Every October for the past 52 years, the International Hot Air Balloon Festival takes place in Albuquerque, New Mexico. This event is the world's largest hot air balloon festival, with over 500 hot air balloons and nearly 1 million people in attendance. The hot air balloon made its first American flight in 1793, yet it still captures our attention and imagination. So, what is the history behind these magnificent flying balloons?

Angie Grandstaff explains.

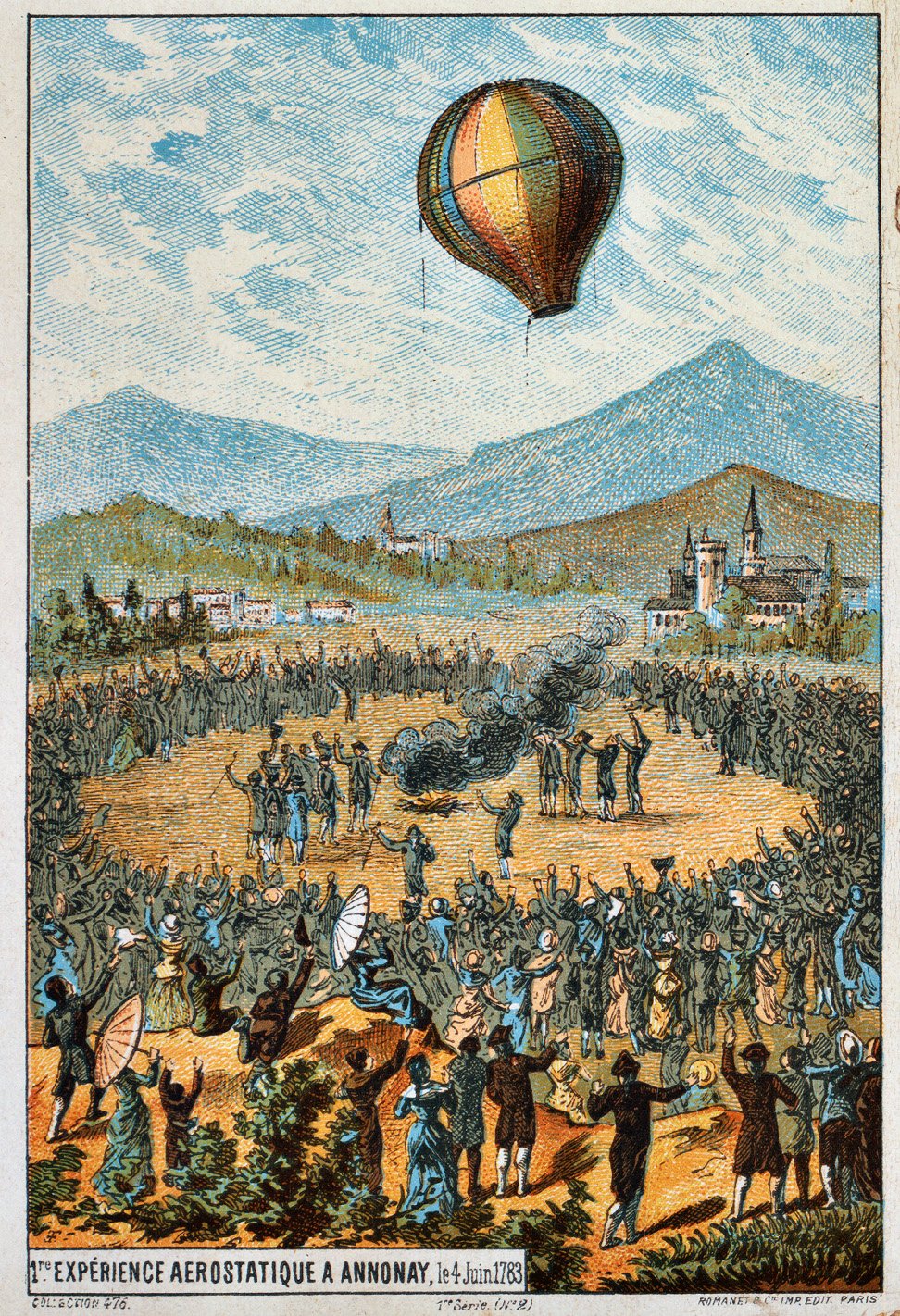

A depiction of an early balloon flight in Annonay, France in 1783.

The Origins of Hot Air Balloons

The idea of flying is something that humans have fantasized about for centuries. Many have theorized about how this could happen. English philosopher Roger Bacon hypothesized in the 13th century that man could fly if attached to a large hollow ball of copper filled with liquid fire or air. Many dreamed of similar ideas, but it wasn’t until 1783 that the dream became a reality.

