In this article, Chris Marsh continues his tale of the Wars of the Three Kingdoms in Scotland, and concludes with the legendary Battle of Inverlochy.

At the end of the last post, we left Montrose and Alasdair and their small army marching away from Inverary in mid-January 1645. A force of some 3,000 men, they were laden with booty and the principal township of the lands of Clan Campbell sat a smoking ruin behind them.

This small Royalist army, fighting to secure Scotland for King Charles I, had won two of the six victories that they were ultimately to secure, but the circumstances in which they now found themselves could scarcely be less favorable. They were deep in the hostile territory of Argyll in the depths of winter. The Marquis of Argyll, Chief of Clan Campbell and de facto head of Scotland’s covenanting government was assembling strong forces to attack them and avenge this assault on his home territory and, equally importantly, his personal political status.

Additionally, but probably unbeknownst to Montrose, General William Baillie had been newly appointed as the commander in chief of the government forces. An old soldier of Gustavus Adolphus and veteran of Marston Moor, Baillie was his own man and did not hesitate in refusing to take instructions from Argyll when they met to discuss the pursuit of the Royalist army. Although he did transfer to the Earl’s command some 1,100 of his regular troops, Baillie now sat in Perth with a sizeable force thus constituting a significant but unknown threat to the eastern flank of Montrose’s route north.

The Old Inverlochy Castle, with Ben Nevis in the background. Source: DJ Macpherson, from geograph.org.uk. 2008.

The whole campaign, this famous Year of Victories, is often presented as a random perambulation of epic marches over snow-bound mountain passes punctuated by spectacular military victories with perhaps insufficient effort taken to understand the aims and purpose of the King’s Captain-General.

And it is at this point that we might more closely examine the situation in which he found himself and the options that were open to him, all seen within the context of what it was he was trying to achieve.

In England, the King’s army under Prince Rupert had suffered a heavy defeat at Marston Moor the previous summer but was still in the field and final victory remained possible. Ultimately the field actions which would determine the winner in the struggle between the King and his parliaments would be fought in the southern Kingdom. Montrose, therefore, had to first win Scotland for his King then take his army south to join with Rupert and defeat the army of the English Parliament. Only then could Charles be restored to the unified throne.

IN HOSTILE TERRITORY

All of this was still a long way off. The immediate task facing Montrose was to defeat conclusively the various armies of the Scottish covenanting parliament. As he marched his army north from Argyll negotiating the comb-fretted difficulties of the landscape of the west highland coast where the land was punctuated by deep sea lochs and boats were a scarcity, he would have been considering how best to achieve this goal.

Within a week they had made it to Inverlochy in the friendly territory of Lochaber where, as they rested, they were joined by further reinforcements as various clan chiefs, pushed off the fence of vacillation by the outcome of the remarkable attack on Inveraray now, rallied to the King’s standard.

However, much of Scotland was still hostile territory for the King’s army. In the far north at Inverness, the Earl of Seaforth, Clan Chief of the MacKenzies, who like many powerful men in Scotland had for long avoided full commitment to either cause had recently declared against the King. It was likely that he would soon be heading south down the Great Glen at the head of another sizeable force, bent on the destruction of Montrose’s command. By now Montrose would be aware of Baillie’s army positioned to the east in Perth and confirmation was also received that the Earl of Argyll approached from the south with the remainder of his Clan Campbell’s soldiery as well as the 1,100 hundred men supplied by Baillie.

Positioned thus between three hostile forces, each of which matched or exceeded his own in size, he probably determined that the best course of action was to seek out Clan Gordon in the north east. The Gordons were second only in size and martial strength to the Campbells. And alone among the highland clans they had a measurable element of mounted men at their disposal. The Marquis of Huntly, Chief of Clan Gordon, had hitherto declined to declare support for his beleaguered monarch. Partly through resentment that Montrose had been given the royal commission in the first place, a rank which diminished his own of Lieutenancy of the North, and partly also due to previous disagreements between the two men during the Bishops Wars half a dozen years previously.

