In 1915 American industrialist and business magnate Henry Ford launched an amateur peace delegation aimed at stopping the First World War raging across Europe. Although it turned out to be disaster rand subject to ridicule, the mission offers an important example of the unorthodox ways in which private citizens have sought to broker peace.

Felix Debieux explains.

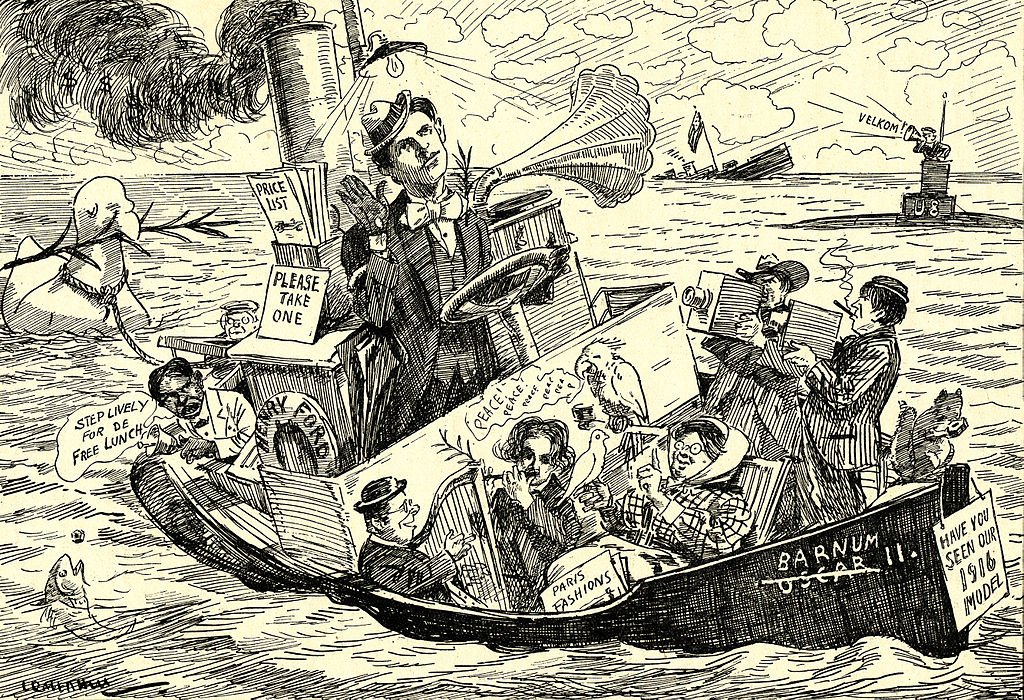

A December 1915 Punch cartoon "The Tug of Peace". It ridicules Ford’s peace mission to Europe.

When we think about ‘diplomacy’, a number of images spring to mind. Official-looking statesmen in grey suits, facing off across long tables as they discuss the terms of treaties, ceasefires and trade. This image is a narrow one, and places a great deal of importance on the work of nation states. We might call this ‘Track One’ diplomacy, that is to say the kind of diplomacy conducted in official forums by professional diplomats. There is, however, a second track. Indeed, ‘Track Two’ diplomacy – sometimes referred to as ‘backchannel diplomacy’ - refers to the non-governmental, informal and unofficial diplomacy of private citizens, major corporations, NGOs, religious organisations and even terrorist groups.

Easily overlooked, this second track has sought to shape major historical events – often at times where government-to-government diplomacy is perceived as inadequate, ineffective or to be failing in some way. This was certainly the case with American industrialist and business magnate Henry Ford, who in 1915 launched an amateur peace delegation aimed at stopping the First World War raging across Europe. Although it turned out to be complete disaster ridiculed mercilessly by the contemporary press, the mission offers an important example of the unorthodox ways in which private citizens have sought to broker peace.

A humanitarian industrialist

While Henry Ford’s motives for involving himself in international diplomacy have been disputed, Ford certainly held sincere pacifist sentiments and, from early 1915, had begun to condemn the war in Europe. Indeed, unlike the jingoism readily found among other automotive industrialists like Roy D. Chapin and Henry B. Joy, Ford described himself as a pacifist and aired his frustration with both the war and the profiteering associated with it. This caught the attention of two prominent peace activists, who approached Ford with an ambitious proposal: launch an amateur diplomatic mission to Europe and broker an end to the war.

