S M Sigerson, author of "The Assassination of Michael Collins: What Happened at Béal na mBláth?" continues to re-examine a number of myths which have distorted the facts about Collins. Some have argued that he was merely one of several ambitious men, vying for power at the time. But does that adequately explain his role in Irish history, his legendary stature, or his undying fascination?

The previous articles in this series are here on four myths related to Collins’ death and here on another myth.

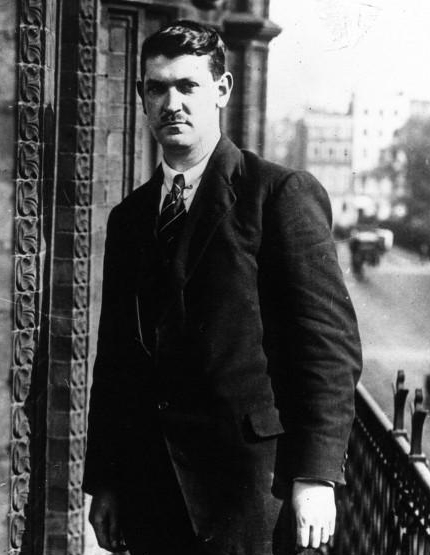

Michael Collins giving a speech. Source: Cork Film Archive, site here.

One argument that has been put forward to explain away the phenomenon of Michael Collins is the contention that he was merely one of several ambitious men of the time. Some suggest that he was distinguished only by his failure to survive, by being less successful than others.

History always involves debate. In Collins' case, the controversy which ended his life is not altogether a thing of the past, but rages on in Ireland today. Therefore writers on this topic are particularly liable to favour either himself or his political opponents.

This and other trivializations of Collins is often found in the mouths of DeValera eulogists. If translated from subliminal nuance into the plainest language possible, perhaps it might read something like: "Collins' death didn't matter. Nothing would have been better had he lived. Collins just wasn't as successful as others. Collins was a loser."

Is there a political agenda detectable, in thus waving aside the achievements of the only leader to see the British Army off Irish soil, in seven centuries of trying?

If Mr. DeValera can by reason and argument induce the people of Ireland to entrust the Nation's fortunes to him and his party ... in that event the duty of the Army, no matter what were their individual views, would be to support Mr DeValera's government, and I would exhort the people to support that government, as a government, even if I were in political opposition...

Progressive campaigning often turns on convincing people that (1) change is possible and (2) the candidate / party is different from the establishment, and will make change happen. For the same reason, these two principles are often targeted by entrenched political establishments. It becomes, in a sense, their job (if they want to keep their jobs) to convince the public that change is not going to happen. It is in their interests to encourage a general disbelief that any politician is going to be different. A general hopelessness that anything can change is advantageous to the status quo. Such inertia keeps people away from the polls: they don't bother to vote. This is good for entrenched establishments. The fewer people that vote, the more likely that the usual suspects will keep their seats. Large voter turn-outs are often good news for progressives and bad news for conservatives. When the public perceives a chance for positive improvements, when a candidate stands out as offering something genuinely valuable and innovative, when the public imagination is fired: then they stand up to be counted. It is therefore definitely in the interests of some political elements to discourage this sort of thing.

Assassination

Government by assassination is the most extreme form of that strategy. It is one very destructive and dangerous way to make sure that there will be only one kind of candidate.

Obviously, if this were a mere question of struggle between two equally selfish and unethical men, it is not Michael Collins who would have been assassinated. If he could wipe out virtually the entire British secret service in Dublin in one day, there was no one in Ireland likely to outdo him in that department.

... while it was perfectly justifiable for any body of Irishmen, no matter how small, to rise up and make a stand against their country's enemy, it is not justifiable for a minority to oppose the wishes of the majority of their own countrymen, except by constitutional means.

Collins never said it was “necessary to shoot men like" Liam Lynch or Rory O'Connor. Nor did he ever call on the public to wade through the blood of anti-Treaty leaders. He never advocated firing on comrades as a solution to the Dáil / Army split. On the contrary, he resisted doing so longer than anyone else in a comparably responsible position (although no one's position at the time can really be compared with his).

The solution he consistently sought was a just and amicable reunification of all factions. The analysis he repeatedly emphasized was the danger of dividing the country's strength, in the presence of their traditional foe at this volatile juncture. History has justified him.

Collins clearly declared that, while he had no problem with assassination as a weapon of war against a violent foreign occupation force, he did not believe in it as a form of government. That, apparently, is how he differed from his opponents. Tragically for us, he paid the supreme price for that difference.

Did you find this article interesting? If so, tell the world! Tweet about it, like it or share it by clicking on one of the buttons below!

Portions of this article are excerpted from "The Assassination of Michael Collins: What Happened At Béal na mBláth?" by S M Sigerson. Available online at www.amazon.com/dp/1493784714 or www.smashwords.com/books/view/433954. Alternatively, ask at your local bookstore.