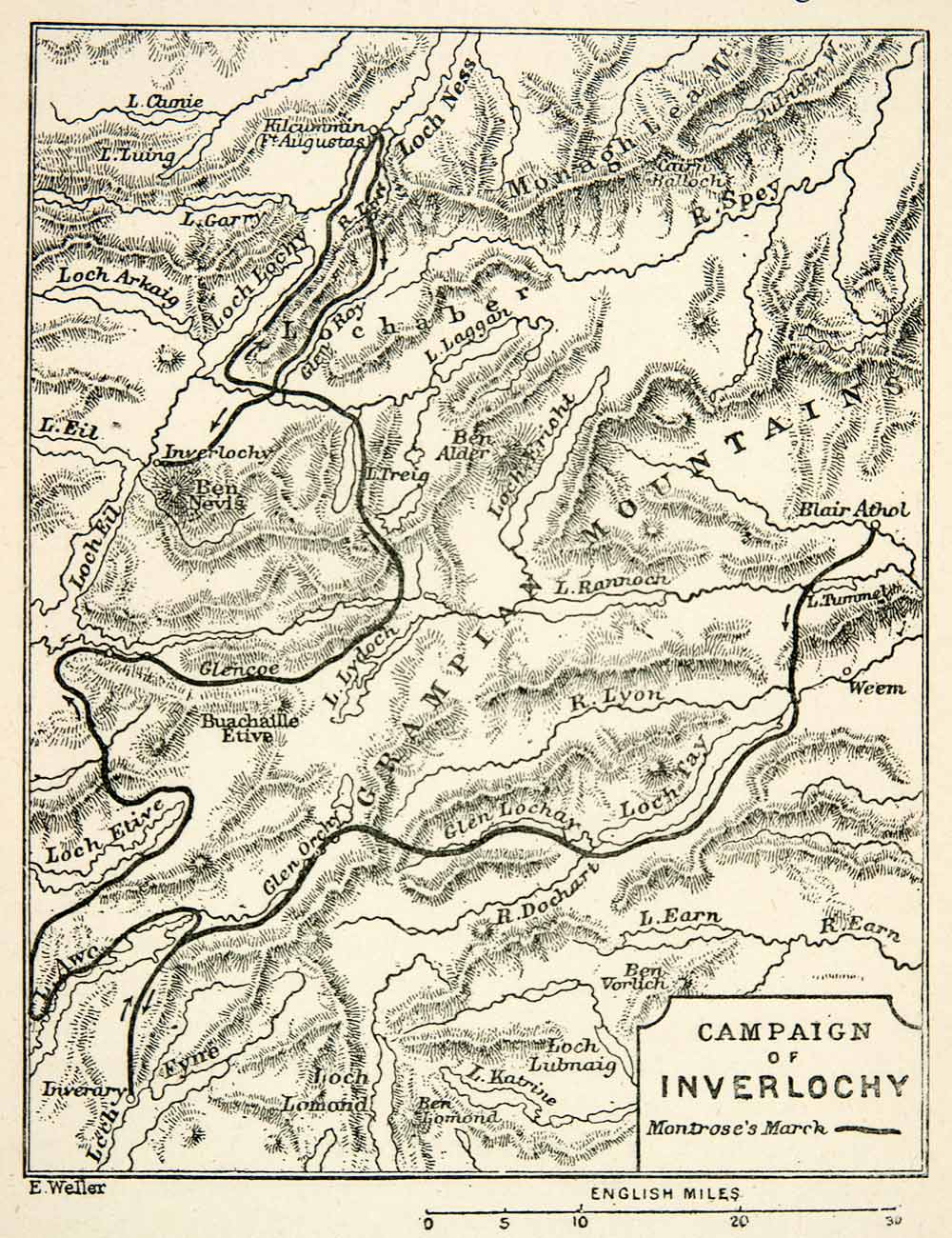

Nonetheless, in Montrose’s eyes, despite his victories at the Battles of Tippermuir and Justice Mills and the recent outstanding success in sacking Inverary, the struggle in Scotland now required the input of the Gordons if it were to be ultimately successful. And it was this challenge of persuading Huntly to throw in his lot with his King which would have pre-occupied Montrose’s mind as he led his army up the Great Glen where they overnighted at Kilcumin (now Fort Augustus) on the evening of January 31.

