In their novel, The Gilded Age, Mark Twain and Charles Dudley Warner noted that the Civil War and its immediate aftermath, ‘uprooted institutions that were centuries old, changed the politics of a people, and wrought so profoundly upon the entire national character that the influence cannot be measured short of two or three generations.’ In the hope of rebuilding the broken pieces together, every aspect of society, from urban life to class system to agriculture and industry had to be touched upon. The process of institutional transformation came to be known as the Reconstruction (1865-1877).

Aarushi Anand gives her take on the Reconstruction era.

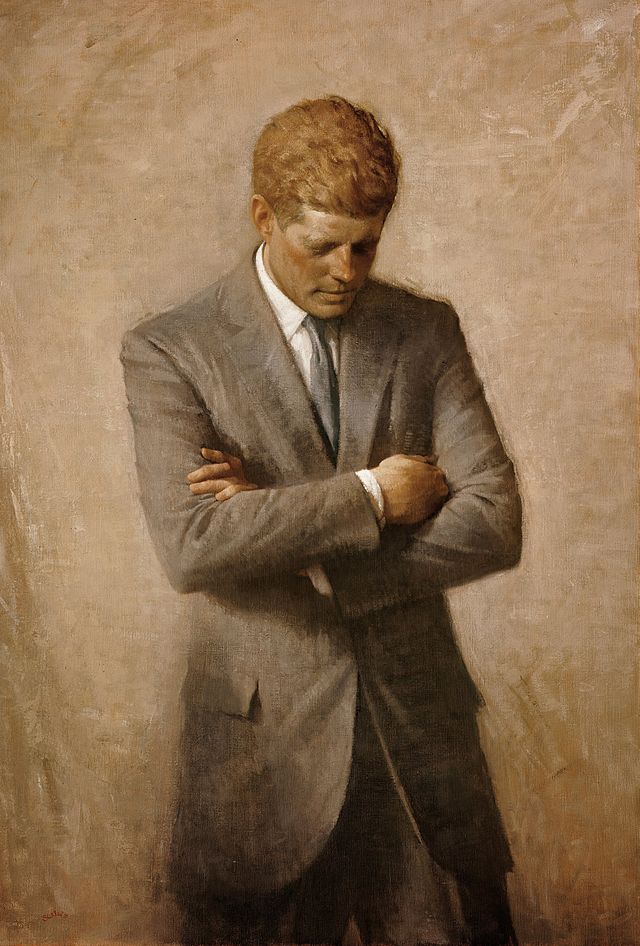

A Visit from the Old Mistress. Winslow Homer, 1876.

The task of reconstructing the union initiated the transition from conflict to peace by targeting fundamental components of the rebuilding framework. Restoration of "physical infrastructure," a traditional area of strength, involved expensive maintenance services like rebuilding rail and road networks, reconnection of interrupted water supply and racial desegregation of schools and hospitals. The process of social and emotional reintegration becomes more difficult when conflicts, especially those that last for a long period, damage the fabric of society and render a return to the past impossible or undesirable. Slavery was formally outlawed in the entire United States through the 13th amendment (1865). In order to determine what kind of reconstruction policies to implement, the nation had to first decide whether the Confederacy be treated with leniency or as a conquered foe?

President Abraham Lincoln was of the lenient persuasion as is evident from his second inaugural address “with malice toward none; with charity for all...let us strive on to finish the work we are in, to bind up the nation's wounds.” He started off the Ten-Percent Plan (1865–87) which imposed a minimum requirement of political loyalty for southern states to rejoin the Union. Following President Lincoln's assassination, his successor Andrew Johnson and his administration drafted what is now known as Presidential Reconstruction. Johnson, a former enslaver, was deeply racist and recreated conditions in the South which were largely the same as they were before the war. Case in point, he set up all-white government and appointed a trust-worthy provisional governor in the South. During his administration, a number of draconian laws known as the Black Codes (1865–1866) were passed, limiting the civil and political rights of blacks in the South. Since most freed blacks had only the skills to work on plantations the black code stipulated that black workers would be legally bound to the plantation owner. Each year blacks were required to sign a labor contract to work for a white employer and if they did not do so they'd be arrested for vagrancy and then sold off. According to several historians’ Black codes marked the continuation of ‘slavery in all but name.’

The Radical Republicans, who at the time-controlled Congress, were opposed to Johnson's clemency or his role in the South's resegregation. To this end, they passed 2 pieces of law that granted black citizenship rights while also calling for the racial integration of workplaces, neighborhoods, schools, and universities. First, the Freedmen's Bureau, a coalition of Northern officials and Union Soldiers, was set up all over the South. Its goal was to help reunite families separated by slavery which over the course of 250 years had split apart millions of people. In one of its main roles, securing fair labor contracts, the Bureau proved to be redundant. The Bureau was crucial in helping Black Americans pursue formal education. According to historian James McPherson, there were over 1,000 schools in existence by 1870. Second, the Civil Rights Act of 1866 granted Black Americans citizenship and guaranteed their equal civil rights, including the ability to enter into agreements, acquire property, and give testimony in court. Republicans sought the 14th constitutional amendment (1868) to bolster these rights and prevent overturning of the central government's directions out of a fear that the Civil Rights Act would be struck down. For nearly a century, the promise of the 15th Amendment would not be fully realized. African Americans in Southern states were successfully denied the right to vote through the imposition of poll taxes, literacy tests, and other techniques (e.g. permitting only registered voters since the 1860s to vote).