French brothers Joseph-Michel and Jacques-Etienne Montgolfier were paper manufacturers who observed that a paper bag would rise if hot air was put inside it. Many successful experiments proved their theory. The Montgolfier brothers were to demonstrate their flying balloon to King Louis XVI in September 1783. They enlisted the help of a famous wallpaper manufacturer, Jean Baptiste Réveillon, to help with the balloon design. The balloon was made of taffeta and coated with alum for fireproofing. It was 30 feet in diameter and decorated with zodiac signs and suns in honor of the King.

A crowd of 130,000 people, including King Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette, watched the Montgolfier brothers place a sheep, rooster, and duck in a basket beneath the balloon. The balloon floated for two miles and was safely returned to the ground with the animals unharmed. This successful flight showed what was possible, and they began planning a manned trip into the sky.

There was much concern about what the high altitude may do to a human, so King Louis XVI offered a condemned prisoner to be the first to fly. But Jean-Francois Pilatre de Rozier, a chemistry and physics teacher, asked and was granted the opportunity to be the first. The Montgolfier brothers sent de Rozier into the sky on several occasions. Benjamin Franklin, the Ambassador to France at the time, witnessed their November 1783 flight. Franklin wrote home about what he saw, bringing the idea of hot air balloons to American visionaries.

An American Over the English Channel

Advances were being made with different fabrics and gases, including hydrogen, to keep the balloon aloft. Many brave individuals were heading into the skies. Boston-born Dr. John Jeffries was eager to fly. Jeffries offered to fund French inventor Jean-Pierre Blanchard’s hot air balloon expedition to cross the English Channel if he was allowed a seat. Dr. Jeffries was a medical man interested in meteorology, so this trip into the clouds fascinated him.

The two men headed into the air from the cliffs of Dover, England in January 1785. Blanchard’s gear and a boat-shaped gondola carrying him and Jeffries weighed down the hydrogen-filled balloon. The balloon struggled with the weight as it headed across the channel, so much so that they had to throw everything overboard. Their desperation to stay in the air even led them to throw the clothes on their backs overboard. The pair landed safely in France minus their trousers but were greeted by locals who thankfully clothed them.

First Flight in America

Blanchard’s groundbreaking achievements in Europe brought him to America in 1793. He offered tickets to watch the first manned, untethered hot air balloon flight. The first flight was launched from the Walnut Street Prison yard in Philadelphia. George Washington was in attendance with other future presidents, such as Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, James Madison, and James Monroe. Blanchard, who did not speak English, was given a passport by Washington to ensure safe passage wherever he landed. Blanchard ascended 5,800 feet into the air and landed 15 miles away in Deptford, New Jersey.

Europe dominated the field of aeronautics, but Blanchard’s first American flight demonstrated the possibilities of flight to America and its leaders. It inspired American inventors and explorers to take to the skies. It was a significant step in the global progress of aviation. An interesting side note about Blanchard: his wife Sophie was also an avid balloonist, a woman ahead of her time. They both died in separate ballooning accidents.

Early American Balloonists

The Montgolfier brothers' ballooning adventures led to balloon madness in America. There was much interest in the science of flying balloons as well as how balloons can be used as entertainment.

Philadelphia doctor John Foulke was fascinated with the science of ballooning. He witnessed the Montgolfier brothers’ successful manned hot-air balloon flights in Paris with Benjamin Franklin. Foulke returned to his Philadelphia home and conducted experiments, sending small hot air balloons into the sky. He lectured at the University of Pennsylvania on ballooning, even inviting George Washington to one. Washington could not attend but was keenly interested in hot air balloons and saw their potential for military use. Foulke began raising funds to build America's first hot air balloon but never reached his goal.

While Foulke was lecturing about the science of ballooning and attempting to raise funds, a Bladensburg, Maryland tavern owner and lawyer, Peter Carnes, was ready to send a balloon into the air in June 1784. Carnes was a very ambitious man with an entrepreneurial spirit. He saw American’s enthusiasm for the magnificent flying balloons as a way to make money. Interestingly, Carnes had very little knowledge about how to make a balloon take flight, but against all odds, he built a balloon. His tethered unmanned balloon was sent 70 feet into the air. Carnes set up a more significant event in Baltimore, selling tickets to a balloon-mad city for a manned flight. Unfortunately, Carnes was too heavy for the balloon, but a 13-year-old boy, Edward Warren, volunteered to be the first. Warren ascended into the sky and was brought back safely to the ground, becoming the first American aviator.

Cincinnati watchmaker Richard Clayton saw ballooning as an opportunity to entertain the masses. In 1835, he sold tickets to the launch of his Star of the West balloon. This 50-foot high, hydrogen gas-fueled balloon carried Clayton and his dog. Once a mile above the city, Clayton, wanting to put on the best show for his crowd, threw his dog out of the balloon. The dog parachuted to the ground safely. Clayton’s nine-hour trip took him to present-day West Virginia. This voyage, Clayton’s Ascent, was commemorated on jugs and bandboxes, some of which are part of the Cincinnati Art Museum’s collection. Clayton traveled to many American cities with his balloons and entertained thousands. Clayton used his connections with the press to help bring in the crowds.

