William McKinley was the 25th president of the USA - from 1897-1901. While before becoming president his political career was focused on Ohio, there was a status of McKinley in Arcata, California until it was toppled in February 2019. Here, Victor Gamma returns and looks at the case for and against the removal of the statue. In part 3, we look in depth at McKinley’s relationship with African Americans.

If you missed it, in part 1 here Victor provides the background to the statue removal and in part 2 here he looks at McKinley’s relationship with Native Americans.

Booker T. Washington, an educator, orator, and advisor to US presidents. Washington met with William McKinley.

The protestors in Arcata, California accused the 25th president of supporting “racism and murder.” How does this charge stand up? From his youth McKinley shared the strong anti-slavery and pro-union views of his family. Not long after the fall of Fort Sumter, the young McKinley answered his country’s call and volunteered for service. He served bravely throughout the conflict, rising to the rank of major. He, in fact, liked to be referred to as “The Major” for the rest of his life. As such he played his part, along with millions of others, in re-uniting the nation and freeing the slaves. During his political life he remained steadfastly dedicated to the party of Lincoln and full civil rights for the ex-slaves. His first political speech took place in 1867. His theme? Give African Americans the vote. He spent a good amount of that year continuing to work for this cause.

His campaign for African American suffrage and equal rights for African Americans did not end in 1867. After election to congress in 1876 he continued to advocate for disenfranchised African Americans. On April 28, 1880 at the Republican State Convention in Columbus, Ohio he attacked the Democratic suppression of African American voting rights. He described the Democratic effort to establish one-party rule in the South and the almost complete suppression of opposition political activity. Using the example of a largely African American district he denounced the fact that the population had “been disenfranchised by the use of the shotgun and the bludgeon.” He then challenged his audience with a burning question:

“Are free thought and free political action to be crushed out in one section of the country? I answer No, no! But that the whole power of the Federal Government must be exhausted in securing every citizen, black or white, rich or poor, everywhere within the limits of the Union, every right, civil and political, guaranteed by the Constitution and the laws.”

1880s and African American votes

McKinley continued hammering at this theme throughout the 1880s, referring to “Southern outrages” and reminding his fellow congressmen that the small number of African American representatives was proof that African Americans were being denied the vote in the South. He continued to uphold the Old Guard Republican ideal long after many had given up on Reconstruction. One such speech appealed to the desperate need to enforce the Reconstruction Amendments:

“...the consciences of the American people will not be permitted to slumber until the great constitutional right, the equality of the suffrage, equality of opportunity, freedom of political action and political thought, shall not be the mere cold formalities of constitutional enactment as now, but a living birthright which the poorest and humblest, white or black, native born or naturalized citizen, may confidently enjoy, and which the richest and most powerful dare not deny.”

McKinley and the 1896 election

Throughout his career McKinley sought African American support. While in Congress he supported Reconstruction and opposed the white-supremacist policies of the Democrats. He received African American delegations both in Georgia while staying with friend and supporter Mark Hanna, and at his home in Ohio during the run for the White House. During this stay in Georgia, which was essentially a campaign trip, he became the first presidential hopeful-nominee in American history to address an African American audience. On this occasion he spoke at an African American church. When it came time to officially run for the nation’s highest office, McKinley conducted his run entirely from his front porch. During the presidential election campaign of 1896, hundreds of delegations made their way to Canton, Ohio to show support or hear from the candidate. Included among these visitors were several African American delegations that made the journey to the candidate’s front porch to show their support. African Americans as a whole supported McKinley because, during this time of the rise Jim Crow, they knew he did not support increasing discrimination. Bishop B. W. Arnett, of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, stressed to McKinley that: “We come to assure you that we will never cease our efforts on your behalf until we have achieved such a victory in November as was won by our fathers in their early struggles for liberty… you represent the cardinal principles of the Republican Party which have so benefited our race—the principles for which you and your comrades struggled from 1861 to 1865.” Another African American delegation, this one from McKinley’s own Stark County, had first-hand knowledge of the candidate’s character and policies. On July 3, 1896 this local organization came to see their candidate. William Bell of Massillon, Ohio delivered a brief message of support as follows:

“You have always treated us, just as you do everybody else . . . with great consideration and kindness, and on every occasion have been our friend, champion and protector. We come to congratulate you and assure you of our earnest support until you are triumphantly elected next November.”

The front porch candidate’s own remarks to African American groups included the following statements: “It is a matchless civilization in which we live; a civilization that recognizes the common and universal brotherhood of man.”

McKinley as president

As governor and president McKinley condemned lynching - a quarter of a century before Congress finally found within itself the conviction to pass anti-lynching legislation. Let’s look at McKinley’s statement in context:

“These guarantees (basic freedoms such as speech) must be sacredly preserved and wisely strengthened. The constituted authorities must be cheerfully and vigorously upheld. Lynchings must not be tolerated in a great and civilized country like the United States; courts, not mobs, must execute the penalties of the law. The preservation of public order, the right of discussion, the integrity of courts, and the orderly administration of justice must continue forever the rock of safety upon which our Government securely rests.”

