How did Europe grow quickly and become a hub of innovation, making it a global leader in trade and military strength? Here, Ilyas Ali gives us his take.

The 1836 Siege of Constantine during the French conquest of Algeria.

Historians disagree on how Europe came to be so powerful - to say the least.

But one thing is for certain and which all agree on. And that is that to find the answer, we must not look at what happened or who did during an isolated point in time.

Rather, we must grasp the long-term changes that brought Europe to its current position.

Troublesome Geography

One thing that is striking about Europe in 1500 was its political fragmentation. And unlike in places such as China, Europe’s political disunity was not a temporary affair.

In fact, this is as it had always been. Even the mighty Roman Empire had difficulty conquering areas north of the Rhine and Danube rivers.

In comparison to the Ottomans and Chinese, the Europeans were divided into smaller kingdoms, lordships, clans, and confederations in the East.

And the cause that prevented anyone from conquering Europe was geography.

Europe lacked the vast open plains that enabled the Mongols to conquer on horseback in Asia.

Nor were there large rivers like the Nile, Euphrates, or the Yangtze which provided nourishment to easily conquerable peasant populations living along its banks.

Europe was divided by mountains and forests, making it inaccessible for conquerors wishing to dominate the continent. Also, the climate varied considerably across the continent, which made that goal harder still.

But whilst it denied the unification of the continent, it also acted as a barrier to invasion from elsewhere.

Indeed, despite the Mongol horde swiftly conquering much of Asia, it was these same mountains and forests which saved Europe.

Free Economy

Because its geography supported dispersed power, this greatly aided the growth of a free European economy.

Do you remember how Europe had different climates across the continent?

This same variable climate allowed for different products to be made and traded.

For example, due to their different climates, an Italian city-state would sell grapes the English couldn't grow. And in return, the English sent fish from the Atlantic.

And another advantage Europe possessed was its many navigable rivers which allowed the easy transport of goods. And to make transporting goods even easier, many pathways were made through forests and mountains.

And dispersed political power also meant that commerce could never be fully suppressed in Europe. This was a recurring problem that Eastern empires had, but not so much in Europe.

If a king taxed his merchants too much or stopped trade completely, they would move to a more business-friendly part of Europe. And they would take his tax money with them.

Because of this, over time European statesmen learnt that it was in their best interests to strike a deal with these merchants and tradesmen. They would give them a law and order, and a decent judicial system. In return, those merchants would give them tax money to spend on their state and military ambitions.

Military Superiority

Despite its geographic situation, there was still one way to unify Europe: to have superior military technology.

This is what happened with the ‘gunpowder empires’ of the East. For instance, in Japan, the feudal warlord Hideyoshi brought together the country by obtaining cannons and guns that his rivals lacked. This technological superiority allowed him to unify Japan.

And it wasn’t at all impossible for a ‘gunpowder empire’ to arise in Europe. By 1500 C.E., already the French and English had amassed enough artillery at home to crush any internal enemy who rebelled against the state.

Despite Europe having powerful military forces, no one was able to conquer the entire continent -although the Habsburgs would come close though.

So why did this not happen?

The reason this didn’t happen was because of that same decentralization spoken of before. Due to political decentralization, an arms race occurred among all European states.

Europe, you see, had a habit of constantly going to war. To survive, every European polity aimed to be militarily stronger than its neighbors.

This created a competitive economic climate to create superior military technology.

But this also meant that no single power had complete access to the best military technology. The cannon, for example, was being built in central Europe, Milan, Malaga, Sweden, etc.

Nor could one power easily proliferate the most superior ships. There were shipbuilding ports all across the Baltic to the Black Sea, all locked in fierce competition.

One might ask at this point; wouldn’t the disunited European armies easily be crushed by the mighty Ottoman and Chinese armies of the East?

And the answer would probably be yes.

Europe was definitely lagging behind the Eastern empires in the 16th century. However, by the latter half of the 17th century, the Europeans were gaining an upper hand.

This was because the Europeans were successful in creating superior military technology, which set them apart from others.

Although gunpowder and cannons were invented by other civilizations, Europeans improved and enhanced them. They also worked towards creating more powerful variations.

The Ottomans and the Chinese invented this technology, but they didn't feel the need to improve. There was not much of a threat which forced them to innovate and better those weapons like before. When they were weak, they innovated and improved, but once they had become mighty, they stopped.

But due to the competitive climate in Europe, improvement was a matter of survival. They improved the grain quality of the gunpowder they used, they changed the materials of the weaponry to make them lighter and more powerful.

