American history has had many violent protests, and these often went on for significant periods of time. Here, Theresa Capra continues a series looking at the 2020 protests in America from an historical perspective.

In this article, she considers race-based protests in American history. She looks at how African-Americans often suffered from racist protests in the 19th and into the 20th centuries – and then considers how anti-racist protests in the 1960s and 1919 compare to those of today.

You can read the first article in the series on how 2020’s protests compare to the Bacon’s, Shays’, and Whiskey Rebellions here.

Dr. Theresa Capra is a Professor of Education who teaches education, history, and sociology at a Community College. She is the founder of Edtaps.com, which focuses on research, trends, technology, and tips for educators.

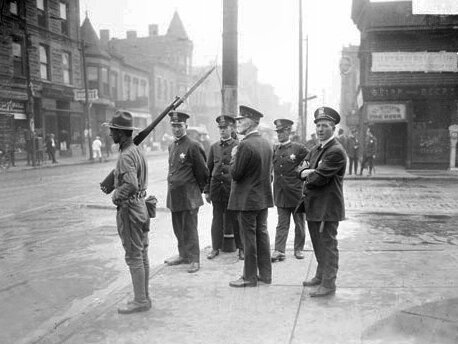

Policemen and a soldier during race riots in Chicago, Illinois, during the Red Summer of 1919.

How are you doing during these unprecedented times?

It’s a well-intentioned, but inaccurate, rhetorical question that has become standard in 2020. Indeed, 2020 is a blockbuster year for the American history books: a global pandemic, one of the worst wildfire seasons on record, and in our social media feeds, unrelenting social unrest. But it’s all far from unprecedented - especially the protests.

Race has been an impetus for countless violent uprisings since the inception of the United States - usually with whites perpetrating the violence upon Blacks. And although the antebellum South was undoubtedly the most oppressive place and violent time for African-Americans, it’s also a widely covered, even romanticized period, teeming with blockbuster movies and best-selling literature. The consequence of this extensive treatment is that many people fail to fully understand racism in early America beyond slavery, even though race riots were common in free states. Furthermore, many white Americans tend to view well-known historical events such as the Civil War and Civil Rights Movement as punctuation marks, periods to be exact, which ended odious periods of Southern history such as slavery, racism, and Jim Crow. However, a closer look handily flips that perspective on its head. Likewise, there is no moral high ground that cosmopolitans or Yankees can claim.

The Big Apple & City of Brotherly Love

One example can be traced to 1834 when destructive riots, which targeted Blacks and abolitionists, ripped through New York City. Irish Catholics were settling in Manhattan in droves and they frequently clashed with Protestant abolitionists. Additionally, white residents resented the free Black population for becoming assertive and challenging racial norms. Tensions mounted, and white mobs ultimately burned buildings and homes, destroyed municipal property, and attacked African-Americans. They held parts of the city hostage until it all ended.

Free Blacks in Philadelphia experienced the same ugly racism as their New York City counterparts. A particularly egregious event occurred in 1838 when Pennsylvania Hall, a building erected for abolitionist and suffragette meetings, was burned to the ground by racist mobs. Not one single culprit faced any legal recourse. Originally, whites and Blacks intermingled, and a prosperous African-American community cropped up along Lombard Street. But their success did not go unnoticed and by 1842, residents of Lombard Street came under a full-scale attack by Irish immigrants, who also attacked police officers when they intervened.

Things only worsened as working-class Whites turned their animosity towards African-Americans, whom they viewed as economic competitors. Wealthy, white Philadelphians were sympathetic to the South because they shared commerce, as well as summers in beach resorts such as Cape May, New Jersey. The city that is home to the Liberty Bell and Constitution Hall can also claim some of the harshest racial violence in America’s history.

Go West!

As Americans moved west, they brought horses, carriages, and racism. Midwestern Cincinnati attracted Irish and German immigrants after the Erie Canal reached completion and ultimately became a hotbed of race riots launched by angry whites who feared economic competition from the growing population of free Blacks. Similarly, in Alton, Illinois, whites were agitated by the number of escaped slaves settling in the town due to its border with the slave-state Missouri. They feared economic reprisals from southern states and attributed the situation to a prominent abolitionist and printer Elijah Lovejoy. On November 7, 1837, a murderous mob set fire to a warehouse and shot and killed Elijah Lovejoy. The rioters evaded justice because some of the mobsters were clerks and judges.

