War is full of unlikely stories, isn't it? But what happened at Castle Itter in May 1945 almost defies belief. Imagine this: American soldiers, disillusioned German troops, and French political prisoners standing shoulder to shoulder to fend off a Waffen-SS attack. It sounds like something out of a dramatic wartime novel, or a late-night history channel special, but it's not. This really happened, complete with all its strange twists and turns.

Richard Clements explains.

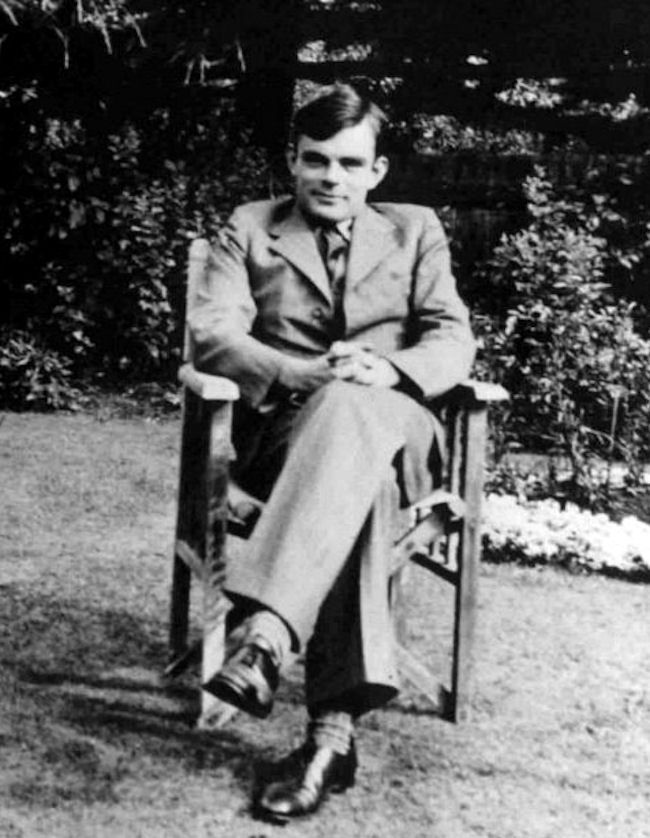

Major Josef Gangl.

Castle Itter: A Fortress of Contrasts

Nestled above the Austrian village of Itter, Castle Itter has seen its share of transformations over the centuries. Originally a medieval fortress, it evolved into a 19th-century Alpine retreat, the kind of place you'd imagine travelers visiting for fresh air and sweeping mountain views. Picture it: quiet mornings with coffee on the terrace, surrounded by the majesty of the Tyrolean Alps. But history has a way of disrupting even the most tranquil settings.

In 1938, when Nazi Germany annexed Austria, the castle's fate changed dramatically. The Nazis took over and, by 1943, had turned this once-idyllic spot into a high-security prison for France's most influential captives. I've always found it jarring to imagine, a place that once welcomed guests with charm now holding figures like former French premiers Édouard Daladier and Paul Reynaud under lock and key. The contrast between its picturesque exterior and the grim reality inside is hard to shake.

Desperation and Calls for Help

By early May 1945, the Third Reich was in free fall. Hitler was dead, Allied forces were advancing on all fronts, and German command structures were collapsing. Castle Itter's SS guards, sensing the end, fled their posts. For the prisoners, their temporary freedom was bittersweet. They were unarmed, surrounded by hostile forests teeming with Waffen-SS troops, and unsure of their fate.

Their first hope came in the form of Zvonimir Čučković, a Yugoslav handyman. Risking everything, Čučković slipped out of the castle with a plea for help. He eventually reached American troops near Innsbruck. Meanwhile, Andreas Krobot, the castle's Czech cook, pedaled to the nearby town of Wörgl, where he found Major Josef Gangl, a Wehrmacht officer who had turned against the Nazis. Gangl was already working with Austrian resistance fighters to protect local civilians from SS reprisals.

Gangl's decision to side with the Allies wasn't simple. A decorated veteran of the Eastern Front, he had seen more than his share of the horrors inflicted by Nazi ideology. By May 1945, his disillusionment was complete. Protecting the prisoners at Castle Itter wasn't just a strategic choice; it was a deeply personal stand against a regime he no longer believed in.