CARPETBAGGERS

Despite being eligible to run in elections, it was a harsh reality that an all-black government would not succeed and would require white allies to form an inter-racial coalition. This raises the issue of whether white people are willing to participate in the reconstruction of government in conjunction with African-American voters. The carpetbaggers come first for the purpose. Carpetbagger is a political term used to describe a northerner who united with blacks and the Republican Party and advocated the new constitutional rights of African-Americans. During the Civil War, Union soldiers and commanders who chose to remain in the South after the army were demobilized made up the majority of the northerners who traveled there. In office, the performance of the carpetbaggers was mixed. While some were dishonest, others, “were economy-minded and strictly honest.” For instance, carpetbag lawyer Albion W. Tourgee contributed to the drafting of the North Carolina Constitution (1868), opposed the Ku Klux Klan (1869–1870) and fought for blacks in Louisiana against a law requiring segregation in railroad cars (Plessy v. Ferguson, 1896).

SCALAWAGS

Although the carpetbaggers managed to occupy positions of authority, they were insufficient to form a voting bloc. So, in terms of voting power, the other real group is the so-called scalawags. The majority of them were Whigs, lower-class whites, and Southern unionists who opposed secession. James Lusk Alcorn, one of Mississippi's wealthiest planters, a large slaveholder, and a Whig opposed to secession, popularized the term "harnessed revolution," which refers to the period of time when White people like himself would lead the Reconstruction process. By far less affluent white people in the upcountry made up the greatest number of scalawags. The number of white Republicans in states like Tennessee, North Carolina, Arkansas, Alabama, and Georgia was sizable. These Republicans did not want the planters to regain power and felt that the only option is black suffrage. Internal conflict also plagued these regions

KU KLUX KLAN

It is crucial to remember that white supremacist opposition to the Radical Republicans' agenda manifested itself as covert organizations. The Ku Klux Klan was one such group that fostered homegrown terrorism in the United States. Members of the Klan rode across the nation in white sheets throughout the night to conceal themselves and use violence for political purposes. Violence was used to frighten black and white Republicans to keep them from casting ballots. Additionally, it was done to unite white people under the idea that race was the main concern. The glorification of the Ku Klux Klan in the movie "Birth of a Nation" is based in part on the notion that the group was merely exploiting people's superstitions.

The ferociousness of Ku Klux Klan attacks in 1870 and 1871 convinced many that additional laws, either state or federal, along with a vigorous enforcement, were essential to the security of the new order. Carpetbagger Amos Lovering, a former Indiana judge, contends that "universal education in morals and mind" is the only effective way to permanently quell the Klan's brutality. Many of these measures failed. In the South, most white people continued to own weapons. The government was unwilling to deploy armed blacks after the white knight riders since such a move would only intensify racial tensions.

W.E.B Du Bois, described the Reconstruction period as a moment where "...the slave went free; stood a brief moment in the sun; then moved back again toward slavery." By the end of the 19th century, 2,500 Black people would be lynched across the South. Occasionally people say that Reconstruction failed, but it would be more accurate to say that it was violently overthrown. It did not fail to succeed because Black people were incapable of governance but because white Southerners did everything in their power to obstruct Black mobility and opportunity.

CIVIL RIGHTS

In a variety of ways, reconstruction prepared the way for future struggle. The 1960s Civil Rights Movement was frequently referred to as the second reconstruction, the country's second attempt to face the issue of racial equality in the law, politics, and society. The movement was a nonviolent social movement and campaign to abolish legalized racial segregation, discrimination, and disenfranchisement throughout the United States. Reconstruction also opened discussion on how to deal with domestic terrorism. Racist organizations such as the Ku Klux Klan thrived throughout reconstruction and made its imprint on American society via racial bloodshed. The Black Power movement emphasized how little tangible progress had been made since the 1960s Civil Rights Movement and how African-Americans continued to experience discrimination in jobs, housing, education, and politics. Reconstruction is still relevant today because it raises fundamental questions about American society that are still being debated, such as who is eligible to become a citizen, how the federal government interacts with the states, who is in charge of defending citizens' fundamental rights, and how one deals with homegrown terrorism.

What do you think of the article? Let us know below.

References

1. Foner, Eric. Give Me Liberty! An American History: Seagull Fourth Edition. Vol. WW Norton & Company, 2013.

2. Foner, Eric. "The new view of reconstruction." American Heritage 34, no. 6 (1983).

3. Grob, Gerald N., and George Athan Billias. "Interpretations of American History Patterns and Perspectives." (1972).

4. Harris, William C. "The Creed of the Carpetbaggers: The Case of Mississippi." The Journal of Southern History 40, no. 2 (1974): 199-224.

5. Trelease, Allen W. "Who were the Scalawags?" The Journal of Southern History 29, no. 4 (1963): 445-468.