Nearly exhaustive research has been done on Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s (FDR’s) four national campaigns, his controversial Presidency, and his leadership in WWII. Surprisingly little, however, has focused on his New York State gubernatorial campaign in 1928. This was the campaign and position in which FDR would prove his fitness for the presidency of the Unites States, a position he held from 1933 to 1945.

In part 4, K.R.T. Quirion explains how Roosevelt closed his campaign with a focus on the justice system, the close election results, and the longer-term consequences of Roosevelt’s victory.

You can read part 1 on how Roosevelt overcame a serious illness, polio, to be able to take part in the 1928 campaign here, part 2 on how Roosevelt accepted the nominarion here, and part 3 on Roosevelt’s opponent and how Roosevelt performed on the campaign trail here.

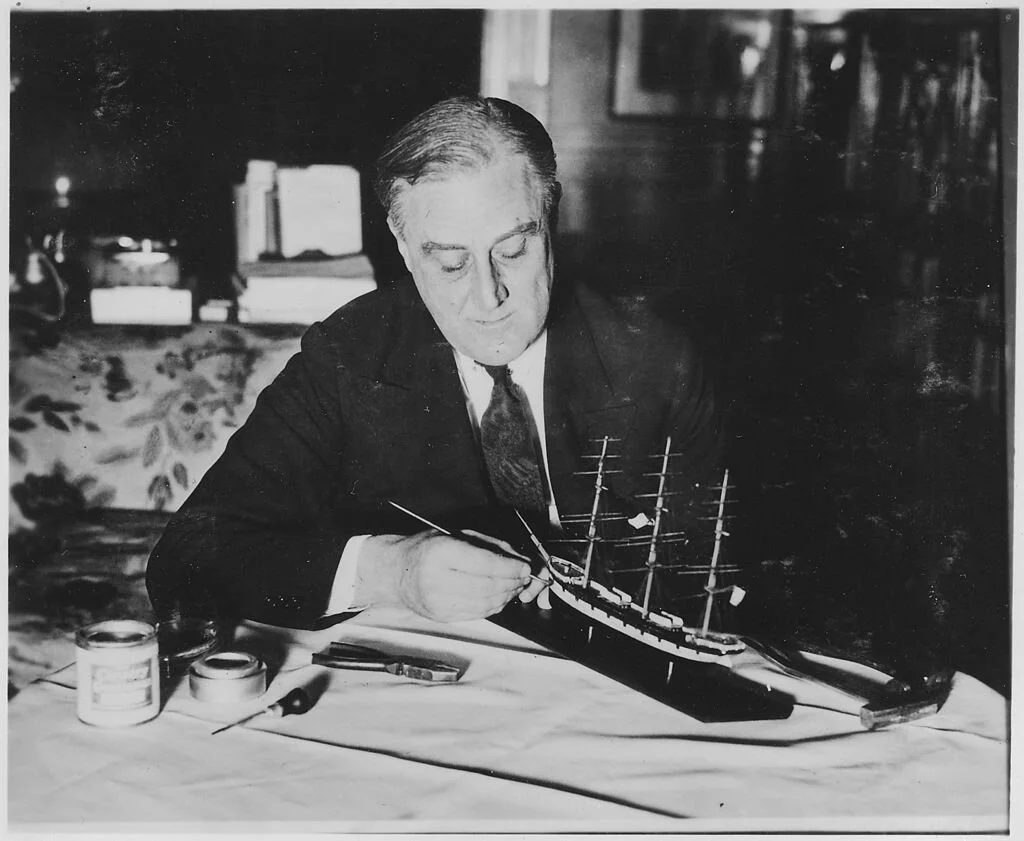

Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1930, while Governor of New York.

Back to New York City

After completing his up-State tour, FDR returned to the Democratic bastion in New York City and its boroughs for the final week of the campaign. There, he continued to develop and expand his platform of populist programs aimed at winning the support of the common man. In Queens, he addressed the problem of urban congestion. According to Roosevelt, a major contributor to overcrowding was the abandonment of farmland by rural populations. To combat this, he promised to actively pursue ways of retaining rural populations.[1] It was in the interest of urban and rural citizens alike that farms be adequately maintained.

