Robert Todd Lincoln (1843-1926) was the son of Abraham Lincoln and an influential figure in his time. He was also near the scene at the time of three US presidential assassinations spanning over 35 years. Samantha Arrowsmith explains.

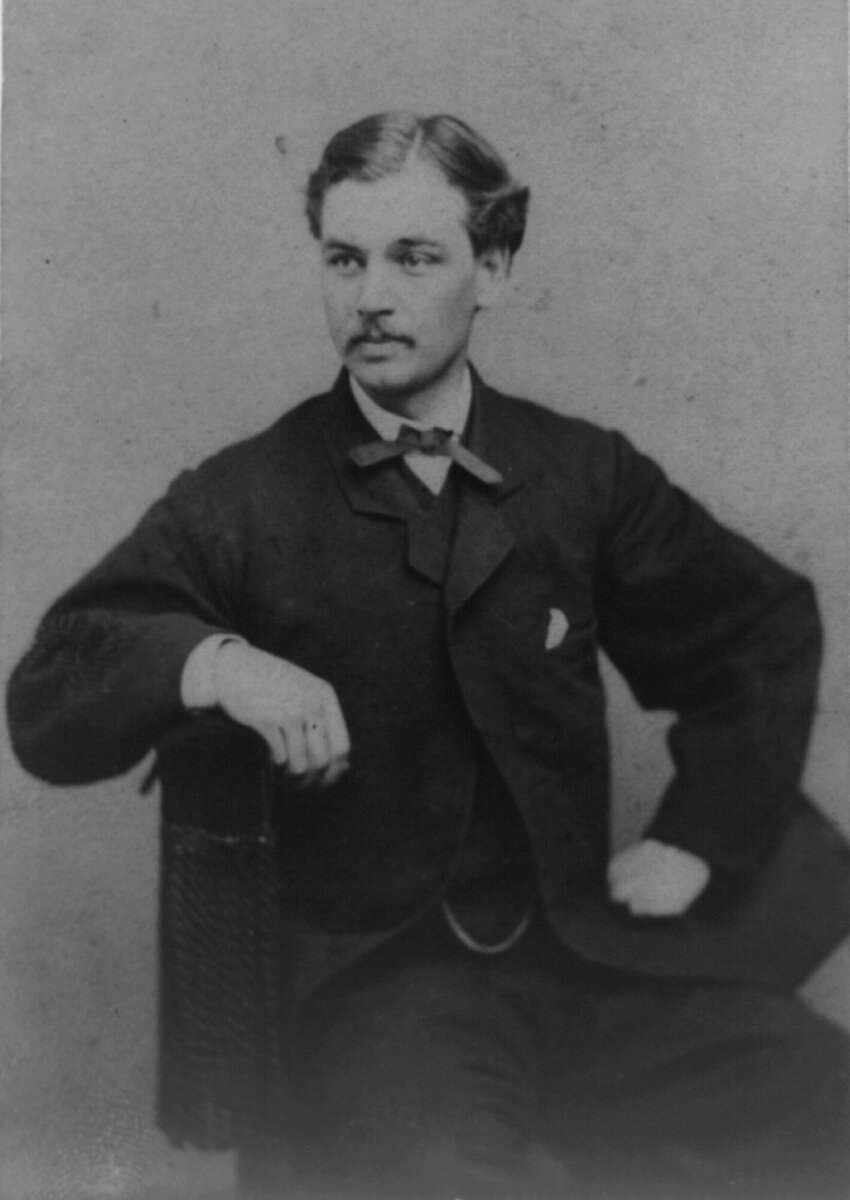

A young Robert Todd Lincoln.

There are some figures in history that transcend their time, even if we are sometimes largely ignorant of why it is that we remember them. Cleopatra, Alexander the Great, Genghis Khan, Napoleon, Abraham Lincoln, Einstein and Hitler are all names that echo down the ages, for good or ill, and who even the most history-phobic of us will recognize.