The two peace activists play a crucial role in this story. The first was Hungarian author, feminist, world federalist and lecturer Rosika Schwimmer. Closely associated with a number of movements including women’s suffrage, birth control and trade unionism, Schwimmer from the very outset of the war had advocated for neutral parties to mediate a peace. In 1915, she successfully persuaded the International Congress of Women at The Hague to support the policy. Her companion was Louis P. Lochner, a young American who had acted as secretary of the International Federation of Students. In 1914, Lochner had been appointed as Executive Director of the Chicago-based Emergency Peace Federation, and – like Schwimmer – called for neutral nations to mediate an end to the war. Both were fervent champions for world peace, and they hoped to persuade Ford to throw his resources behind their proposal.

While their eventual meeting with Ford was a success, the proposal put to the industrialist was not entirely honest. Indeed, Schwimmer claimed to possess key diplomatic correspondence which proved that there were neutral and belligerent nations receptive to her idea of mediation. The documents, however, cannot be described as anything other than a complete fabrication. Nevertheless, they were enough to persuade Ford that there was appetite in Europe for negotiations and so he agreed to finance a peace mission. “Well, let’s start”, he said. “What do you want me to do”?

Chartering a mission to Europe

With Ford sold on the idea of neutral mediation, Lochner suggested that they seek the endorsement of President Wilson. The President could establish an official commission abroad until Congress made an appropriation. If this ‘Track One’ diplomatic route was to fail, Lochner explained, then the President could back an unofficial mission to undertake the work. Ford supported the idea, and seemed excited at the promise of good publicity. Indeed, the industrialist revealed a natural flair for epigram, thinking up such pithy pronouncements as: “men sitting around a table, not men dying in a trench, will finally settle the differences”.

On November 21, 1915, Ford, Schwimmer and Lochner lunched with a group of fellow pacifists. Everybody in attendance approved the plan of sending an official ‘Track One’ mediating mission to Europe and, if that failed, a private ‘Track Two’ delegation. To set the plan in motion, Ford and Lochner would travel to Washington to secure President Wilson’s backing. Possibly jesting, Lochner suggested to the group “why not a special ship to take the delegates over [to Europe]?” Ford immediately jumped at the idea. While some members of the group thought it ridiculously flamboyant, Ford liked the idea for that very reason. Almost immediately he contacted various steamship companies and, posing as “Mr. Henry,” asked what it might cost to charter a vessel. In no time at all, Ford had chartered the Scandinavian-American liner Oscar II.

The very next day, Ford and Lochner arrived in Washington for an appointment with the President. The meeting began well enough, with Lochner observing how “Mr. Ford slipped unceremoniously into an armchair, and during most of the interview had his left leg hanging over the arm of the chair and swinging back and forth”. After exchanging pleasantries, Ford outlined the mission, offered to finance it, and urged the President to establish a neutral commission. While he approved of the principle of continuing mediation, the President explained that he could not anchor himself to any one project and, regretfully, that he could not support Ford’s plan. This was not what Ford had prepared himself to hear. He explained that he had already chartered the ship, and had promised the press an announcement on the following day. “If you feel you can’t act, I will”, he said. While Wilson did not budge from his initial position, this was not enough to deter Ford. “He’s a small man”, Ford said to Lochner as they left the meeting. An unofficial, ‘Track Two’ mission this was going to be.

Casting a net

Eager reporters began to arrive at Ford’s hotel. The industrialist opened his press announcement with a simple question: “A man should always try to do the greatest good to the greatest number, shouldn’t he?” He continued: “We’re going to try to get the boys out of the trenches before Christmas. I’ve chartered a ship, and some of us are going to Europe”. When pressed for more detail about the voyage, Ford explained that he was going to bring together “the biggest and most influential peace advocates in the country”. Some of the heavyweights he listed included Jane Adams, John Wanamaker, and Thomas Edison.