However, as rural populations moved to town, city people moved out. Roosevelt believed that two factors were contributing to suburbanization, the growth of popular sports and the democratization of the automobile.[2] New York’s highway program had aided the latter. As to the former, Roosevelt told the audience of Governor Smith’s long legal struggle to acquire for the “great rank file” of New York’s citizenry, adequate parks facilities.[3] He explained how entrenched interests attempted to subject the former Governor to “political embarrassment,” but that Smith fought for what “was approved by the people of the State” and won.[4] In closing, Roosevelt assured the assembled voters that the Democratic Party “will keep on winning as long as it goes ahead with a program of progress.”[5]

The justice system

During the campaign, FDR developed three of the four issues he had outlined in his acceptance speech. On October 30th in the Bronx, he finally addressed the fourth; a Roosevelt administration would be committed to the reforming of New York’s justice system. He considered the administration of justice to be foundational to effective governance.[6] On that account, New Yorkers had much to be proud of in their jurisprudential tradition. However, he believed that reform was necessary to ensure that the State could “keep pace with the fundamental changes in…social conditions.”[7] He warned that a number of factors—such as an increase in population, the growth of cities, and the growth of business—were coalescing resulting in dramatic consequences to the justice system. Specifically, he stated that “these increased complexities of our social relations have added to the difficulties of assuring fundamental justice to the individual man and women.”[8]

First and foremost, Roosevelt advocated for the use of targeted efforts to provide “more modern, more American methods” to address the causes of crime.[9] He hoped to reduce not only the slowness and costliness of litigation but also the volume. Regarding the recent proliferation of civil suits, Roosevelt retorted, “You know, we Americans just love to go to court.”[10]Affirmative steps were needed to reigning in the number of cases being brought to trial. As governor he intended to launch a fact-finding mission to determine “what cases cause the delay and the expense; what kinds of cases take up the time of the courts; what courts are most crowded; and, finally, what cases ought never have come to court at all.”[11]

He discussed other reforms that he would pursue if elected as well. On the civil side, he promised to work for a reduction in the number of jury trials, eliminate perjury, hold members of the bar to a stricter ethical standard, eliminate ambulance chasing and dilatory motions, and finally, to devise new administrative tribunals tasked with freeing the court system of certain kinds of cases.

According to Roosevelt, the criminal justice system needed reform as well. If elected, he proposed twelve steps for study in the coming years. These included a complete overhaul of New York’s prison labor system, the establishment of state detectives to assist District Attorney’s and a revision of the Penal Code.[12] He also suggested the creation of a court system focused on minor crimes. Finally, he declared his intention to revise the firearms law.

Roosevelt lamented that there was often “talk of one law for the rich and another law for the poor.”[13] Looking at the States justice system as a whole, he believed that reform was necessary, and that the people of New York did as well. In closing, he told the voters that “what we need is action, and I propose to do all in my power to see that it is brought about.”[14]

Roosevelt’s whirlwind campaign ended on the 5th of November in Poughkeepsie. There he was greeted by tens of thousands of supporters parading in his honor. Over the course of nineteen days, he had traveled 1,300 miles and had given almost 50 separate speeches. The next morning, he cast his vote at the Hyde Park Town Hall and then retired to his campaign headquarters in the Biltmore Hotel to await the returns.

VICTORY

Up-State Republican leaders had early on declared that they were “nevermore confident in victory” and prophesied a “big increase in the vote” from their districts.[15] At first, the election returns seemed to verify their confidence. Nationally, Hoover had defeated Smith in a landslide that seemed to be taking Roosevelt down with it. By midnight Election Day, votes for Ottinger coming in from up-State had more than offset the Democratic powerhouse of NYC. The papers began calling the race for Ottinger on the morning of the 7th. For Roosevelt, however, it was still too close to concede.

