Despite being neighbors and having deep ties with Mexico, most Americans don’t realize that the United States played a key role in sowing the seeds of the Mexican Revolution. In fact, long before the Mexican Revolution even kicked off, three parties emerged, and later their respective interests converged, setting the stage for a violent, bloody uprising. Mexican president Porfirio Diaz, Gilded Age, American industrialists and tycoons, and Mexican revolutionary Ricardo Flores Magón collided, leaving in their wake an indelible influence still felt in both countries today.

Adam Miezio explains.

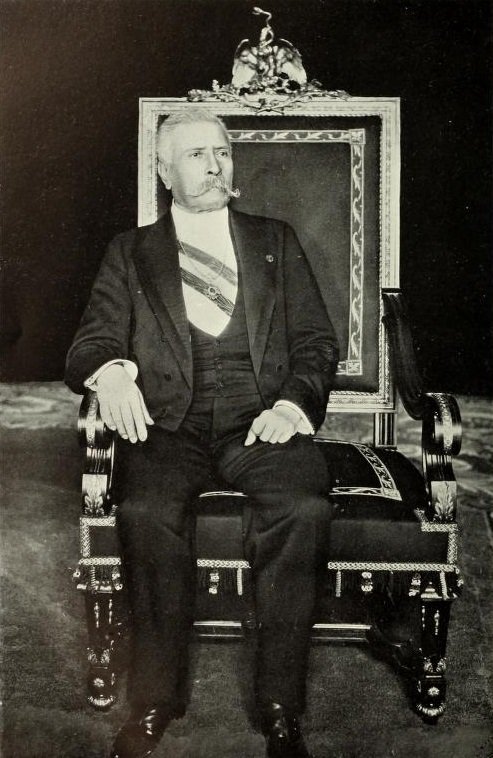

Porfirio Diaz.

The Diaz Master Plan

Mexico had just cast off France’s colonial shackles in 1867. By this time, Mexico had been beaten, bludgeoned and bloodied by centuries worth of European colonial domination. Diaz wanted to pull Mexico up out of its mostly agrarian based economy and turn Mexico into a legitimate, wealthy country on the world stage. Diaz’ plan to modernize Mexico included welcoming foreign investment and production for international markets.

At first, Diaz’ plan paid off. The coups and foreign invasions ended, health and literacy increased and renewed vigor pulsed through Mexico. The progress came at the cost of violent suppression of dissent, imprisoning or executing public challengers, rigging elections and dismissing democratic principles. However, as well-meaning as his intentions may have been, Mexico became a quick and easy target for exploitation from north of the border.

Tired of being the new kid on the block, targeted by bullies, Diaz saw opportunities to open Mexico to capital investment. He was in luck, and all he had to do was look to the U.S for a bit of fresh, oxygen rich, air to breathe new life into Mexico. At the time, the U.S. was experiencing the Gilded Age (1877-1900), an era exemplified by American, economic titans. Although the Spaniards and French took much of the wealth, Mexico was still rich in natural resources: precious metals, oil, and much more. The Gilded Age industrialists saw the vast, untouched wealth Mexico had to offer and couldn’t resist. Diaz welcomed them with open arms to come down to Mexico, do business and plunder the nation’s resources.

Mexico Opens for Business

Diaz opened Mexico for business and:

“…literally sold Mexico to foreign interests. Millions of acres were sold to U.S. agriculture, railroad, and mining companies. Ninety-eight per cent of Mexico’s rural and Indigenous population was left landless, whereas U.S. businessmen and the élite Mexicans who collaborated with them grew rich. The Guggenheim, Rockefeller, and Doheny families in the United States, and the Terrazas and Madero families in Mexico, among many others, reaped the profits of Díaz’s rule. As a result, titans such as Andrew Carnegie claimed that Díaz was “one of the greatest rulers in the world, perhaps the greatest of all, taking into consideration the transformation he has made in Mexico.”

