Coca-Cola is undoubtedly the most famous soft-drink beverage in the world, and we are all intimately familiar with the iconic red, white, and black color combination. But did you know that Coca-Cola at one point shed its iconic color scheme to sneak its way into the Soviet Union?

It is honestly difficult to imagine Coca-Cola being any other color; it's hardly recognizable, and yet that was precisely the point. All the effort that went into creating what we know today as “Coca-Cola Clear” was done to quench the thirst of a prominent Red Russian.

Here is the story of how the iconic beverage became a small sweet spot in the deteriorating East-West relationship of the Cold War. Chaveendra Dunuwille explains.

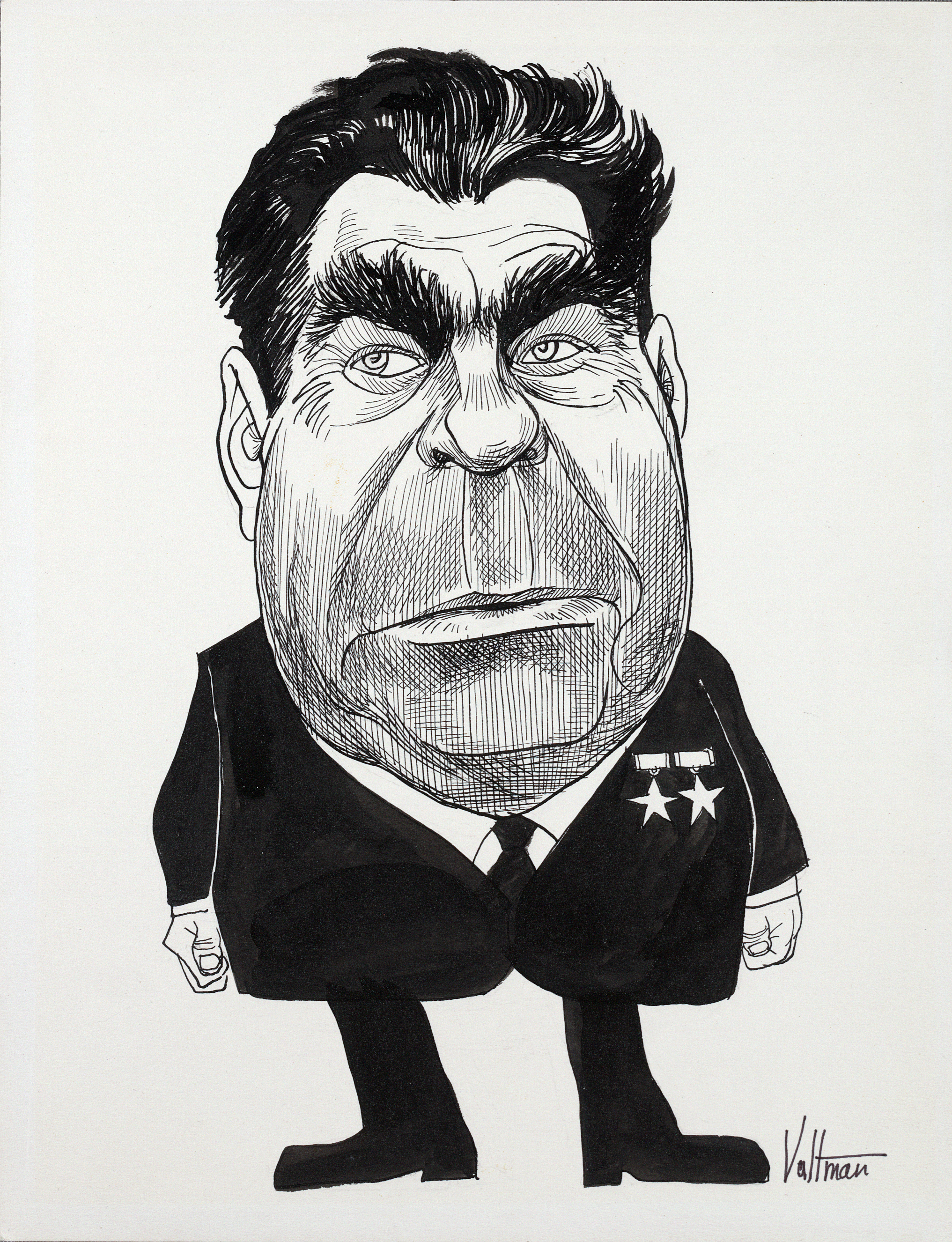

Georgy Zhukov, around 1960. Source: Mil.ru, available here.

