The Industrial Revolution, which saw many countries move from predominantly farming economies to industrial ones, began in England in approximately 1840. However, Spain did not experience that movement until at least roughly 1880. Janel Miller explains some of the reasons why.

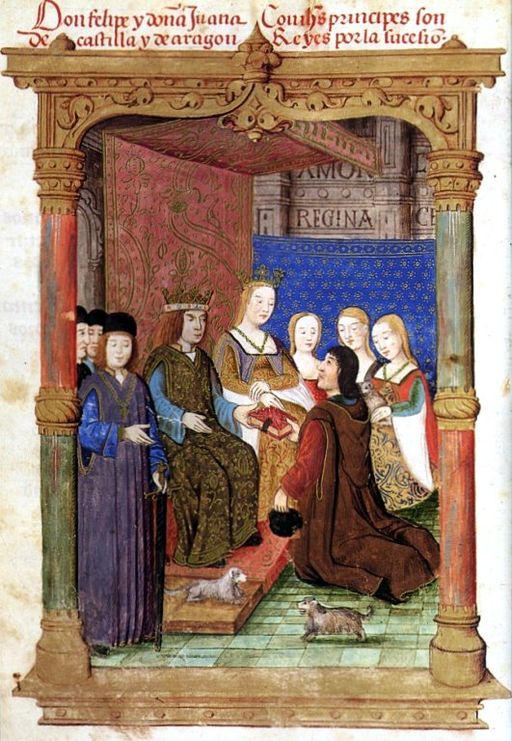

The group who built a tramline from Barcelona to Mataro in mid-19th century Spain.

Multiple Reasons for the Delay

As late as 1855, only about 20 percent of Spain’s land was considered cultivated. The rest had been “blasted by a ruinous system of exploitation.” Around the same time, criminals and beggars were rampant, formal education was not widespread and free speech was not common.

For those reasons and likely others, very few roads had been built by 1955. Compounding Spain’s ability to transport what goods it did produce and thus grow its economy was that its geography is more mountainous than all but one other European country (Switzerland). Spain also had “virtually no” rivers or canals that ships could sail on smoothly.

In the limited instances where roads did exist, it appeared that few bridges spanned waterways well into the 1860s, hindering some transportation efforts. In addition, in the 1850s and 1860s, a majority of Spain’s workforce was employed in an agricultural-based business. Spain’s coal, which was being used in large amounts by the United Kingdom (and likely at least several other countries) to support the industrial plants being built on their landscapes, was also apparently inferior to that of some of its neighbors.

As one author put it when describing Spain during some of the years discussed here, “the rest of the world had long since awakened to a life of freedom and joined in the race of modern development; Spain was still asleep, drugged with the fumes of prescribed ignorance and dictated intolerance.”

Spain’s Gross Domestic Product

Spain’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) grew only about 1.1 percent annually from 1850 until 1935. This increase was better than countries such as Italy and Britain, whose yearly GDP grew 0.7 percent and 0.8 percent, respectively, during that 85-year span.

However, Spain’s GDP was lower than that of France and Germany, each of whose annual GDP increased 1.6 percent each year from 1850 to 1935.

Efforts to Modernize Hit Roadblock

Various regimes in the 1850s and 1860s enacted several laws to try and modernize its economy. Some of these laws are discussed below.

One such law was known as the Disentailment Law in the English language. This law allowed the taking of land and the awarding of lands that once belonged to the church, state and local governments to the highest bidder.

Another such law, whose name in English translated to the General Railway Act, removed many of the “administrative” difficulties in building railways that had previously been in place.

A third law was known as the Credit Company Act in the English language. This law allowed the creation of investment banks that were similar in scope to other countries that had already begun the economic modernization process.

However well-intended these laws may have been, Spain experienced a financial crisis from 1864 to 1866 that at least partially hindered that country’s growth.

In Context

Spain’s economy during the 1850s and 1860s, when looked at how it compared to some of its European neighbors, may remind some of how Haiti’s economy compares with the relatively nearby United States. (Haiti was chosen randomly for the purposes of the comparisons that follow.)

In the United States, the GDP of the United States is more than $20 trillion, placing it first among all countries, while Haiti’s GDP is approximately $21 billion, and the poorest (or almost the poorest) country in the Americas per head of population. In addition, while roughly 10.5 percent of U.S. workers are in the agricultural, food and related businesses, about 66 percent of Haitian workers are employed in farming.

Determining the appropriate GDP to maintain a decent standard of living and the suitable number of agricultural workers a country should employ is beyond the scope of this blog.

That said, since the 1860s, Spain has gained economic ground against its neighbors, providing hope that in the future, the difference between the lower, middle and upper classes in all countries will become less apparent.

What do you think of Spain’s position in the mid 19th century?

Now read Janel’s article on the role of Brazil in World War 2 here.

References

Brittanica.com Editors. Brittanica.com. “Industrial Revolution.” https://www.britannica.com/event/Industrial-Revolution. Accessed April 2, 2023.

Tapia FJB and Martinez-Galarraga J. “Inequality and Growth in a Developing Economy: Evidence from Regional Data (Spain 1860-1930).” Social Science History. Volume 44, Number 1. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/social-science-history/article/inequality-and-growth-in-a-developing-economy-evidence-from-regional-data-spain-18601930/802599439621953BD012A8797A684DC7. Accessed March 31, 2023.

Delmar A. “The Resources, Production and Social Condition of Spain.” American Philosophical Society. Volume 14, Number 94, Pages 301-343. https://www.jstor.org/stable/981861. Accessed March 21, 2023.

Simpson J. “Economic Development of Spain, 1850-1936.” The Economic History Review. Volume 50, Issue 2, Pages 348-359. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0289.00058. Accessed March 21, 2023.

Delmar A. “The Resources, Production and Social Condition of Spain.” American Philosophical Society. Volume 14, Number 94, Pages 301-343. https://www.jstor.org/stable/981861. Accessed March 21, 2023.

Clark G and Jacks D. “Coal and the Industrial Revolution.” European Review of Economic History. Volume 11, Number 1, Pages 39-72. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41378456. Accessed April 18, 2023.

Delmar A. “The Resources, Production and Social Condition of Spain.” American Philosophical Society. Volume 14, Number 94, Pages 301-343. https://www.jstor.org/stable/981861. Accessed March 21, 2023.

Moro A, et al. “A Twin Crisis with Multiple Banks of Issue: Spain in the 1860s.” European Central Bank. No. 1561. Published July 2013. Accessed March 31, 2023.

WorldPopulationReview.com Editors. WorldPopulationReview.com. “GDP Ranked by County 2023.” https://worldpopulationreview.com/countries/by-gdp. Accessed April 17, 2023.

USDA.gov Editors. USDA.gov. “Ag and Food Sectors and the Economy.” https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/ag-and-food-statistics-charting-the-essentials/ag-and-food-sectors-and-the-economy/. Accessed April 17, 2023.

NationsEncyclopedia.com Editors. NationsEncyclopedia.com. “Haiti-Agriculture.” https://www.nationsencyclopedia.com/Americas/Haiti-AGRICULTURE.html. Accessed April 17, 2023.

Simpson J. “Economic Development of Spain, 1850-1936.” The Economic History Review. Volume 50, Issue 2, Pages 348-359. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0289.00058. Accessed March 21, 2023.