Thus, Mexico and the U.S. consummated a political marriage of financial opportunity and economic convenience. Little did Diaz know that he was helping to start a future, socioeconomic fire. With his coffers filling up, he lost perspective and sight of the ruin that his policies inflicted on Mexico. Nevertheless, Diaz continued the liquidation of Mexico, in turn creating societal fire risk, by selling:

“…land use and mining rights to wealthy landowners and entrepreneurs and to US and European companies. In the process, he confiscated communally held land from peasant communities (ejidos. ) His corruption, favoritism, and dictatorial rule led to resentment by many upper- and middle-class Mexicans. They were educated, white or light-skinned landowners and professionals who resented the lack of democracy and opportunity, but considered themselves superior to the Indian and mestizo masses.”

The collective greed of Diaz and the Gilded Age titans saw no bounds. The 1883 Land Reform Act saw many of Mexico’s natural and material resources sold off to J.P. Morgan, Russell Sage, and the Hearsts. In the late 1890s, sprawling American business investments included sugar, sawmills, cattle ranches and henequen plantations. Oil, copper, lead, zinc, rubber, and agricultural investments swelled American fortunes. Transportation became a double dip. The mined resources were transported by railroad north to the U.S. using the Mexican railway system, which not coincidentally, was also owned by the same Gilded Age tycoons.

In 1911, American investments represented almost 62% of Mexican railroads, 24% of mining, and 1.4% of oil. Foremost among the American industrialists was the oil and railroad magnate and multi-millionaire, Henry Clay Pierce. In 1914, Pierce owned $115,049,000 worth of bonds of the National Railway of Mexico, or about half of its total value. Now the wood and the oxygen for the Mexican Revolution was set in place, with countless Mexican workers and indigenous natives suffering under debt peonage. All that was left, was the match to start the fire.

Portfirio beer. Copyright and re-produced with the permission of Adam Miezio.

The Revolution Finds Its Fire

The decades of the Diaz regime plunged Mexico into a socioeconomic disaster. For the time being, the man who cared least about Mexico’s growing unrest and inequality, was Diaz himself. He was busy lining his pockets and his cronies’, thanks to the American tycoons surging business enterprises in Mexico. This didn’t sit well with Mexico however, and it would be one man’s pen, that would ignite the bonfire of the Mexican Revolution- Ricardo Flores Magón.

In 1901, in San Luis Potosi, Magón began sparking the match by decrying the Diaz regime as a “den of thieves.” Many Mexicans agreed with the sentiment of the already two decade old regime stealing their lands, rights and wages, but it was never heard or discussed publicly. Ricardo Flores Magón and his brothers became radical dissidents. Along with radical and liberal intellectuals, Magón gained political influence. He was backed by journalists, American dissidents, and thousands of poor workers, farmers, miners, and cotton pickers called magonistas. Magón never strayed far from their side, as the magonistas could always have their leader’s writings in hand.

A year prior, Magón founded the newspaper Regeneración, the leading, revolutionary voice of Mexico. The newspaper circulated far and wide across Mexico, and soon landed Magón in jail. Afterwards, he fled in exile to Canada and the U.S. While in the U.S., he lived in various cities (El Paso, St. Louis, San Antonio and Los Angeles), where he hid, organized, wrote and published Regeneración. By 1905, the newspaper enjoyed a circulation of 20,000 and had gained one quite notable reader- Emiliano Zapata.

While the socialist Regeneración was published from the U.S., Magón gained notable support and help from American socialists and anarchists like Mother Jones and Emma Goldman. Foreign countries weren’t enough to protect and hide Magón. Although he never gained the high profile status of revolutionaries Emiliano Zapata and Pancho Villa, Magón had achieved most wanted status.

Inevitable American Pressure

The percolating unrest south of the border drew the attention of the White House. At a time when it wasn’t common practice for U.S. presidents to meet respective heads of state on their own territory, President William Howard Taft and Mexican President Porfirio Díaz met in El Paso and Ciudad Juárez. Up until that point, it was the first meeting between American and Mexican heads-of-state. Around that time, Taft wrote a letter, saying “there would be a revolution growing out of the selection of his successor. As Americans have about $2,000,000 of capital invested in the country, it is inevitable that in case of a revolution or internecine strife we should interfere, and I sincerely hope that the old man’s official life will extend beyond mine, for that trouble would present a problem of the utmost difficulty.”