Late night on the 7th, Roosevelt, Flynn, and others in the campaign took notice of the “slowness of the returns from certain upstate counties” where they were confident that Roosevelt had strong support.[16] They suspected that entrenched officials in those districts were up to something. Flynn then issued a statement indicating that key figures of the Democratic State Committee—accompanied by a staff of 100 lawyers—would be heading up-State to investigate suspected voter fraud. Soon thereafter, “many thousands of normally Republican votes” that Roosevelt won began trickling out of the up-State precincts.[17]

As the race began to shift in Roosevelt’s favor, Ottinger released a statement saying that he was ready to “concede nothing.”[18] Republicans were holding out for a few favorable up-State districts as well as about 20,000 absentee ballots. By this time, Roosevelt had returned to his beloved Warm Springs where he was recuperating from the campaign and awaiting its final verdict. On the 18th of November, Ottinger telegrammed Roosevelt his concession stating that “Undoubtedly the final count…will declare your election…You have my heartiest good wishes for a successful administration.”[19]

The election ended with 2,142,975 votes going to Roosevelt and 2,117,411 to Ottinger. Roosevelt was victorious by a razor-thin margin of a mere 25,564 votes. [20] New York State Democrat’s had paid dearly for these votes with campaign funds listed at $5,028,706.02 and expenses of $4,845,774.78. The Republicans, on the other hand, reported astonishingly small receipts of $867,874.25 and expenditures of $832,225.62.[21] Each vote cost the Democratic State Committee $2.26. This was astoundingly expensive when compared to the $0.39 per vote spent by Republicans. [22] In economic terms, the Roosevelt campaign was a disaster. Even in the overall vote, Roosevelt was not very successful, winning only by a plurality of 0.6 percent.[23] Nor had he delivered New York to Smith in the national election as originally hoped. Nonetheless, Roosevelt had fought hard and won.

A personal success

Despite his bitter-sweet victory, the gubernatorial campaign was a fantastic personal success for Roosevelt on several fronts. Given that his previous eight years had been spent living on the periphery of New York politics, his ability to carry the state despite only three weeks of campaigning was a testament to his continued political renown. It was a testament to Howe and Eleanor’s feverish work behind the scenes over those eight years as Roosevelt’s eyes and ears. And, it was a testament to the lasting impact of his “Happy Warrior” speech in 1924.

This combination of factors boosted Roosevelt’s campaign on to an equal footing with Ottinger’s from the start. If he had dropped out of the public eye after contracting polio in 1921, he would have been unlikely to have been considered for the Governorship at all. Assuming he was considered, he would have been at a great disadvantage compared to his highly prominent and active political opponent.

Even though challenges to his health would re-surface, the 1928 gubernatorial race presented Roosevelt with an opportunity to implement strategies to deal with this critical issue. He presented himself as a physically strong candidate that appeared in excellent condition. By appearing indefatigable, despite the breakneck speed of his campaign, voter concerns about his health were assuaged. In face-to-face meetings, New Yorkers were continually surprised “by his vigor.”[24] In the eyes of the electorate, Roosevelt appeared more than capable of handling matters of State despite his physical ailment. In future campaigns, he would repeat these strategies with great success.

The gubernatorial campaign also affirmed Roosevelt’s new Democratic coalition strategy. The pattern of Democratic voter distribution in the 1928 result among cities, towns, and villages as well as between industrial and agricultural areas “indicated a trend” that confirmed the validity of forging a new coalition between labor, agriculture, minority, and urban voters.[25]During the next four years he would cultivate and mold this coalition into the base of the new Democratic Party. He accomplished this in part by working to establish a “permanent national organization, which would ‘extend its…help to…campaigns in between elections and…serve to constantly educate the public.”[26]

Finally, the 1928 campaign elevated Roosevelt as the “heir apparent to the leadership of the Democratic Party.”[27] Following the election, he commissioned a national survey of the Democratic leadership designed to look at several important party matters. Out of the 979 responses from forty-five states “approximately 40% said that they were for Roosevelt or were leaning in his direction…” and “…15 percent specifically declared that he should be the party's next presidential nominee.”[28] From his position as the de facto leader of the Party, Roosevelt was able to further strengthen his new Democratic coalition.

The leadership Roosevelt displayed during the campaign and his first term in office not only secured him a second term as governor but also secured his place at the helm of the Democratic Party. Over the next four years as governor, he developed the policies and strategies that he would later employ as the nation’s chief executive. His response to the stock market crash of 1929 and the following years of economic depression highlighted his ability to cope with a crisis. By 1932, he was once again poised to rendezvous with destiny.

