During the seventeenth-century, almost every European polity with a warm water port tried to colonize some portion of the New World. And, despite their status as a newly independent state, the Netherlands proved no exception as they went on to colonize a part of modern-day America that includes New York. Jordan Baker explains.

You can read Jordan’s previous article on the role of Black Haitian Soldiers in the Siege of Savannah during the American Revolution here.

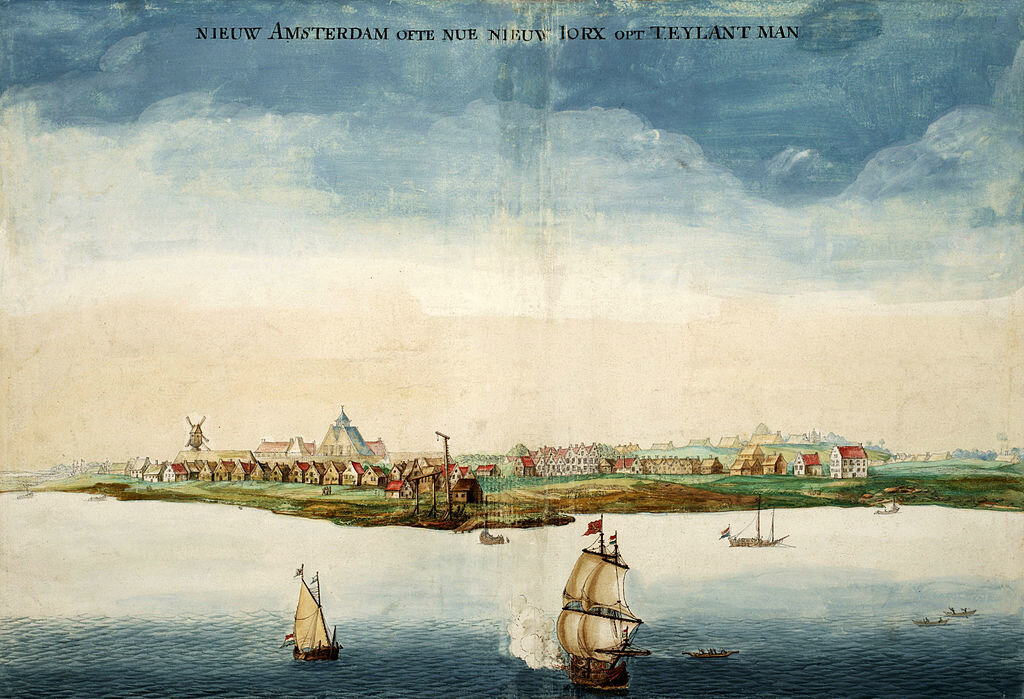

A painting of New Amsterdam (later New York) from 1664, the year the English took possession from the Dutch. By Johannes Vingboons.

Introduction

If, like me, you grew up in the United States, the history classes you took may well have given you the impression that England, Spain, and Portugal were the only European powers that attempted to colonize the Americas. This couldn’t be farther from the truth!

The Beginnings of New Netherland

The story of New Netherland starts with the beginning of the Netherlands itself. Up until 1581, the Netherlands was controlled by the Habsburg family, first under the auspices of the Holy Roman Empire, then under the Spanish crown. Beginning in 1568, however, the Dutch revolted, beginning the conflict known as both the Eighty Years’ War and the Dutch Revolt. Though the Dutch did not gain de jureindependence from Spain until 1648, they secured de factoindependence in 1581.

No longer part of the Habsburg Empire, the Dutch quickly set out making an Empire of their own. Unlike other European powers of the day, however, the Dutch Empire was based on trade rather than the acquisition of mass amounts of territory. Though Henry Hudson explored the area that became New Netherland in 1609, during the first few decades of the seventeenth-century the Dutch focused more on the Asian and African sections of their empire, capturing valuable trading ports from the Portuguese. This changed in 1621 when the Dutch Republic granted the West India Company (WIC) a charter and 24 year trading monopoly as a way to both take advantage of North American trade and challenge Spanish hegemony in the Atlantic.