Magón and his masses of magonistas were still determined to oust Diaz. They had endured more than enough plunder of their beloved country by American imperialists like Guggenheim and Rockefeller to fail. Unfortunately for Magón, the Diaz regime was now collaborating with American officials to hunt him down. U.S. agents of the Bureau of Investigation (precursor to the F.B.I.) were tracking Magón and his whereabouts. Magón also had feds from the U.S. Departments of War, Treasury, Justice and State on his tail, not to mention hordes of police, sheriffs and spies. Magón lays claim to being one of the F.B.I.’s first cases and most wanted men.

Eventually, Magón was apprehended in Los Angeles, on August 23, 1907.

Magón was released from prison in 1910, the same year that the Mexican Revolution began. Magón continued publishing Regeneración in Los Angeles, as the magonistas, led by Zapata and Villa, waged war south of the border. Besides inadvertently helping to launch the F.B.I., Magón left another influential legacy behind - Mexican immigration.

The Mexican Revolution Jump Starts Immigration

As the Mexican Revolution kicked off, Mexicans fleeing the violence, poured into the U.S. Insurgents, refugees and campesinos alike came by boat or by foot. Those who came by boat, disembarked in San Francisco, and took trains to Los Angeles and Chicago. Those who came by foot, flooded into the southwest, especially Texas. Laredo and El Paso became two of the most popular destinations.

The Mexican population in El Paso grew exponentially between 1910 and 1916, from approximately 9,000 to nearly 33,000, as Mexican refugees, impacted by the Revolution, fled north. The refugees included not only the poor but also, by one city newspaper’s estimation, “tens of thousands of Mexicans of the best classes,” leading El Paso to displace “San Antonio, New Orleans, St. Louis, New York, and Los Angeles [as the] formerly dominant capitals in the mind of the average welltodo [sic] Mexican.”

The revolution blazed across Mexico. Peasants, workers, mestizos, intellectuals, business owners and white-skinned Mexicans were forced into competing groups. The undemocratic institutions, unequal land distribution and deep rooted inequality sown by Diaz’ economic policies affected each socioeconomic class in a unique way. The unfortunate reality didn’t help to create solidarity during the revolution. Some success did come fast though.

Diaz Out, and Magón Dead along with his Legacy

By May 1911, Diaz was defeated and on his way to exile in France. Even with the 30-year dictatorship vanquished, the Mexican Revolution still raged on for 6 more years. At the time, Magón lived in El Monte, part of the San Gabriel Valley in Los Angeles County. By this time, he had become fully radicalized and made no effort to hide his anarchist politics. His radical anarchism didn’t sit well among some magonistas, who were more moderate and socialist. Magon began losing support and notoriety, but he had one last gasp in the annals of history.

While WWI broke out, coinciding with the Mexican Revolution, Magon published an anti-war manifesto in 1918. The last stroke of his pen sealed his fate. In 1919, U.S. president Woodrow Wilson launched the Palmer raids. The raids unleashed a wholesale crackdown on dissidents and leftists, foremost among them socialists, communists and anarchists. Magón got swept up along with notable contemporary Eugene V. Debs. Magón was charged with sedition under the Espionage Act of 1917. He was convicted and sentenced to 20 years in prison, and died at age 48 in Fort Leavenworth penitentiary in Kansas.

Sadly, Magon spent most of the Mexican Revolution in prison, cut off from the movement he started. His increasing militancy and anarchism didn’t provide the cohesion and solidarity that Mexicans sought. Although he earned the credit of the Mexican Revolution’s “intellectual author,” his legacy now lies in the shadows of timeless legends Emiliano Zapata and Pancho Villa.

If you found that piece of interest, join us for free by clicking here.