To be the child of one of these would not have been an easy place to occupy, and Robert Todd Lincoln bore the weight of that position for most of his life. He is remembered as an ‘unsympathetic bore[i]’, tainted by his relationship with his successful father and his mentally ill mother[ii]. Yet Robert carried another burden: if such a thing as a curse exists, then Robert was encumbered by one of the worst – the curse of the presidential assassination.

Abraham Lincoln: April 15, 1865

Robert’s first encounter with a presidential assassination was that of his own father, Abraham Lincoln, 16th President of the United States. It was an event touched by coincidence and regret, and one which had a profound effect on his eldest son.

Robert’s relationship with his father is considered by many historians to have been strained[iii]. As the son of an aspiring politician, Robert rarely saw his father during his childhood and their bond was undoubtedly weaker than the one Abraham had with his other sons. Yet it would be overstating their difficulties to say that Robert was estranged from his father; on the day of the assassination they had spent several hours alone together before the President went to a cabinet meeting.[iv] That evening he and his parents had dined together at the White House and he remembered some years later how his father had asked him to come to the Ford Theatre with them. Not attending was one of his greatest regrets[v]. In a 1921 article based on the recollections of Robert to a friend, he believed that:

“My seat must have been placed in the door alcove…which was covered with a curtain…He [Booth] would have encountered a psychological obstacle.…To open the door and fire at an unsuspecting man is one thing, but to fire after he had found his way blocked is another. I do not believe that he would have attempted it if I had been there.”[vi]

Despite being shot in the head by John Wilkes Booth, the President was not killed instantly and was carried to a house belonging to William Petersen where he died at 7:22am the next morning with Robert at his bedside. Despite his previous stoic behavior, The Secretary to the Navy noted that he ‘gave way on two occasions to overpowering grief and sobbed aloud…’[vii].

The event affected Robert not only as a son but also as a future government official, and one letter in particular shows how he was still conscious of the danger to the incumbent president 24 years later:

‘I have no doubt that President Arthur will take care of himself; but he is undoubtedly liable to be killed by some crazy person or by a fanatic who would be willing to do the deed for the notoriety which might be gained thereby.’[viii]

In an ironic twist of fate, Abraham Lincoln had previously had a great deal to be grateful to the Booth family for. His killer’s elder brother, the celebrated actor Edwin Booth, had saved Robert from possible injury or even death at New Jersey train station in either 1863 or 1864. Horrified by his brother’s actions, it gave Edwin comfort to know that he had been of some benefit to the Lincoln family and Robert was able to talk about the incident without any bitterness, recalling in 1918 that ‘I never again met Mr. Booth personally, but I have always had most grateful recollection of his prompt action on my behalf’.[ix]

James Garfield: September 19, 1881

Four months into his presidency, James Garfield advertised his intended plan to move to New Jersey for the summer. He would take the train from Washington’s Baltimore and Potomac railroad station on July 2, 1881 and among the members of his cabinet there to see him off would be his Secretary of War, Robert Todd Lincoln.

Up until that point the only President to have been assassinated was Lincoln’s father, so an attempt on the President was considered both a rare and somewhat unlikely event. James Garfield believed that the President should be seen by the people and he therefore took few precautions when in public. He had once written:

‘The letter of Mr. Hudson of Detroit, with your endorsement came duly to hand. I do not think there is any serious danger in the direction to which he refers - though I am receiving, what I suppose to be the usual number of threatening letters on that subject. Assassination can no more be guarded against than death by lightning; and it is not best to worry about either.’[x]

Unfortunately, Charles Guiteau had decided that the President’s death was a political necessity. His initial anger at being overlooked for a diplomatic position in Paris (which he had convinced himself was his right due to a speech he had written in support of Garfield during the election) gradually turned to paranoia. He was convinced that Garfield disliked him due to his allegiance to the Stalwart faction of the Republican Party and eventually that Garfield was a traitor and dictator.[xi] He wasn’t subtle in his intentions, going so far as to send the President letters and asking for a tour of the prison where he believed he would be incarcerated after the event.[xii] A letter taken from his pocket read:

‘The President’s tragic death was a sad necessity, but it will unite the Republican Party and save the Republic…I had no ill-will toward the President. His death was a political necessity.’[xiii]

Robert Lincoln had come to the station to let the President know that he was unable to join him on the trip as originally planned, but what he witnessed must have brought back terrible memories. Reportedly only 40 feet away from the President, he watched Guiteau step out of the shadows, walk up to the President and fire two shots, one to the arm and the other to the back. As with his father’s shooting, he showed some elements of calmness, attending the fallen President, calling for a gunshot wound specialist, Dry Bliss, and putting soldiers onto the streets to ensure calm.[xiv]

As with President Lincoln, Garfield did not die immediately; in fact, it took 80 days for him to succumb, not to the gunshot wound, but to the septicemia caused by his doctors. In September 1881, Robert Todd Lincoln attended a second funeral of an assassinated president.[xv]

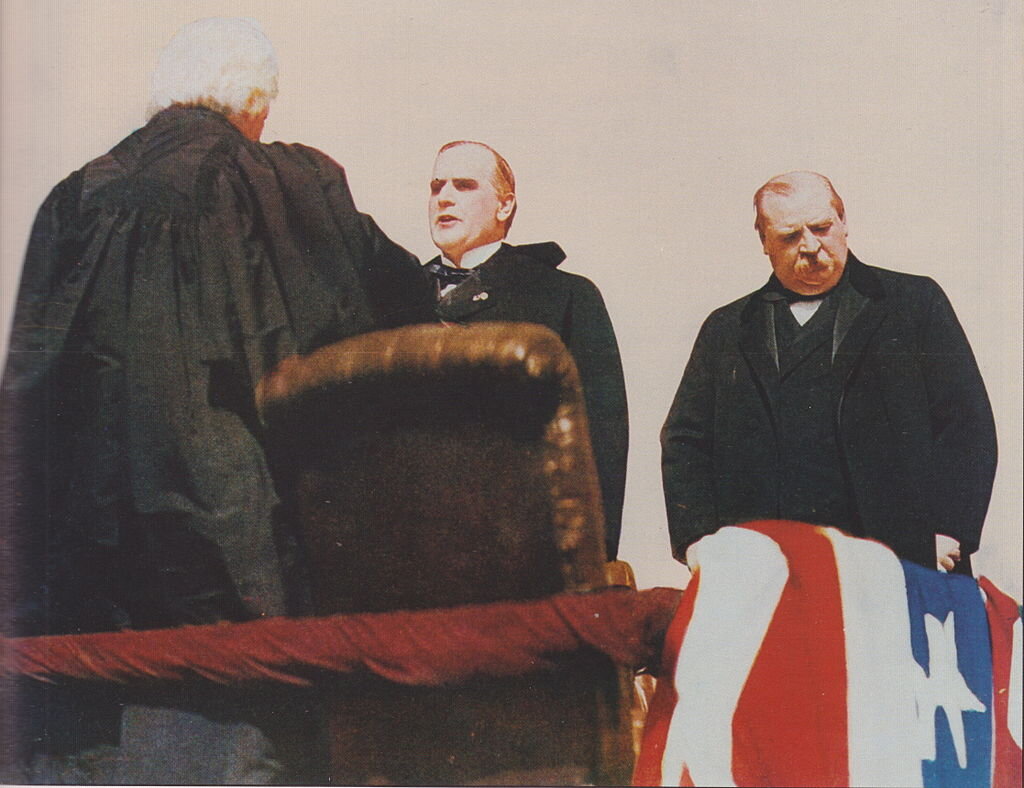

William McKinley: September 14, 1901

The Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo was intended to showcase American achievement with the slogan ‘commercial wellbeing and good understanding among the American Republics’[xvi]. President William McKinley, six months into his second term as the 25th President, was attending as part of his American tour. He was a popular president and the speech he gave there on September 5 was attended by a vast audience[xvii]. The next day, he toured Niagara Falls before returning to the fair for a public reception at the Temple of Music. McKinley enjoyed meeting the public and despite Secretary Cortelyou’s reservations, he was determined to attend, putting the reception back onto his schedule every time it was removed. Cortelyourelented but ensured that there would be ample security at the venue: the President’s own protection officer, George Foster, plus two other Secret Service Agents, the Exposition police, four Buffalo detectives and a dozen artillerymen[xviii]. But the precautions were to no avail. The day was hot and the usual precaution that everyone in the line should approach the President empty handed was abandoned, along with the habit that Foster should stand beside the President. By the time Foster realized that the approaching man, with his hand covered by a handkerchief[xix], was a danger, it was too late and at 4:07pm unemployed factory worker turned political anarchist, Leon Czolgosz, shot McKinley twice in the abdomen.

A few hours later Robert Todd Lincoln stepped off of a train at Buffalo station on his way to the Exposition to be greeted by a telegram reading:

“President McKinley was shot down by an anarchist in Buffalo this afternoon. He was hit twice in the abdomen. Condition serious.”[xx]

