1856 was a critical year that would change the course of history for the United States. Tensions between the North and the South had been on the rise for many decades, and the threat of civil collapse was imminent. On March 4th, 1857, James Buchanan was inaugurated as the nation's fifteenth president. At the time, Americans believed that Buchanan was the leader necessary to prevent total civil unrest and the South leaving the Union. However, Buchanan’s actions during the Utah War, Bleeding Kansas, and the Dred Scott decision failed to resolve the crisis. Many historians rate President James Buchanan as one of the worst presidents in history.

Lillian Jiang explains.

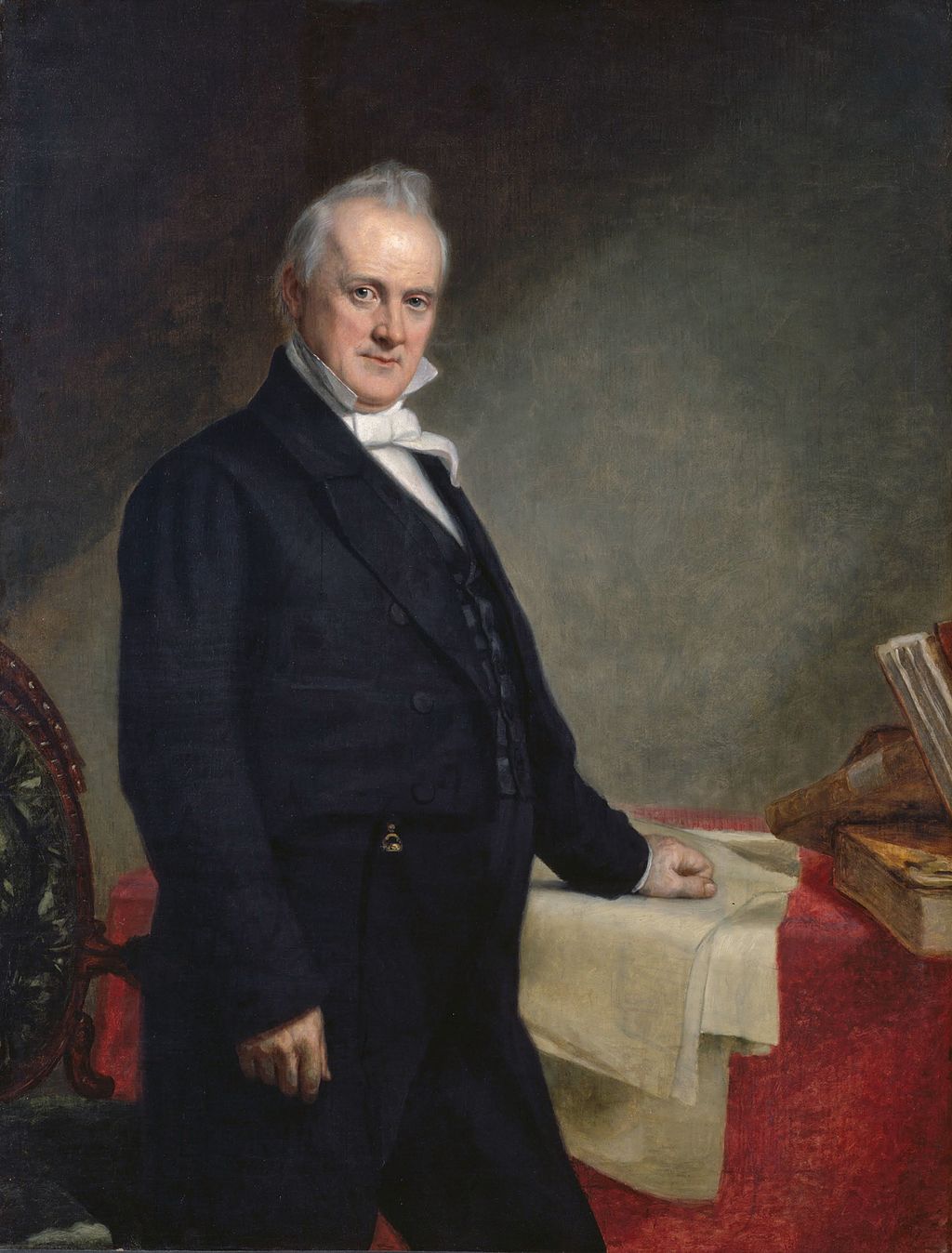

President Buchanan (center) and his cabinet.

