As Gandalf tells us in The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers, "Perilous to us all are the devices of an art which we do not possess ourselves." Of course, Gandalf is talking about a dangerous, magical object that can communicate across space and time: a palantír stone. But the message rings true, too, about the powers of language and writing, which--like a palantír stone--can also traverse boundaries of space and time. Step into a library and you might have dialogues with thousands of the dead.

Some of history's most dangerous and destabilizing figures were masters of the art of speech. They possessed great oratorical skills, but were devoid of a greater sense of ethics. In Plato's reckoning, a true rhetorician must unite their art of speech with philosophy. After all, if we do not possess ourselves a sense of how language can persuade us and work us over, then we will be all the more susceptible to those who might wield rhetoric against us.

In the following excerpt, Dr. Daniel Lawrence (author of a recent book here: Amazon US | Amazon UK) goes back to the world of the ancient Greeks, where one's ability to speak well could literally be a matter of life and death. It's no wonder, given these circumstances, that an art of persuasion and various theories of language and perception emerged. Yet, as many rhetorical scholars have now documented, many different people at many different times and places developed arts and theories of writing and speech: the ancient Egyptians, the ancient Chinese, and various Indigenous peoples across the world. Wherever there is writing, language, and technology, there seems to emerge a human critique of its power. The author believes this rich tradition of critique--this art of rhetoric--is precisely what we need more of in our world today to help combat the growing dangers of digital disinformation and the unsettling, persuasive abilities of artificial intelligence.

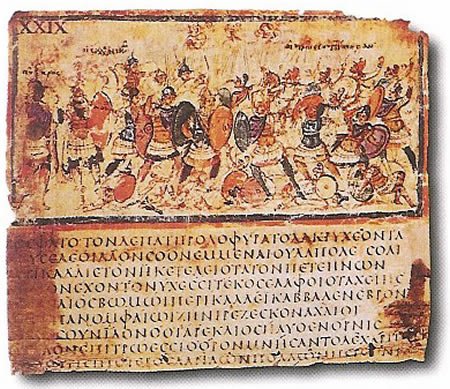

Oratorical skills are referenced in Homer’s Iliad. Above picture: Iliad, Book VIII, lines 245–253.

The ancient Greeks loved speeches. In the beginning of Phaedrus, one of my favorite dialogues by Plato, the titular character Phaedrus tells Socrates that he has just returned from a morning of making speeches with his friend Lysias. This would seem to be a rather funny thing in today’s world: to meet a friend for lunch, ask them how they spent their morning, and be told, “Oh, I was just over at Jane’s apartment. We were making speeches all morning.” Though this would not be a common occurrence today, the art of making speeches was close to the heart of ancient Greek culture. In a world where writing was a relatively new technology, writing tools and materials were expensive, and there was a reliance on oral tradition. Thus, speechmaking was a valued pastime. In many ways, this same desire for communication and storytelling is now fed by our media addictions: television, YouTube, film, podcasts, or binging a Netflix series. We don’t want to dismiss the important differences in our cultures, but we also shouldn’t forget just how similar humans can be across time and space.

Not all fun

But rhetoric wasn’t all fun, games, and entertainment for the ancient Greeks. The renowned classicist and scholar of rhetoric, George Kennedy, explains in his seminal A New History of Classical Rhetoric that this fascination with speeches was at least partially due to the vital, life-saving necessity of wielding language persuasively. Because there was no regular system of legal representation in ancient Greece, citizens would often be required to defend themselves in a court of law or to lay out their case against an opponent. In these early days of democratic society, your ability to speak could literally be a matter of life or death. If your neighbor accused you of stealing their goat—or worse, their horse—then you better have been able to make a compelling argument about why it wasn’t possible that you stole it as you proved your innocence. Perhaps you would make an appeal to ethos—that is, your character and credibility—and say, “I am an honest and law-abiding citizen of Athens. How could a person like me commit such a crime?” Perhaps you would make an appeal to pathos—that is, the emotions of your listeners—by pleading, “I am a father of five children and must work hard to provide for them. Would you rob these children of their father by imprisoning me based on the false claims of this greedy accuser?” Or perhaps you would appeal to the logos (or logic) of the audience and claim, “I was all day yesterday at the Theatre of Dionysus, a fact to which many of my fellow citizens can attest. How could I have been in two places at once?”