The voyage, unsurprisingly, made front page news in both New York and around the country. While it is not clear what kind of coverage Ford expected, the reaction he did receive was generally derisive. Among his harshest critics was the Tribune, which ran with the headline:

GREAT WAR ENDS

CHRISTMAS DAY

FORD TO STOP IT

Other commentaries were more direct in their criticism. The New York Herald, for instance, described the mission as “one of the cruellest jokes of the century”. This was echoed by the Hartford Courant, which remarked that “Henry Ford’s latest performance is getting abundant criticism and seems entitled to all it gets”. Usually more sympathetic towards Ford, the World deemed the mission an “impossible effort to establish an inopportune peace.”

Ridiculed though it was, the mission – even before setting sail – was at least generating the kind of publicity which Ford craved. This, however, only disguised the huge logistical problems which the organisers of the project faced. Indeed, having announced 4th December as the date of embarkation, Ford had left only nine days to assemble an entire delegation. This was not only unrealistic, but also put the project on the back foot from the very outset.

Wasting no time in racing towards an impossible deadline, invitations were sent out at once to prospective delegates. The general response provided only further ammunition for the jeering press. Indeed, within just one day of Ford’s press announcement, John Wanamaker and Thomas Edison clarified that they would not be joining the voyage. While Jane Addams confirmed that she, at least, did plan on joining, it was hard to ignore the avalanche of refusals. These included distinguished figures such as William Dean Howells, William Jennings Bryan, Colonel E. M. House, Cardinal Gibbons, William Howard Taft, Louis Brandeis, Morris Hillquit, and many others who would have lent their credibility to the project.

Nevertheless, the net was cast wide enough that some notable peace activists were able to join. Leading suffragette Inez Milholland and publisher Samuel Sidney McClure signed up for the mission, along with more than forty reporters. Also committing to the cause was the Reverend Samuel S. Marquis, a close friend of Ford’s. In the end, the delegation was as large and distinguished as Ford could reasonably expect to assemble within such a tight timeframe. Indeed, the fact that so many were willing to abandon their commitments with only nine days’ notice, in some cases at their own expense, pointed to the prestige and appeal which they believed the mission carried.

All aboard!

The Oscar II set sail from Hoboken, New Jersey on December 4, 1915. Much to the delight of the press, arrangements began to unravel just days before embarkation. On December 1, Jane Addams – one of the mission’s key delegates – fell unexpectedly ill and had to pull out of the voyage. This was a major blow, and no doubt undermined the leadership of the expedition. It was not enough, however, to deter a crowd of roughly 15,000 people from gathering to watch the Oscar II leave the dock. As the band started to play “I Didn’t Raise My Boy to Be a Soldier”, Ford appeared and was met with resounding cheers.

There was certainly no shortage of entertainment to occupy the press. Indeed, just before the ship's departure, a prankster placed a cage containing two squirrels on the gangplank. An accompanying sign read "To the Good Ship Nutty". This was followed by a man who leapt into the water, and proceeded to swim after the ship as it left the dock. Once hauled ashore, he declared that he was “Mr. Zero” and explained that he was “swimming to reach public opinion.” Oblivious to the commotion, the crowd continued to wave and cheer. This clearly made an impression on Ford. As Lochner observed:

“Again and again he bowed, his face wreathed in smiles that gave it a beatific expression. The magnitude of the demonstration—many a strong man there was who struggled in vain against tears born of deep emotion—quite astonished and overwhelmed him. I felt then that he considered himself amply repaid for all the ridicule heaped upon him.”

As the Oscar II faded out of sight, Americans waited to see what effect she might have.

What nobody foresaw was just how soon the delegation would descend into squabbling and infighting. Much of this was triggered by President Wilson’s 7th December address to Congress, in which the case was made for military prepardness and an increase in the size of the US army. This proved to be an incendiary development, with the activists simply unable to agree on their collective response. Indeed, some aboard the Oscar II felt very strongly that the delegation should deprecate preparedness and call for immediate disarmament. Others, however, would not countenance criticism of either the President nor Congress. McClure made his position quite clear:

“For years I have been working for international disarmament. I have visited the capitals of Europe time and time again in its behalf. But I cannot impugn the course laid out by the President of the United States and supported by my newspaper”.