Coca-Cola and World War II

Allied Forces

Before we get into the actual story, it is important that we comprehend how important Coca-Cola was during the war and its profound impact on both sides of the conflict.

According to Coca-Cola, the company began building its global network in the 1920s, and it significantly expanded during World War II thanks to the visionary thinking of then Coca-Cola president Robert Woodruff. The Woodruff instructed the company to ensure that every American serviceman and woman should be able to get their hands on a bottle of Coke for 5 cents, wherever they were and no matter how much it cost the company. This declaration ended up costing the company $83.2 million in today’s dollars. But Coca-Cola would agree that it was money well spent.

Coca-Cola was seen as an integral part of maintaining morale among US forces in all theaters of the conflict. During the war, Coca-Cola partnered with the United Services Organization (USO) in 1941 and played an important role in the American war effort as a much-needed morale booster for the young GIs. In 1943, General Eisenhowerordered over 3 million bottles of Coca-Cola to North Africa and requested supplies to keep refilling over 6 million bottles every month. In the Pacific theater, when Richard Bong set the American air-to-air victories record, General Henry ‘Hap’ Arnold gifted the aviator with 2 cases of Coca-Cola as a reward. In another instance, the very mention of the name Coca-Cola saved Lt Col. Robert "Rosie" Rosenthal’s life. After being shot down in one of his mission, Roshental was intercepted by advancing Soviet forces. To avoid being mistaken for a German pilot, he began to yell "Roosevelt, Churchill, Stalin, Lucky Strike, Coca Cola, bombing Berlin." This allowed the Soviets to recognize him as an American and helped him return to friendly lines. The show Masters of the Air also features Lt. Rosenthal’s interactions with the Soviets.

Whether it be Europe, the Pacific, or North Africa, the young GIs could always count on a cool, refreshing bottle of Coca-Cola to remind them of the “taste of home.” In one of their letters home, a US soldier remarked, “If anyone were to ask us what we are fighting for, we think half of us would answer, the right to buy Coca-Cola again.” - Mark Pendergrast, For God, Country and Coca-Cola (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1993)

Coca-Cola’s ad campaigns of the time heavily leaned on this rhetoric and featured almost exclusively military personnel. Today, these decisions can be credited for fostering the long-standing good relationship between Coca-Cola and the US military.

In order to keep up with the never-ending demand, the company built over 64 bottling plants across the world and sent over 200 employees to maintain the facilities. The employees that got the crates to the front lines were named the “Coca-Cola Colonels.” While they were civilians, they were issued military uniforms when operating on the front lines and given the rank of technical observer. The Coca-Cola Colonels often endured the same dangers the soldiers faced, and unfortunately, three of them were killed in action.

By the end of the war, Allied service personnel had consumed over 5 billion bottles of Coca-Cola; the company had become a quintessential part of the American identity, and the stage was set for its global expansion.

Nazi Germany

Much like in the US, Coca-Cola was incredibly popular in Germany as well. By 1929 Coca-Cola was being bottled and drunk in Germany, and by 1940, Coca-Cola was the undisputed soft-drink king in Germany, enjoyed by all levels of German society. According to some legends, Hitler himself was rumored to indulge in Coca-Cola while relaxing to watch Hollywood movies.

It would seem that the Atalanta-based company was unfazed and turned a blind eye to the events that were unfolding in the name of business. The company continued to supply its German subsidiary with syrup and other supplies during the early days of the war, and the head of the German subsidiary, Max Keith, is reported to have toured the facilities in occupied Holland and France to take over their businesses.