An Unlikely Alliance

Gangl sought out Captain Jack Lee, a tank commander in the U.S. 12th Armored Division. When I picture their first meeting, I imagine a tense moment. Gangl, a former enemy, approaching with a white flag, hoping the Americans wouldn't shoot first and ask questions later. To Lee's credit, he listened. Gangl explained the situation, and the two men devised a rescue mission. It wasn't a large force – just a handful of American soldiers, some of Gangl's defecting troops, and Lee's Sherman tank, nicknamed Besotten Jenny.

By the time they reached the castle, night was falling, and tensions were high. Inside the castle, the prisoners had armed themselves with whatever they could find. Jean Borotra, the French tennis star, had taken charge of organizing them, though most were untrained in combat. Lee and Gangl knew they were outnumbered and outgunned, but retreat wasn't an option.

The Battle Begins

The Waffen-SS launched their attack at dawn on May 5, 1945. Machine gun fire rained down on the castle, and the SS deployed a formidable 88mm flak cannon. Besotten Jenny provided critical support until it was destroyed by enemy fire. The defenders, American GIs, Wehrmacht defectors, and French prisoners, fought side by side. Gangl, ever the protector, was killed by a sniper while trying to shield one of the French leaders from harm.

Jean Borotra was an unexpected figure in this story. A celebrated tennis champion and former French official, he seemed far removed from the violence of war. Yet, by the time he stood with a rifle in Castle Itter, the choice was clear, fight or face certain death. His courage, like that of many others in this strange battle, was a testament to the resilience of those thrust into unimaginable circumstances.

As the situation grew desperate, Borotra volunteered for a daring mission. Scaling the castle wall, he slipped past enemy lines to find reinforcements. It's hard not to marvel at his courage. Imagine sprinting through a war zone, unarmed, knowing that every step could be your last. But Borotra succeeded. He reached a nearby U.S. unit, and by mid-afternoon, reinforcements arrived. Tanks rolled up the hill, scattering the SS and securing the castle.

Relief and Redemption

By the time the battle ended, the defenders had achieved the impossible. Around 100 SS soldiers were captured, and the castle was safe. But the victory came at a cost. Major Gangl's death was a reminder of the sacrifices made by those who stood against tyranny, even at great personal risk.

Gangl was posthumously honored as a hero of the Austrian resistance, with a street in Wörgl named after him. Captain Lee was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for his leadership. The French prisoners, including Borotra, returned to France as symbols of resilience and survival.

A Moment of Shared Purpose

The Battle of Castle Itter is more than a bizarre historical event – it's a stark reminder of how humanity can emerge in even the darkest moments of war. Think about it: American soldiers and disillusioned Germans, once fierce adversaries, joining forces to defend French prisoners. For a few hours, all the labels – enemy, ally, prisoner, faded, leaving behind something simpler and more profound: the will to survive together.

When I reflect on this story, it's the humanity that stands out. War often draws hard lines between people, but this battle reminds us that those lines aren't as immovable as they seem. Sometimes, shared danger is enough to bring people together, even when everything else says they should be divided.

The Castle Today

Castle Itter still stands, quiet and unassuming, on its hill above the village. Its weathered stones, scarred from the events of May 1945, seem almost reluctant to reveal the extraordinary story they witnessed. To me, that makes its story even more compelling. It's not just a relic of history; it's a reminder of what can happen when courage and circumstance push people to rise above the divisions of war.

This is a tale worth telling, not just for its strangeness, but for the glimpse it offers into the complexities of human nature. The walls of Castle Itter hold more than memories; they hold a legacy of unity in the face of chaos.

The site has been offering a wide variety of high-quality, free history content since 2012. If you’d like to say ‘thank you’ and help us with site running costs, please consider donating here.

References

· Bell, Bethany. "The Austrian Castle Where Nazis Lost to German-US Force." BBC News, 7 May 2015.

· Harding, Stephen. The Last Battle. Da Capo Press, 2013.

· Rampe, Will. "Why the Battle of Castle Itter Is the Strangest Battle in History." The Spectator, 28 April 2022.

· Wands, Christopher. "Strange History: The Battle of Castle Itter." The Historians Magazine, 2022.

· Various authors, "Battle of Castle Itter," Wikipedia, accessed 2023.