Farther west brings us to Bleeding Kansas (1854-1861), (or Bloody, as some prefer) - a dress rehearsal for the Civil War replete with looting, arson, property destruction, battlelines, small armies, and murder. The original issue, whether Kansas should join the Union as a free or slave state, should have been settled through popular sovereignty, but that was not to be. Both sides hunkered down and belligerent pro-slavery Missourians, known as border ruffians, tampered with elections and used physical intimidation to let the Kansans know which way the wind was blowing. One particularly violent incident occurred when ruffians crossed into the town of Lawrence, a free-state concentration, and sacked, looted, and blew property to smithereens.

Interestingly, a similar vigilante scenario is surfacing today. Since May 2020, there have been at least 50 reports of armed individuals appearing at Black Lives Matter demonstrations inciting violence while claiming to be peacekeepers. One example is the Kenosha Guard in Wisconsin, a militia group that launched a ‘call to arms’ on social media encouraging ‘patriots’ to rise up and defend property from protesting ‘thugs.’ Kyle Rittenhouse answered their call. He shot three protesters, killing two.

The Misunderstanding of the Civil War

Obviously, the most violent uprising over race was the American Civil War. Insurgents in seven southern states coordinated an aggressive assault on their own countrymen by first declaring sovereignty, then attacking Fort Sumter while recruiting more rebels along the way - all to preserve chattel slavery in perpetuity. The Confederate States of America, as they called themselves, were willing to cause wanton death and destruction for white supremacy, mostly in their own backyards, which they pulled off six ways to Sunday with a million casualties and unfathomable property damage. Property sequester and destruction were key tactics for both the revolters and quashers. For example, General William T. Sherman affirmed that his March to Sea laid mostly waste to Georgia: “I estimate the damage done to the State of Georgia and its military resources at $100,000,000; at least $20,000,000 of which has inured to our advantage, and the remainder is simple waste and destruction.”

Today, Americans tend to forget all this history while admonishing protesters for property damage. They focus on the aftermath rather than the reasons. Agreeably, on its face, the aftermath is shocking. As of June 2020, it was estimated that Minneapolis amassed around 55 million dollars in damages, and Portland over 20 million. In July 2020, the Downtown Cleveland Alliance estimated over 6 million dollars in damages resulting from property ruin and lost revenue. However, evidence demonstrates that the majority of rallies have been peaceful, despite the public’s perception that protesters are laser focused on destruction. Ironically, a lot of the property destruction is because of the Civil War - protestors have toppled statues of Jefferson Davis and Stonewall Jackson in Richmond, one of Robert E. Lee in Alabama, a Confederate Defenders monument in South Carolina, and a statue of Charles Linn, just to name a few.

Isn’t it curious that there are so many monuments glorifying perpetrators who orchestrated the bloodiest riots in American history? As it turns out, revisionists successfully translated a lost cause into the Lost Cause. Around the turn of the 19th century, the Lost Cause movement lobbied to portray Confederates as freedom fighters for state’s rights rather than armed traitors in rebellion over slavery. The Civil War became viewed as a singular political event with causes exacted by both sides. But, it’s better understood as the culmination (and continuation) of a series of extremely violent and destructive uprisings because of race and slavery.

Those who cannot remember the past are doomed to repeat it

The summer of 2020 has been compared to the Long Hot Summer of 1967 when approximately 160 uprisings exploded across the United States in response to police brutality and systemic racism. Some historians have also noted parallels to 1968 - another year full of racial unrest that resulted in the permanent demise of once vibrant urban centers such as Trenton, Pittsburgh, and Baltimore. However, farther hindsight is needed for 2020 vision. For instance, the Red Summer of 1919 featured a series of violent racial clashes and like today, it happened upon the backdrop of a deadly global pandemic, the Spanish Flu. Despite the pandemic, one of the most virulent massacres against African-Americans occurred in Tulsa, Oklahoma, when angry white mobs decimated the vibrant metropolis known as Black Wall Street. Tulsa is not very different from its predecessors: Lombard Street, Alton, Cincinnati, or New York. The issues are also not much different than Minneapolis on May 26, 2020, when George Floyd was killed by police officer, Derek Chauvin.

How does this story end? It doesn’t. Today, African-Americans are disenfranchised, underrepresented, too often relegated to low-paying jobs, subjected to chronic unemployment, poverty, and overall subjugation by any standard. White Americans want to know why violent revolts are still happening and perhaps promoting raw history can help. Still, I posit there is not one single comparison to be evenly made. The whole story must find its way back into social institutions, such as schools, in the name human progress.

What do you think of the comparisons between protests in 1919 and the 1960s and those of 2020? Let us know below.