Today, we don’t take language seriously enough. The rhetorician Lloyd Bitzer wrote in his oft-cited essay (and bane of disinterested undergraduate students everywhere) “The Rhetorical Situation” that “rhetoric is a mode of altering reality,” not by physically moving material objects around, but by “the creation of discourse which changes reality through the mediation of thought and action.” This is just an academic way of saying that speech and language can literally change the way we perceive the world, the way we think, and the way we act. And certainly, we know this to be the case. We might hear a powerful sermon and be swayed into a life of service to a god, or we might see a compelling video advertisement which, even imperceptibly or insensibly, cements an idea in our mind of which make and model of automobile we want to purchase. Language can have life-altering effects on us. We may be convinced to take a job in a new city or to vote for a particular political candidate. Gorgias, the rockstar rhetorician of ancient Greece, likened language to a kind of drug, or pharmakon. To me, that appears to be a reasonable explanation for the brainwashing and spellbinding experienced by the German population under Hitler in the early-to-mid twentieth century. But then, it’s easy to see when it’s happening to other people: “How could all those Germans have just fallen right in line with that evil man? Couldn’t they see through his lies?” No, most could not. It’s easy to see when others are being persuaded. It’s painful and difficult to observe it in ourselves. We like to believe we are immune to persuasion, but we are all persuadable.

Persuasion

It’s not just language that is persuasive, though. It is the combined effects of rhetoric that persuade us. Hitler’s powers of persuasion included his mannerisms, gesticulations, the timbre and inflection of his voice, his word choice (diction), the way he constructed sentences (syntax), and his use of rhetorical techniques like allusion or antithesis. It was his use of symbolism and architecture (such as the golden eagle, standard in the grand Nazi-party rallies and the ubiquitous swastika) as well as his deft wielding of then-new technologies such as radio, film, and fast travel by airplane. As Quintilian told us, even “the mere look of a man can be persuasive.” Contemporary psychology tells us just as much. Tall people make more money over their lifetime, according to findings on a “height-salary link” that was documented in one study by Timothy A. Judge, PhD and Daniel M. Cable, PhD. In another uncomfortable set of studies, researchers found that attractive women received higher grades in college courses—an effect that diminishes when teaching is conducted remotely and online. We like to think that we’re objective, rational, and fair, but there’s a broad expanse of research that shows the opposite to be true; we’re easily persuaded and carry many deeply held biases and values within us, and these affect the way we perceive and interact with others and the world around us.

We don’t understand, fully, comprehensively, scientifically, how persuasion works. There is, at present, no satisfactory or complete picture of persuasion in the neurological, psychological, rhetorical, or sociological literature. It’s a tricky beast to pin down precisely. Persuasion is complicated. We are practically left with the same conundrum today as our ancestors faced thousands of years ago. In some sense, I am grateful for this. I have no doubt that if a universal theory of persuasion were discovered, corporations, political parties, and governments would take full advantage of the knowledge, and democracy would be in further jeopardy. Yet, even without a universal theory of persuasion, this is essentially the place we find ourselves in. Using imagery, video, hyper-targeted social media advertisements, psychographic profiling techniques, big data, modern computing power, and complex technological distribution mechanisms, persuasion and propaganda have become more powerful and more dangerous today than ever before. As I will write about later in this book, the UK firm Cambridge Analytica used weaponized social media advertising strategies to influence elections all over the world, while companies at present are spending more money on digital advertising than print, billboards, mailers, leaflets, radio, television, magazine, newspaper, and all other forms of traditional advertising combined. And they called those they targeted with the bulk of their budget “The Persuadables.” The Persuadables were a demographic of centrists Cambridge Analytica profiled as being on-the-fence and able to be pushed to vote for one candidate over another. While we don’t know the extent to which Cambridge Analytica influenced presidential results in the U.S. in 2016, we can rightly assume that companies wouldn’t be paying for such services if they didn’t yield results. Digital disinformation is a massive global undertaking, and we are the targets.

Conclusion

Now, I’m not suggesting that we return to the oral culture of the ancient Greeks and all start making speeches as a form of entertainment. (It might be fun, though.) We can’t force a cultural change like that. But what should be most shocking to us is that we have completely abandoned the one field of study that deals directly with disinformation, propaganda, and information literacy in this time of crisis, when there is more technologically advanced disinformation threatening democracy than ever be- fore in the history of humanity. The field of study that deals with these extraordinary questions of truth, credibility, disinformation, propaganda, and information literacy is the study of rhetoric. I know that teaching and learning about rhetoric can be interesting (and even fun) when done right. Furthermore, there may not be anything more powerful for a person to learn than how to speak and write effectively and persuasively. How can we live in a time like this and not teach our children about rhetoric, the field of study that could empower them to disarm disinformation, advocate for their rights and values in an increasingly polarized realm of political discourse, and be resilient to the thousands of advertisements and propagandic messages that are launched at them daily from smart phones, computer screens, and the increasing number of screens in our homes, schools, and places of work? How else to protect them from the idealogues that fill our schools, companies, and communities? Rhetoric is that secret, ancient discipline that can help us in our great time of need. We are all persuadables, and we need help.

Dr. Daniel Lawrence has a recently published book: Disinformed: A History of Humanity's Search for the Truth. It is available here: Amazon US | Amazon UK