Despite the pressures of changing times, McKinley never wavered from adherence to the tenets of the party of Lincoln. He maintained and extended the traditional Republican inclusion of African Americans in government and expressed support for their cause. He spoke against having the nominating convention to be held in St. Louis for fear that African American delegates would not be able to get a hotel room. He once refused to stay at a hotel that would not serve African Americans. He included two African Americans on his inauguration committee. He appointed several African Americans to government positions. He was the first U.S. president to visit the Tuskegee Institute (established in 1881). He went 140 miles out of his way to do so. This act was of signal importance in bringing attention and support to this educational institution which was doing so much to help African Americans improve their conditions of life. When the Spanish-American War broke out, McKinley was diligent to make sure that African American soldiers served, even reversing orders attempting to prevent the recruitment of African American soldiers. Military service was an important part of the on-going process of African Americans gaining respect from white society as they performed valuable service and demonstrated their valor.

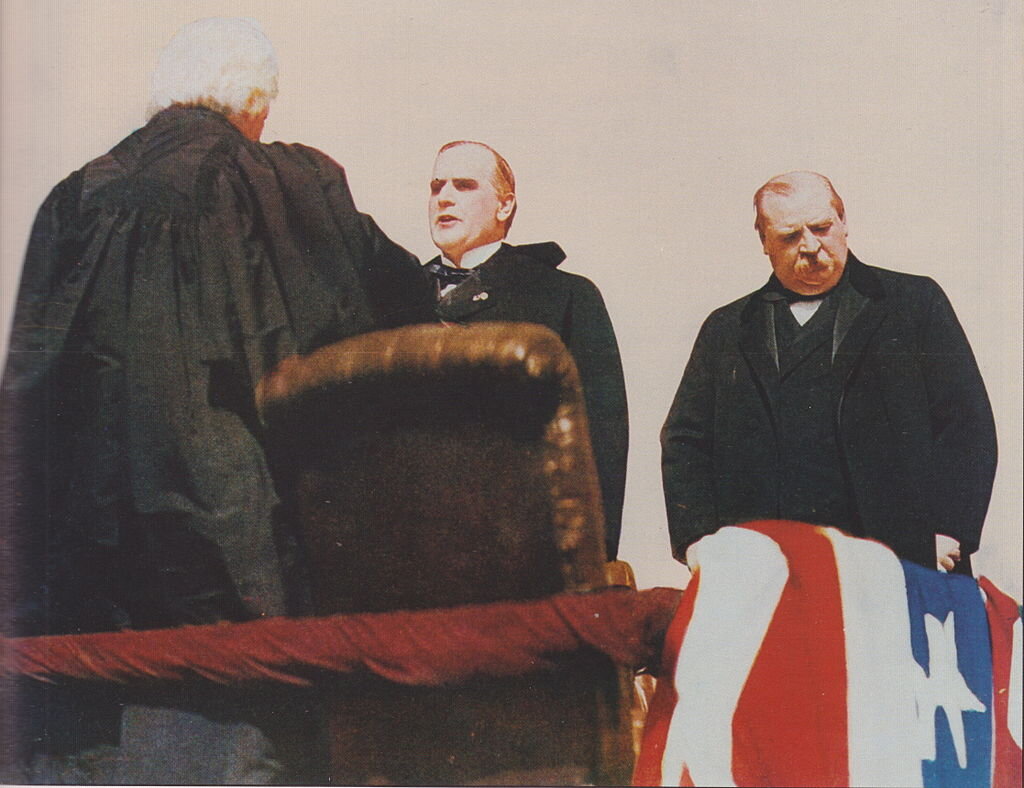

The Major also met with African American leaders such as Ida Wells and Booker T. Washington at the White House more than once. This event took place years before Theodore Roosevelt's famous White House meeting with Washington. The great educator recorded his impressions of McKinley and their meeting on his second visit to see McKinley. At this time a number of race riots had recently taken place in the south. Washington noted that the president seemed “greatly burdened by reason of these disturbances.” Despite a long line of people waiting to see the president, McKinley detained Washington for some time to discuss the current condition of African Americans. He remarked repeatedly to Washington that he was “determined to show his interest and faith in the race, not merely in words, but by acts." The fruit of this meeting was the first visit to Tuskegee by a sitting president of the United States.

Conclusion

Could he have done more? Certainly. Beyond the measures discussed here he was not notably pro-active in improving the situation regarding civil rights. What he did was to maintain the Republican tradition followed by his predecessors and sympathize with the plight of African Americans. However, in the words of a McKinley historian, “given the political climate in the South, there was little McKinley could have done to improve race relations, and he did better than later presidents. Theodore Roosevelt, who doubted racial equality and Wilson who supported segregation.” He did not share the radical Reconstructionist vengeful attitude toward the defeated South but rather all his life advocated reconciliation between the two sections. It must be understood that at the time the memories of the Civil War were still fresh and the need to strengthen the bonds of union still dominated the American consciousness. One of McKinley's key objectives was to continue healing the wounds of the old separation and to do everything he could to build unity between the sections. Pushing too hard on civil rights would have destroyed that effort. He may not have been a strong civil-rights advocate, but he did accomplish several ‘firsts’. In the last analysis, his actions and policies were certainly a far cry from “racism and murder.”

Now in part 4 here, the final part in the series, you can read about McKinley’s character.