In their shipbuilding large strides were taken also. They learned how to build big, sturdy ships for the rough Atlantic waters. Then, they learned how to equip these ships with powerful cannons for destructive potential.

And it was these new ships and weaponry that would soon allow them to travel across the whole world and conquer territories in other continents.

All this innovation allowed the Europeans to soon supersede the Eastern empires, and for the age of colonialism to soon begin.

Colonialism

With their powerful ships in tow, Europe started venturing outside of its continental borders.

Using the long-range capabilities of the new ships, they controlled ocean trade routes and demonstrated their powerful cannons by bombarding resisting coastal settlements.

The Portuguese and Spanish were the first to explore. The Portuguese dominated the spice trade with powerful ships. Additionally, they carved out an empire stretching from Aden, to Goa, and to Malacca.

The Spanish, in turn, went West into the New World and quickly overcame the comparatively primitive populations of South America in a matter of a few short years. And as a result of their successes, they sent home silver, furs, sugar, hides, etc.

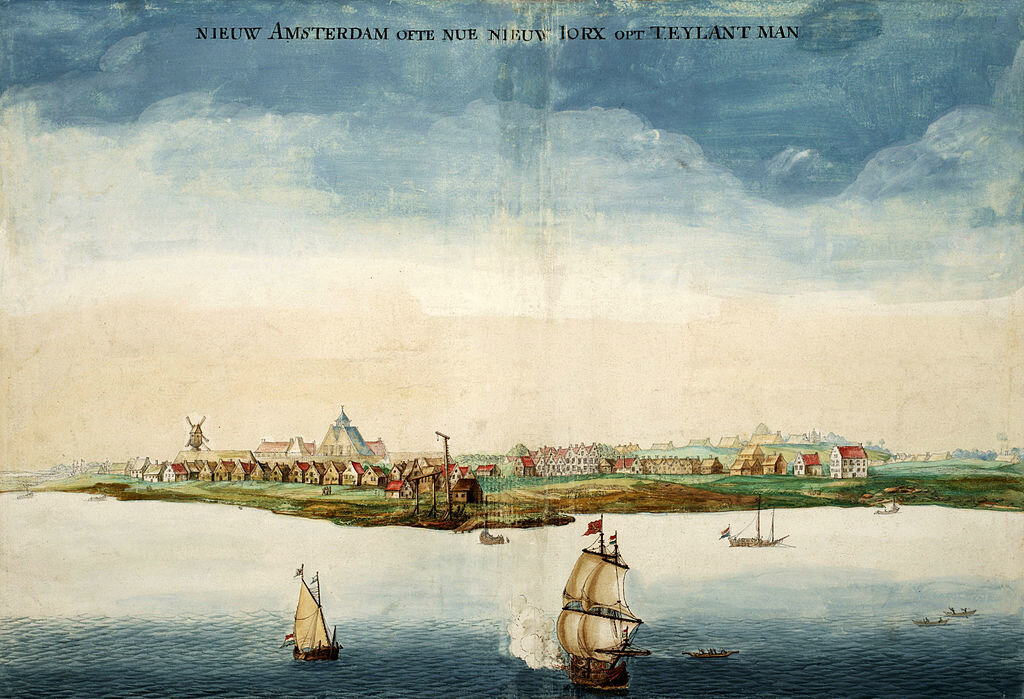

Soon the Dutch, the English, and the French joined in as the Europeans kicked off their bid for world domination.

New crops such as potatoes and maize, along with various meats gave the Europe steady nutrition. And access to the Newfoundland fisheries by the English gave Europe steady access to fish and seafood.

Whale oil and seal oil, found in the Atlantic, brought fuel for illumination.

Moreover, Russia’s eastward expansion also brought other previously inaccessible such as hemp, salts, and grains.

All of this created what is now known as the ‘modern world system’ which allowed Europe to connect the world using their new technologies and exploit various opportunities across the globe in a manner never done so before.

Less Obstacles

What allowed the Europeans to achieve this success was that they simply had fewer hindrances.

It was not that there was something special about them. Rather it was that the necessary conditions which allowed Europe to succeed were not present elsewhere.

In China, India, and Muslim lands, there wasn't the correct mix of ingredients like in Europe. Europe had a free market, strong military, and political pluralism.

And because of this they appeared to stand still while Europe advanced to the center of the world stage.

Ilyas writes at the Journal of Warfare here.