept force, he began to assemble his fencible clansmen.

Then, suddenly, wild-eyed shepherds rushed through the streets of the town crying that the MacDonalds were at their backs. The bold Archibald boarded the first fishing boat he came to and fled down Loch Fyne to safety leaving his people to the mercy of Montrose and Alasdair. But they would find none. The Royalist army remained in Inverary until the middle of January, satiating their ancient grudges. During this time some 900 Campbell clansmen met their deaths and one thousand head of cattle were appropriated. As observed by Robert Baillie, a prominent Covenanting clergyman of the time: ‘We see there is strength or refuge on earth against the Lord.’

And so in mid January Montrose gave orders for the army to march north. He knew Archibald Campbell would not be slow in preparing his vengeance and there was much winter left to be weathered. The army thus set off on the road that would lead them to the battlefield of Inverlochy in just two short weeks.

This article was written by Chris Marsh who blogs at www.bonniedundee1689.wordpress.com.

Read the next article in this series about Scotland and the Wars of the Three Kingdoms by clicking here.