While some among the delegation understood this position, there were those on the voyage who were not so tolerant. Schwimmer, for instance, accused McClure of corrupting the delegation. Lochner went further still, asserting that supporters of preparedness who had joined the voyage must have simply come along for the “free ride”. Such comments only served to stoke disunity, and were lapped up by the ship’s reporters who narrated the infighting in day-to-day stories. “The dove of peace has taken flight,” cried the Chicago Tribune, “chased off by the screaming eagle”. Such reports were accused of having magnified the dispute. “The amount of wrangling has been picturesquely exaggerated,” wrote the activist Mary Alden Hopkins. “A man does not become a saint by stepping on a peace boat.”

While himself strongly opposed to preparedness in any form, it was in the end left up to Ford to patch things up. For him, the success of the voyage was paramount and, if that meant working alongside peace-lovers who supported a degree of preparedness, then so be it. Ford signed a statement, which outlined what he saw as the incompatibility between peace and prepardness but – more importantly – emphasised that all delegates on the mission were welcome. The damage, however, was already done. Indeed, delegates were very aware that their closely-held principles were being savaged in the press. “The expedition has been hampered at every step by the direct and indirect influence of the American press, by the Atlantic seaboard press,” declared one of the passengers.

As the Oscar II continued to steam across the Atlantic, the situation aboard went from bad to worse. An outbreak of influenza spread through the ship, resulting in one person dying and many others falling sick. Ford also fell ill, and retreated to his cabin in hopes of avoiding reporters. This led to a rumour that he might have secretly died, and so a group of the ship’s less considerate reporters forced their way into his quarters to check on the veracity of the story. At the same time, reporters had become highly suspicious of Schwimmer and the diplomatic correspondence she claimed to possess. After some negotiation, Schwimmer agreed to show her evidence but, angered by their comments, cancelled the exhibit. The Hungarian expressed her frustration by locking the reporters out of the Oscar II’s wireless room. By this point the group looked desperately forward to their planned arrival in Norway, where they had been promised a grand welcoming party. Like many other aspects of the mission, however, their expectations were not realised.

Land ahoy!

In the early hours of December 18, the Oscar II docked in Oslo. A handful of Norwegians came by later that morning to welcome the delegation, but this was nothing like the rousing welcome they had been promised. The reception was in fact much cooler, with many Norwegians generally supportive of military preparedness and sceptical towards the mission – particularly Schwimmer. Indeed, Norwegians felt that it was inappropriate for a citizen of a belligerent power to play a leadership role in the peace mission of a neutral country. Further still, Norwegians were generally pro-Ally and believed that peace could only be attained after Germany’s military strength had worsened. Onlookers were surely disappointed when a very sick Ford, who insisted on walking from the dock to his hotel, collapsed and went to bed. The most distinguished member of the delegation would make no further public appearances while in Norway.

Regretfully, Ford’s health showed no signs of improvement. He “was practically incomunicado”, recalled Lochner, who suspected that Ford’s friend, Samuel Marquis, was trying to talk the industrialist into returning to America. “Guess I had better go home to mother”, Ford eventually said to Lochner, “you’ve got this thing started now and can get along without me.” Lochner strongly objected, believing that Ford’s presence was critical to the success of the mission. This was to no avail, and on December 23 Ford began his long journey back to the US.

The effect this had on the rest of the delegation is rather predictable. Some felt depressed, disheartened and perhaps even a sense of betrayal. Lochner attempted to re-motivate the group: “before leaving, [Ford] expressed to me his absolute faith in the party and… the earnest hope that all would continue to co-operate to the closest degree in bringing about the desired results which had been so close to his heart—the accomplishment of universal peace”. While certainly commendable, Lochner’s efforts to soften the blow fell short. After all, everybody knew that Ford was the only one among them who commanded the stature needed to impress and energise the representatives of neutral nations. Though he continued to support the mission both morally and financially, the activists who Ford left behind inevitably splintered further apart. Nevertheless, the disjointed delegation was able to claim one success: the establishment of the Neutral Conference for Continuous Mediation.