Due to several factors, the European population of New Netherland remained rather low throughout the first decade of its existence. One major reason for this was the WIC’s monopoly. The controlled all trade in the colony and thus any immigrant to New Netherland was a WIC employee. And, the chances of this small population reproducing was null, as a majority of settlers brought to the area by WIC were farmers, craftsmen, hunters, and traders — all men. With Fort Orange, the Dutch were perfectly positioned to take advantage of Europeans’ growing desire for beaver pelts and they acquired these in mass trading with Iroquoian and Algonquian speaking peoples. Their settlement on Manhattan Island, New Amsterdam, also became a major Atlantic trade port, with ships arriving from all over the Americas, Caribbean, Africa, and Europe.

Attempts at Populating New Netherland: Patroonships

By 1630, New Netherland’s European population was 300. For a territory that stretched 145 miles up the Hudson from Manhattan Island, that’s pretty sparse. In order to increase their profit and population while lowering their costs, the WIC implemented the Patroonship plan. Under this plan, a settler would be given a large tract of land, thus becoming a Patroon, and were given full rights to the land and legal rights to settle non-capital court cases - almost like a manorial lord in the Middle Ages. Though the plans for Patroonship were modified after their implementation, the overall program proved successful at bringing more European settlers to New Netherland, who the WIC could then tax to make their profit.

Kiliaen van Rensselear, already a principal shareholder in the WIC, became the most successful of the Patroons, establishing Rensselaerswyck near the Dutch settlement of Fort Orange. Under this Patroonship, Rensselear controlled the largest fur trading territory in New Netherland, taking advantage of his new found ability to deal with the neighboring New England colonies and Native Nations.

While the Patroonship model for colonization did help increase the numbers of Europeans immigrating to New Netherland, most of the people making the journey weren’t Dutch. Many colonists in New Netherland were actually Walloons - French speakers from what is now southern Belgium. In fact, colonists from Wallonia became the first permanent settlers in New Netherland.

By the time the Dutch Republic ceded New Netherland to England in 1664, the colony boasted a diverse population of Swedes, Finns, Germans, English, Walloon Belgians, and Dutch, whose numbers topped out somewhere around 9,000.

The Final Years of New Netherland

The end of New Netherland began in another hemisphere altogether. The Dutch established a powerful, world-wide trading empire in the seventeenth-century, but their territories in the Western Hemisphere proved difficult to maintain. From 1630-1654, the Dutch and WIC controlled part of Portuguese Brazil, which they called New Holland. After Portugal regained independence from Spain in 1640, Brazilian planters began rebelling against their Dutch rulers. Eventually, the Dutch and WIC were forced to concede their Brazilian territory to Portugal.

Many of the colonists from New Holland made their way to other Dutch colonies in the Americas, like New Netherland. This collapse of New Holland caused the population of New Netherland to grow dramatically, helping reach the numbers mentioned earlier. A year after losing the rich sugar producing territory of New Holland, the Dutch gained control of New Sweden, a stretch of small colonies located primarily in Delaware, which lead to the incorporation of many of the Swedish and Finnish inhabitants of New Netherland.

Despite its growth in both population and territory, however, New Netherland wasn’t long for the world. The Netherlands ceded control of the colony to England in 1654. Though the Dutch did briefly regain control in 1673-1674, the territory was ostensibly English until the Treaty of Paris ended the American Revolution in 1783. Once in control, the colony’s new rulers changed the name of Fort Orange to Albany and the booming trading port on Manhattan Island from New Amsterdam to New York.

Jordan Baker writes at the East India Blogging Company here. On the site, he has recently written about the purchase of Manhattan here.

Sources

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dutch_Revolt

http://www.nysl.nysed.gov/newnetherland/what.htm

https://coins.nd.edu/ColCoin/ColCoinIntros/NNHistory.html

https://www.dec.ny.gov/docs/remediation_hudson_pdf/hrmilesmap.pdf

https://coins.nd.edu/ColCoin/ColCoinIntros/NNHistory.html

http://www.nysl.nysed.gov/newnetherland/what.html