However, when Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, the US officially entered World War II, and American companies were ordered to immediately halt all business with the enemy. As a result, Coca-Cola HQ cut off its supply of syrup to Germany, leaving Keith stranded and Coca-Cola’s GmBH on the verge of collapse.

But ever resourceful, Keith worked with his chemists to develop a recipe that cleverly worked its way around wartime rationing by using leftovers like fruit shavings and apple fibers. While it may sound unappetizing by modern standards, the new product sold over three million cases and saved Coca-Cola GmBH. After the war, Coca-Cola refined the recipe and reintroduced this drink in April 1955, making its way to the US in 1958. This drink is none other than Fanta.

Breaching the Iron Curtain

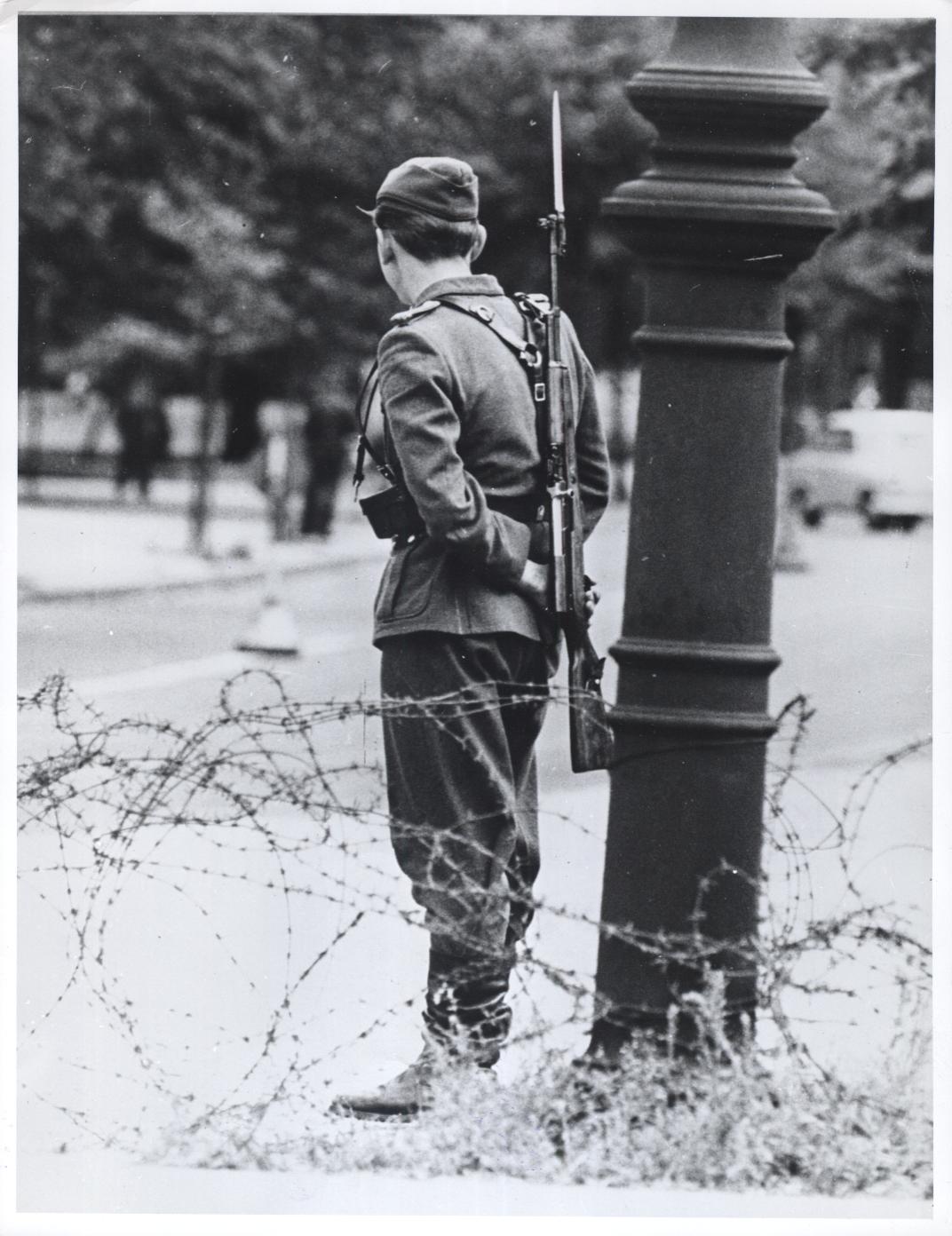

It's 1945; World War II has ended, and a new war is on the horizon, a Cold War. The old world order had collapsed, replaced by the clash of ideologies between the two new superpowers, the US and the USSR.

With its actions in World War II, Coca-Cola identified itself around the world as an icon of American culture, and this did not go on well with the Soviet Union. Despite the colors aligning, Coca-Cola’s sweetness could not breach the Iron Curtain as the Soviets viewed it as a tool of western imperialism and wanted to stave off a ‘Cocacolanization’ of the Soviet people.

However, it was during the war that a prominent Russian general, one Georgy Konstantionvich Zhukov, developed a taste for Coke that he just couldn’t seem to shake. General Zhukov is no ordinary general; he was a marshal of the Soviet Union who oversaw some of the Red Army’s fiercest battles, including the legendary Battle of Kursk. He would go on to become the 1st Commander of the Soviet occupation zone in Germany and later the Minister of Defense. Despite all the accolades and the high position in the USSR, not even he could enjoy a bottle of the famed American drink without great personal cost. Thus, he devised a clever plan that would allow him to enjoy his guilty pleasure without getting into hot water with the Communist Party.

Zhukov communicated to his US counterparts that if the iconic caramel coloring could be removed, he could pass the drink off as vodka, arguably Russia’s most famous beverage. As an added layer of security, he also mentioned that the Coke should not be filled in its usual bottles, lest some curious eyes recognize the distinct shape.