Thaddeus Lowe was a New Hampshire-born balloonist and inventor who was primarily self-educated. He began building balloons in the 1850s, traveling the country, giving lectures, and offering rides to paying customers. Lowe believed hot air balloons could be used for communication and was devising a plan to build a balloon that could cross the Atlantic Ocean when the Civil War began.

Balloons in the Civil War

President Lincoln was interested in finding out how flying balloons could gather intelligence for military purposes. In June 1861, Lowe was summoned to Washington D.C., where he demonstrated to President Lincoln how a balloon's view from the sky combined with telegraph technology could give the Union Army knowledge of the Confederate troop movements. President Lincoln saw how this could help his army. So, he formed the Union Army Balloon Corps. Thaddeus Lowe was the Corps' Chief Aeronaut. Lowe used a portable hydrogen gas generator that he invented for his seven balloons.

The Peninsula campaign gave Lowe his first chance to show how his balloons could contribute positively to the Union Army. In the spring of 1862, he was able to observe and relay the Confederate Army’s defensive setup during the advance on Richmond. Lowe’s aerial surveillance gave the Union Army the location of artillery and troops during the Fredericksburg campaign in 1862 and the Chancellorsville campaign in 1863.

The Balloon Corps made 3,000 flights during the Civil War. The surveillance obtained from these flights was used for map-making and communicating live reports of battles. The balloon reconnaissance allowed the Union to point their artillery in the correct direction even though they couldn’t see the enemy, which was a first. The Confederates made several attempts to destroy the balloons, but all attempts were unsuccessful. The balloons proved to be a valuable tool in war.

Unfortunately, Thaddeus Lowe faced significant challenges from Union Army leaders who questioned the cost of his balloons and his administrative skills. Lowe was placed under stricter military command, a difficult situation for him. Ultimately, Lowe resigned from his position in the Balloon Corps, and the use of balloons during battle ceased. Lowe's journey led him back to the private sector, where he eventually settled in Pasadena, California, and continued his inventive pursuits, eventually holding 200 patents.

Modern Hot Air Balloons

Hot air balloons lost their popularity as America entered the 20th century. But in the 1950s, Ed Yost set out to revive the hot air balloon industry. Yost is known as the Father of Modern Hot Air Ballooning. He saw the need for the hot air balloon to carry its own fuel, so he pioneered the use of propane to heat the inside of the balloon. Yost also created the teardrop balloon design. He experimented with balloons, including building his own, and made the first modern-day hot-air balloon flight in 1960. Yost was strapped in a chair attached to a plywood board beneath a propane-fueled balloon traveling for an hour and a half in Nebraska. His improvements made hot air balloons safer and semi-maneuverable. Yost crossed the English Channel and attempted to cross the Atlantic Ocean solo. His attempt across the Atlantic failed, but he built a balloon for Ben Abruzzo, Maxie Anderson, and Larry Newman to try again. The Double Eagle II was the first balloon to cross the Atlantic in 1978.

Yost’s achievements and those of many other American hot air balloon enthusiasts helped the sport of hot air ballooning take flight in the second half of the 20th century. Hot air balloon festivals now take place around the country year-round and are major tourist attractions. The Albuquerque International Hot Air Balloon Festival is the world's biggest hot air balloon festival. Hot air balloons have become big business for travelers who want a bird’s eye view of America.

Humans have always wanted to conquer the skies. The curiosity and ingenuity of people like the Montgolfier brothers laid the foundation for Americans to push the boundaries of aviation. The early experiments of scientists and entertainers helped 20th-century inventors and adventurers build safer hot air balloons. Today, there is a vibrant hot-air balloon culture in America. Millions of Americans celebrate the scientific milestones and the sheer joy of flight every year. The history of hot air ballooning shows us the power of imagination and dreams.

Angie Grandstaff is a writer who loves to write about history, books, and self-development.

References

https://airandspace.si.edu/stories/editorial/presidential-writings-reveal-early-interest-ballooning

https://balloonfiesta.com/Hot-Air-History

https://www.battlefields.org/learn/biographies/thaddeus-sobieski-constantine-lowe

https://fly.historicwings.com/2012/06/the-first-american-aviator/

https://ltaflightmagazine.com/the-first-aerial-crossing-of-the-english-channel/

https://www.nytimes.com/2007/06/04/us/04yost.html

https://www.space.com/16595-montgolfiers-first-balloon-flight.html

https://www.wcpo.com/news/insider/history-richard-clayton-balloon