Held in Stockholm, the Conference - attended by representatives from the US, Denmark, Holland, Norway, Sweden, and Switzerland - sought to encourage neutral governments to mediate an end to the war. On May 18, 1916, the Conference issued a manifesto asking belligerent nations to participate. The manifesto laid out three general activities: mediation between belligerents, propaganda to build public support for peace, and scientific study of the political problems. The Conference even managed to meet with the Danish Secretary of Foreign Affairs, its first formal recognition by a European government. Ultimately, however, there were no further successes that the activists could point to. Indeed, their quick work to develop a program failed to gain traction in the parliaments of the neutral nations; no action at all was taken by any of the targeted governments. By March 1, 1917, with the US moving closer to entering the war, Ford made the decision to discontinue the Conference. The total bill for the peace mission? Half a million dollars - $10,100,000 in 2022.

A total failure?

How should we evaluate the peace mission? Former US Senator Chauncey M. Depew famously reflected that “in uselessness and absurdity” the peace mission stood “without equal”. This, perhaps, is the easiest assessment of the delegation’s efforts. Indeed, without ever agreeing on how they intended to achieve peace, the group failed to persuade any neutral nation to adopt a policy of mediation. In the process, those who boarded the Oscar II were subjected to relentless ridicule and criticism. This was always about more than bruised egos, with some believing that the ridiculousness of the mission risked the credibility of their deeply-held principles. The Baltimore Sun, for instance, judged that "all the amateur efforts of altruistic and notoriety-seeking millionaires only make matters worse".

Nevertheless, Ford himself asserted that the peace ship was a success. It "got people thinking” about peace on both sides of the Atlantic, he claimed, and “when you get them to think they will think right”. Was he hurt by the level of ridicule he was subjected to? It is impossible to say, but he later reminded people that at a time when no serious effort was made to bring the war to an end, he stood up and acted. “I wanted to see peace. I at least tried to bring it about. Most men did not even try”. Ford’s positive assessment of the peace mission was surely influenced by its commercial outcomes. Tellingly, he described the expedition as the “best free advertising I ever got”.

Indeed, Ford was very much attuned to the commercial benefits of a highly publicised journey to Europe. Lochner, in fact, concluded that publicity was the only definite part of Ford’s thinking. “If we had tried to break in cold into the European market after the war, it would have cost us $10,000,000. The Peace Ship cost one-twentieth of that and made Ford a household word all over the continent”. While for the activists peace was everything, for Ford this was also an investment - an opportunity to advertise his benevolent character across Europe and America. After the war, Ford would go on to become the largest manufacturer of Liberty Motors for aircraft, blurring the boundaries he had once set between profiteering and pacifism.

A rounded assessment of the peace ship would not be complete without considering its long-term impact. Indeed, it should be remembered that ideas stimulated during the mission eventually wound up in President Wilson’s Fourteen Points, a statement of principles for peace to be used in negotiations to end the war. Notably, the list included a commitment to transparent peace treaties, free from the greedy tentacles of private deals struck on the side. This was an idea thought up by activists who had participated in the peace mission. Though they might have failed to bring an end to the war, these ‘Track Two’ citizen diplomats can claim a legacy of sorts, pioneering alternative modes of peace-building less dependent on government leadership.

What do you think of the ‘Ship of Fools’? Let us know below.

Now read Felix’s article on Henry Ford’s calamitous utopia in Brazil: Fordlandia here.

References

Open War Aboard the “Peace Ship", J. Mark Powell.

The Peculiar Case of Henry Ford, The University of Michigan and the Great War.

Henry Ford And His Peace Ship, American Heritage, Volume 9, Issue 2, February 1958.

The “Peace Ship”: An Early Attempt at Citizen Diplomacy, Read the Spirit.

The Peace Ship: Henry Ford’s Pacifist Adventure in the First World War, Barbara Kraft, New York, 1978.

The Odyssey of Henry Ford and the Great Peace Ship, Burnet Hershey, New York, 1967.

Second Track / Citizens' Diplomacy: Concepts and Techniques for Conflict Transformation, John Davies, Edward Kaufman, eds., Maryland, 2002.