Now, you can read K.R.T Quirion’s recently published series on telegraphy in the US Civil War here, or the secret US Cold War facility in Greenland here.

[1] Roosevelt, “Campaign Address (Excerpts), Queens, N.Y. October 29, 1928,” 55.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid., 56.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid., 59.

[6] Roosevelt, “Campaign Address (Excerpts), Bronx, N.Y. October 30, 1928,” 62

[7] Ibid., 63.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid., 63-4.

[10] Ibid,64.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid., 66.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid.

[15] From a Staff Correspondent of The New York Times, (Oct 18, 1928), “Roosevelt Assails Campaign Bigotry,” New York Times (1923-Current file), 1.

[16] Davis, FDR: The New York Years 1928-1932, 45.

[17] Ibid.

[18] “Ottinger Refuses to Concede Defeat,” (Nov 08, 1928), New York Times (1923-Current File), 1.

[19] “Ottinger Concedes Roosevelt Victory,” 1.

[20] Davis, FDR: The New York Years 1938-1932, 47.

[21] Special to The New York Times, (Nov 27, 1928), “Democrats List Funds at Albany,” New York Times (1923-Current File), 1.

[22] See Table 1.

[23] Davis, FDR: The New York Years 1938-1932, 47.

[24] From a Staff Correspondent of The New York Times, (Oct 22, 1928), “Roosevelt Stands Campaigning Well,” New York Times (1923-Current File), 1.

[25] Davis, FDR: The New York Years 1928-1932, 47.

[26] Earland I. Carlson, “Franklin D. Roosevelt's Post-Mortem of the 1928 Election,” Midwest Journal of Political Science, Vol. 8, No. 3 (Aug., 1964), 300.

[27] From a Staff Correspondent of The New York Times, (Nov 11, 1928), “Roosevelt Hailed by South as Hope of Party in 1932,” New York Times (1923-Current File), 1.

[28] Carlson, “Franklin D. Roosevelt's Post-Mortem of the 1928 Election,” 307.

Bibliography

Primary Sources

“Big Ottinger Vote Predicted Up-State.” (Oct 12, 1928). New York Times (1923-Current File). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/104441542?accountid=12085.

“F.D. Roosevelt Back; Sees Leaders Today.” (Oct 08, 1928). New York Times (1923-Current File). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/104448848?accountid=12085.

F.D. Roosevelt Drive Will Start at Once; To Centre Up-State. (Oct 04, 1928). New York Times (1923-Current File). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/104470038?accountid=12085.

From a Staff Correspondent of The New York Times. (Oct 03, 1928). “Choice of Roosevelt Elates Gov. Smith.” New York Times (1923-Current File). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/104308830?accountid=12085.

From a Staff Correspondent of The New York Times. (Oct 3, 1928). “Ottinger Advances Queens Sewer Issue in Opening Campaign.” New York Times (1923-Current file). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/104425583?accountid=12085

From a Staff Correspondent of The New York Times. (Oct 18, 1928). “Roosevelt Assails Campaign Bigotry.” New York Times (1923-Current file). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/104438214?accountid=12085

From a Staff Correspondent of The New York Times. (Nov 20, 1928). “Roosevelt Begins Work on Message.” New York Times (1923-Current File). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/104443997?accountid=12085.

From a Staff Correspondent of The New York Times. (Nov 24, 1928). “Roosevelt Confers on Labor Program.” New York Times (1923-Current File). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/104398916?accountid=12085.

From a Staff Correspondent of The New York Times. (Nov 11, 1928). “Roosevelt Hailed by South as Hope of Party in 1932.”New York Times (1923-Current File). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/104416279?accountid=12085.

From a Staff Correspondent of The New York Times. (Oct 19, 1928). “Roosevelt Scouts Tariff Prosperity” New York Times (1923-Current File). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/104437219?accountid=12085.

From a Staff Correspondent of The New York Times. (Oct 22, 1928). “Roosevelt Stands Campaigning Well.” New York Times (1923-Current File). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/104310663?accountid=12085.

From a Staff Correspondent of The New York Times, (Oct 3, 1928), “Roosevelt Yields to Smith and Heads State Ticket; Choice Cheers Democrats,” New York Times (1923-Current file). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/104308778?accountid=12085.