Historians sometimes refer to the Utah War as “Buchanan’s Blunder”. In simple terms, The Utah War was an unnecessary confrontation between Mormon settlers (the members of the Church Jesus Christ of Latter-day saints in Utah) and the Armed Forces of the United States from 1857 to 1859. Mormons desired their own isolated territory, to practice freedom of religion. But many Americans and President Buchanan viewed Mormonism and the leaders of the LDS Church negatively, specifically because they practiced poligamy. Tensions between Americans and the Mormans had been growing for a long time, and when Buchanan sent an army of 2,500 troops in what he called the “Utah Expedition '', Mormans assumed that they were being persecuted and armed themselves in preparation for war.

Although no direct battles occured, Mormons feared occupation, and murdered 120 migrants at Mountain Meadows (Ellen, 1). The Utah War or the Mormon Rebellion only lasted for a single year, and congress blamed Buchanan for the unnecessary violent conflict.

President Buchanan’s friend, Thomas L. Kane, who corresponded regularly with Brigham Young, intervened, and convinced the present that all Mormons would accept peace if offered, so the president granted amnesty to all Utah residents who would accept federal authority. (Ellen, 1)

Buchanan’s approach to the crisis only left a bitter aftertaste of his administration. (Stampp, 60).

Inauguration

In the year of President Buchanan’s inauguration, the Panic of 1857 swept the nation. The Panic of 1857 was a financial crisis in the United States caused by a sudden downturn in the economy, which was a result of false banking practices and the decline of many important businesses that were central to the economy, including railroad companies. At the beginning of President Buchanan’s inauguration in 1857, the United States had “$1.3 million dollars surplus and a moderate $28.7 million debt.” (Ellen, 1) When the 16th President of the United States, Abraham Lincoln, took the presidency in 1861, the U.S. Treasury recorded a “25.2 million deficit and a 76.4 million debt… The amount of fiscal accumulated in the years was the largest imbalance by a pre-Civil War leader.” (Ellen, 1).

To ease the financial crisis, President Buchanan ordered the withdrawal of all banknotes under twenty dollars and ordered the state banks to follow the federal government’s “Independent Treasury System,” which required that “all federal funds be deposited into treasuries” (History Central, 1) instead of private banks. Although this did ease the financial crisis, the Utah War had added millions to the army’s budget (Ellen, 1). The financial crisis also had an impact on sectionalism between the North and South. As the South was not affected by the crisis as much as the North because of the prevalence of slavery, Southern states began to believe they had a far superior economy, which divided the Union even further. On this matter and Buchanan’s actions, historian Mark W. Summers said, “the most devastating proof of government abuse of power since the founding of the Republic.” (Ellen, 1)

Bleeding Kansas

One of Buchanan’s most significant missteps was in regards to the way he dealt with Bleeding Kansas, a period of violent warfare between pro and anti-slavery factions in Kansas. The Kansas-Nebraska Act, passed in May of 1854 by President Franklin Pierce, gave residents residing in Kansas Territory the right to choose whether or not to permit slavery because of Popular Sovereignty, which gave rise to violent confrontations over the legality of slavery. On December 8th, 1957, in his first annual address to Congress, President Buchanan promised to resolve the conflict. However, his future decisions would not promote a resolution between factions and instead would escalate tension and violence.

President Buchanan was careless about whether or not Kansas would become a slave state or a free state. Although Buchanan was morally opposed to slavery, he believed that it ultimately protected by the laws of the constitution. He wanted to admit Kansas into the Union as soon as possible in hopes of settling conflicts. In 1857, Buchanan demanded approval of Kansas’s Lecompton Constitution, which protected the rights of slaveholders because he was politically dependent on Southern Democrats. However, Buchanan endorsed Popular Sovereignty, so he held an election in Kansas, on January 4th, 1858, to decide whether the constitution should be rejected or ratified. The constitution was rejected by a vote of “11,300 to 1,788” (Ellen, 1). In the end, Buchanan conflicting stances on slavery did not gain approbation from neither the Northern nor Southern states.