Lincoln missed the actual moment of the shooting, but he immediately went to see the President and spent some time with him that evening and again two days later. Lincoln believed that the President was remarkably well given what had happened to him, but eight days later on September 14, McKinley died of gangrene.

The event could only have brought back more memories for Lincoln and he did not disguise his sadness when he wrote to the new President, Theodore Roosevelt:

“I do not congratulate you, for I have seen too much of the seamy side of the Presidential Robe to think of it as an enviable garment.”[xxi]

A Certain Fatality

When Robert Lincoln died in 1926, there had been three presidential assassinations and he had a connection to them all. As historian Todd Arrington has observed, that might not have been unusual for a man involved in politics as Lincoln was[xxii], but, on a personal level, it must have been a painful situation.

‘There is a certain fatality about presidential functions when I am present,’ Lincoln is supposed to have quipped. Perhaps the more telling quote is the one he gave to the New York Times the day after the shooting of James Garfield in Washington: ‘How many hours of sorrow I have passed in this town.’[xxiii].

What do you think of Robert Todd Lincoln? Let us know below.

Now, you can read Samantha Arrowsmith’s article on 7 occasions Europe changed the time here.

[i] Lincoln: A Foreigner’s Quest, Jan Morris, 2001, p128

[ii] Meet Robert Todd Lincoln, The Estranged Son of the 16th President who had his mother committed, Lauren Zmirich, 2019

[iii] Lincoln’s Boys: The legacy of an American father and an American family, Robert P Watson and Dale Berger, 2010

[iv] Giant in the Shadows: The life of Robert T Lincoln, Jason Emerson, 2012, p99

[v] Emerson, p107

[vi] The Lincoln Financial Foundation Collection

[vii] Emerson, p105

[viii] Letter from Robert Lincoln 28 September 1881

[ix] How Edwin Booth Saved Robert Todd Lincoln’s Life, Jason Emerson, 2005

[x] Letter from President Garfield to Sherman, November 1880

[xi] Killing the President: assassinations, attempts and rumored attempts on US Commanders-in-Chief, Willard M Oliver and Nancy E Marion, 2010, p44

[xii] Oliver and Marion, p44

[xiii] The New York Times 3 July 1881

[xiv] ‘A Certain Fatality’ Robert Todd Lincoln and the Presidential Assassinations, Todd Arrington, 2014

[xv] Funeral of President Garfield: Announcement to the Public

[xvi] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pan-American_Exposition

[xvii] You can view the President giving the speech at https://www.loc.gov/item/00694342/

[xviii] JFK assassination records: Appendix 7: a brief history of presidential protection

[xix] The New York Times 7 September 1901

[xx] Arrington, 2014

[xxi] Ford’s Theatre National Historic Site

[xxii] Arrington, 2014

[xxiii] Arrington, 2014