“Ottinger Accepts Power as Big Issue.” (Oct 16, 1928). New York Times (1923-Current File). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/104430730?accountid=12085.

“Ottinger Concedes Roosevelt Victory.” (Nov 19, 1928). New York Times (1923-Current File). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/104439338?accountid=12085.

“Ottinger Refuses to Concede Defeat.” (Nov 08, 1928). New York Times (1923-Current File). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/104415539?accountid=12085.

“Ottinger to Visit 14 Up-State Cites.” (Oct 13, 1928). New York Times (1923-Current File). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/104460248?accountid=12085.

Roosevelt, Franklin D. “Acceptance Speech for the Renomination for the Presidency, Philadelphia, Pa.” June 27, 1936. The American Presidency Project. Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley. http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=15314.

“Roosevelt Attacks Theories of Hoover.” (Nov 02, 1928). New York Times (1923-Current File). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/104414619?accountid=12085.

“Roosevelt Confers with Smith to Map Campaign in State.” (Oct 10, 1928). New York Times (1923-Current File). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/104321497?accountid=12085.

“Roosevelt Demands State Keep Power.” (Oct 17, 1928). New York Times (1923-Current File). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/104423627?accountid=12085.

“Roosevelt Opposes Any Move to Revive New York Dry Law.” (Oct 09, 1928). New York Times (1923-Current File). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/104367563?accountid=12085.

Roosevelt, Franklin D. The Public Papers and Addresses of Franklin D. Roosevelt, Vol. 1, The Genesis of the New Deal 1928-1932. New York, NY: Random House. 1938.

“Roosevelt to Make Wide Tour of State.” (Oct 13, 1928). New York Times (1923-Current File). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/104433007?accountid=12085.

Special to The New York Times. (1928, Oct 07). “Bigotry is Receding, Says F.D. Roosevelt.” New York Times (1923-Current File). Retrieved from http://ezproxy.liberty.edu:2048/login?url=http://search.proquest.com/docview/104469322?accountid=12085.

Special to The New York Times. (Nov 27, 1928). “Democrats List Funds at Albany.” New York Times (1923-Current File).Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/104304172?accountid=12085.

Special to The New York Times. (Oct 03, 1928). “Roosevelt Held Out to the Last Minute.” New York Times (1923-Current File). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/104326803?accountid=12085.

Special to The New York Times. (Oct 03, 1928). “Roosevelt Lauded by Mayor Walker.” New York Times (1923-Current File).Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/104326338?accountid=12085.

Woolf., S.J. (1928, Oct 07). “The Two Candidates for the Governorship.” New York Times (1923-Current File). Retrieved from http://ezproxy.liberty.edu:2048/login?url=http://search.proquest.com/docview/104433929?accountid=12085.

Secondary Sources

Davis, Kenneth S. FDR: The Beckoning of Destiny 1882-1928. New York, NY: Random House. 1972.

__________. FDR: The New York Years 1928-1933. New York, NY: Random House. 1985.

Goldberg, Richard Thayer. The Making of Franklin D. Roosevelt: Triumph Over Disability. Cambridge, MA: Abt Books. 1971.

Gunther, John. Roosevelt in Retrospect, A Profile in History. New York, NY: Harper. 1950.

Troy, Gil, Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr., and Fred L. Israel. History of American Presidential Elections: 1789-2008, Vol. II, 1872-1940. New York, NY: Facts on File, 2012.

Journal Articles

Carlson, Earland I. “Franklin D. Roosevelt's Post-Mortem of the 1928 Election.” Midwest Journal of Political Science, Vol. 8, No. 3 (Aug., 1964): pp. 298-308.

Goldman, Armond S., Elisabeth J. Schmalstieg, Daniel H. Freeman, Jr, Daniel A. Goldman and Frank C. Schmalstieg, Jr. “What was the cause of Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s paralytic illness?” Journal of Medical Biography. (11, 2003): pp. 232–240.

Kiewe, Amos. “A Dress Rehearsal for a Presidential Campaign: FDR's Embodied "Run" for the 1928 Governorship.” The Southern Communication Journal. (Winter, 1999): pp. 154-167.