Buchanan’s unrelenting support for the constitution and his dedication to Popular Sovereignty ultimately had a destructive impact on the Union. The rejection of the constitution angered many Southerners. The Northerners felt betrayed by Buchanan for protecting slave owners after being so vocally anti-slavery. In his inaugural address, he stated:

To their decision, in common with all good citizens, I shall cheerfully submit, whatever this may be, though it has ever been my individual opinion that under the Nebraska-Kansas act the appropriate period will be when the number of actual residents in the Territory shall justify the formation of a constitution with a view to its admission as a State into the Union (Wilder, 117).

He believed that governing the territories with Popular Sovereignty would reunite the opposing factions, but instead, it aggravated them even further.

Poor judgments

Buchanan’s poor judgments continued into the Dred Scott V. Sandford case as well. The Dred Scott case was when a formerly enslaved man, Dred Scott, sued his master for his freedom in 1846. The Northwest Ordinance of 1787 and The Missouri Compromise of 1820 both prohibited slavery in Fort Snelling—what is now present-day Minnesota—therefore, he argued that he had been illegally enslaved in a free territory. (Ellen, 1). After winning his lawsuits in a lower court, the case was handed over to the Supreme Court after eleven years. Despite the long wait, the Supreme Court’s decision did not satisfy the abolitionists. On March 6, 1857, referring to the “Dred and Harriet Scott: A Family's Struggle for Freedom”, the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, Roger B. Taney decided:

The powers over person and property of which we speak are not only not granted to Congress, but are in express terms denied. . . . And this prohibition is not confined to the States, but the words are general, and extend to the whole territory over which the Constitution gives it power to legislate, including those portions of it remaining under territorial government, as well as that covered by States. They had for more than a century before been regarded as beings of an inferior order, and altogether unfit to associate with the white race, either in social or political relations; and so far inferior, that they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect; and that the negro might justly and lawfully be reduced to slavery for his benefit. (79)

The court determined that African-Americans could not be citizens of the United States and that Congress had no power to prohibit slavery (Swain, 79). Buchanan also concurred with the decision, believing that the Constitution protected slavery. The Republicans quoted Buchanan’s inaugural address to claim that he was aware of the court’s verdict as he had addressed that he would “cheerfully submit” to the decision regarding the Dred Scott case and urged citizens to do the same (Ellen, 1).

This case is one of the most controversial Supreme Court decisions to this date. The result invalidated the Missouri Compromise and further widened the divide between North and South over slavery (Ellen, 1). In his fourth annual address, Buchanan explained that his power was restrained under the Constitution and laws. He stated:

It is beyond the power of any president, no matter what may be his own political proclivities, to restore peace and harmony among the states. Wisely limited and restrained as is his power under our Constitution and laws, he alone can accomplish but little for good or for evil on such a momentous question. (Hirschfield, 70).

His actions or rather, non-actions, towards sectionalism became the rallying point for nations to vote for Abraham Lincoln into office in 1860.

Sectionalism and slavocracy were the most contentious issues at the time. An empowered and decisive leadership was needed to settle the crisis between the North and the South, but Buchanan lacked these qualities as president. His blunders during the Utah War, Panic of 1857, Bleeding Kansas, and the Dred Scott vs. Sandford case only further raised tensions between the factions and left the U.S. in great turmoil. Although Buchanan had good intentions and was trying to prevent the outbreak of an imminent civil war, his administration failed to do so.

What do you think of President Buchanan? Let us know below.

Works Cited

Ellen, Kelly. “Everything Wrong with the Buchanan Administration.” Libertarianism.org, 12 June 2020, www.libertarianism.org/everything-wrong-presidents/everything-wrong-buchanan-administration#_edn15.

Hirschfield, Robert S.. The Power of the Presidency: Concepts and Controversy. United States, Aldine, 1982.

Pray, Bobbie, and Marilyn Irvin Holt. Kansas History, a Journal of the Central Plains: a Ten-Year Cumulative Index. Kansas State Historical Society, 1988.

Stampp, Kenneth M. And the War Came: the North and the Secession Crisis, 1860-1861. Louisiana State University Press, 1970.

Swain, Gwenyth. Dred and Harriet Scott: A Family's Struggle for Freedom. Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2010.

Wilder, Daniel Webster. The Annals of Kansas. United States, G. W. Martin, 1875.