General Mark W. Clark communicated Zhukov’s request to President Truman, who then passed on the message to James Forley, the Chairman of the Coca-Cola Export Corporation. After some tinkering, the chemists at Coca-Cola managed to produce a clear variant of the iconic drink and filled it in unmarked straight bottles complete with a white lid that included a red star. Zhukov took the delivery of 50 of these Clear Coke crates, and the rest remains a mystery.

What happened to the Bottles?

We honestly don’t know what happened to those 50 crates. The fate of the Clear Coke seems to be one of those moments in history that have seeped through the cracks. Perhaps Zhukov indulged in guilty pleasure? Or was it confiscated by the Soviets? We may never know.

Did the efforts pay-off for Coca-Cola and the US?

In retrospect, you could say that the effort to make the Clear Coke and deliver it to Zhukov didn’t really pay off in the long or short term for Coca-Cola or the United States.

While Zhukov would have no doubt been personally thankful to his old American colleagues for delivering him the Coca-Cola, the interaction is relegated to history as an interesting footnote, and it did not help mend the deteriorating US-Soviet relations of the period.

At the same time, despite trade restrictions being lowered over time, Coca-Cola was effectively locked out of the Russian market due to clever marketing by their rival PepsiCo, involving the then Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev (a story for another time). Pepsi effectively maintained a monopoly in the Russian market up until 1980 when Coke came into Russia through the 1980 Moscow Olympics.

Can you get Clear Coke today?

Yes, you can. But Coca-Cola Clear is a Japan exclusive product. Its available in many major Japanese retail stores such as Lawson and Seven-Eleven. But thanks to online shopping and worldwide delivery services, you can enjoy this beverage from almost anywhere in the world.

Find that piece of interest? If so, join us for free by clicking here.

Sources

● An American GI’s best friend: Coca-Cola

● Articles - Rod Beemer | Author · Speaker · Historian

● Mark Pendergrast, For God, Country and Coca-Cola (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1993)

● The USO & Coca-Cola: A Refreshing 80+ Year Partnership