MONTROSE CHANGES THE PLAN

Events, however, were about to overtake him and his plans for sweet-talking the Marquis of Huntly would have to be shelved forthwith. Firstly a messenger arrived at their camp confirming that the Earl of Seaforth had assembled some five thousand men, Mackenzies and Frasers mostly but also two regiments of regular soldiery. Presently, some thirty miles away, they were about to march directly down the Great Glen to engage him. As he weighed up the implications of this news another messenger arrived. He had been sent north from Lochaber by the Chief of the Camerons of Lochiel and advised that the Earl of Argyll had arrived at Inverlochy, thirty odd miles to the south, with over three thousand men and was on the point of heading up the Great Glen to find and engage Montrose.

So what now for the King’s Captain-General? A numerically superior force approached from the north, with another heading up from the south similar in size to his own and hell-bent on revenge. Baillie’s army blocked the route east, and to the west there was only the winter-gripped barrenness of the highland seaboard.

Negotiations with Huntly and the work of increasing the size of the King’s army would now have to wait as the fate of the royalist army, with it, the King’s cause in Scotland, and perhaps throughout the three kingdoms, was now threatened with disastrous defeat.

Stood around the campfire on that winter’s evening, Montrose, Alasdair MacColla and the principal clan chiefs now discussed their options. Seaforth’s force was perhaps twice their size, but the caliber of much of that they knew to be questionable. But Argyll’s assembly of Clan Campbell’s finest fighting stock, notwithstanding the losses suffered in the attack on Inverary, was a different matter altogether and included the 1,100 regulars handed over by Baillie. And even if Montrose were to engage and defeat Seaforth, Argyll’s men would still need to be faced in turn. Furthermore it was clear that as this force had made their way north they had taken time to burn and pillage through the territory of any believed to be in sympathy with Montrose. Men who stood with him now were moved to protect their own lands.

Thus the decision as to their next move made itself. Once victorious over Argyll they could then march to Gordon country, with a greater likelihood of success in persuading them to join forces.

INTO HISTORY

However, to simply turn about and head back down the glen to attack Argyll was to invite defeat. It would require a different approach if their unlikely record of success was to be maintained. And so in the dark of the following morning, Friday January 31, Montrose and his army of three thousand men embarked on that legendary flank march which has been deemed one of the great exploits of arms in the history of the British Isles. With the Great Glen carving a gash from south east to north west, they disappeared south east up the rocky course of the little River Tarff and disappeared into the mountains.

Over the next thirty-six hours they covered over thirty miles in weather as unkind as the Scottish winter can deliver, as Argyll and Seaforth’s scouts combed the Great Glen fruitlessly. Late on the Saturday evening they crossed over the northern buttress of Ben Nevis’ long slope and looked down upon the dark mass of Inverlochy Castle with the many camp fires of Clan Campbell dotted around it. The surprise was complete. Montrose, who had been confirmed at Loch Ness not two days before, now stood at the head of his army ready to attack them.

Argyll himself, recently injured in a horse fall and with little stomach for pitched battle, conferred full authority on his kinsman Duncan Auchenbreck, who he had, to be truthful, recalled from Ireland specifically to lead this army. And the Chief of Clan Campbell was rowed out to his waiting galley which sat at anchor safely out on Lich Linnhie.

Both armies lined up in battle order and waited out the remainder of the freezing night. As soon as there was deemed to be enough light to fight by, Alasdair, at Montrose’s direction led the two flanks of Irishmen forward. When they were close to the enemy they fired their muskets, then followed up with sword and dirk. In just a few minutes the enemy flanks were in disarray and the center quickly followed suit with many of the regular troops fleeing the field. At this point Montrose took the royalist center forward and completed the rout.

Inverlochy was to be one of the bloodiest battles fought on Scottish soil, and as is so often the case in such circumstances, the majority of the slaughter was carried out on a terrified and defeated rabble as they fled the field. About 1,800 men of Argyll’s force met their end, some as far away as ten miles from the battlefield.

This success following so close on from the triumph of the raid on Inveraray would have been more than Montrose could have hoped for just two months previously. In the immediate aftermath of the fight he wrote a comprehensive dispatch to his King detailing the recent successes and anticipating, not without some cause, ultimate victory.

This article was written by Chris Marsh, who blogs at www.bonniedundee1689.wordpress.com.

Enjoy the article? If so, like it, tweet about it, or share it by clicking one of the buttons below!