Crime in the nineteenth century was varied and often driven by poverty. In this intriguing article, Janet Ford looks at a newspaper from the city of Birmingham, England in 1872 in order to deduce the types of crime committed and some possible reasons why it was these crimes that were committed.

Crime has always been an interesting and in many cases shocking subject, as there are so many different types of crime and such a variety of criminals. It can also show what society, people and a place were and are like. To get an understanding of crime during a certain time and in a certain place, I am going to look at a week in March 1872 in the city of Birmingham in the UK using the newspaper, the Birmingham Daily Post. I only looked at reports that happened in the city of Birmingham itself, as the newspaper also reported on major crimes that occurred in the wider region and across the country.

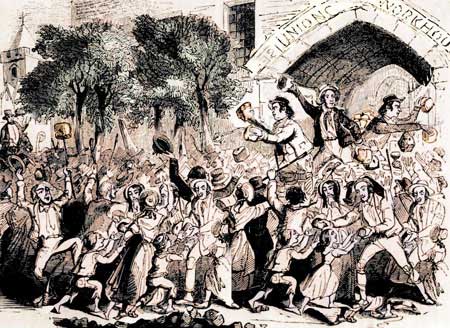

A riot/attack outside a poorhouse - in this article we look at more low-level crime.

During the week I chose, there were 40 crimes reported in Birmingham. The crimes were stealing, assaults on strangers and wives, vandalism, drunk and disorderly behavior, refusing to work, receiving stolen goods, selling beer without a license, and having a pub open after hours. These crimes show that there was a variety of crime committed in the week from March 18, 1872.

Theft – The most common crime

The majority of the crimes were theft related, with 28 such crimes being reported. This means stealing was very much part of daily life for many. Both men and women, young and old, committed the crime, which also means stealing was not limited to one group of people. The reason why so many of the crimes were theft related was down to opportunity, as cities had a great deal of places to steal from, such as shops, employers’ houses and even other people. But there was a great deal of poverty within the city, and so people stole in order to survive. These reasons illustrate that life in nineteenth century Birmingham, like many other cities, was a struggle for many. There were many items stolen, from food to boots, animals to money. There was also a great deal of metal and jewelry stolen, which was due to them being major industries within Birmingham. In fact they were such big industries that areas of the city were named after them, including Jewellery and Gun Quarter. This means the city itself affected what was and could be stolen. An example of one of the many theft reports is shown below.

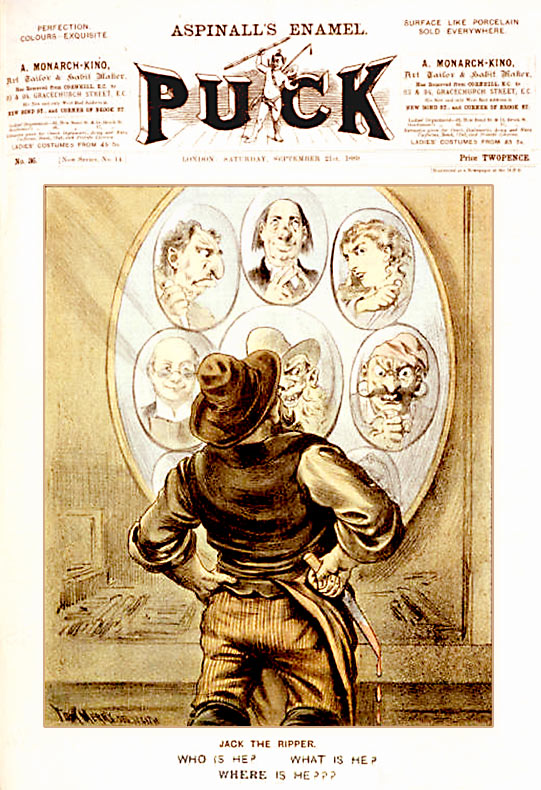

Assaults, vandalism and theft were not uncommon either. Such violence was not aimed towards just one group of people, as both men and women, strangers and people the criminals knew, were assaulted. Two husbands actually attacked their own wives - domestic violence was a sadly common part of Victorian society. Here is one example of this crime.

However, both men and women could use violence and force, as there were female pick pockets and thieves, as shown with this report.

The public house

The crimes also show that the control of pubs were taken seriously, as a person had to have a license to sell beer. This probably did not stop some people selling beer, but they were fined or spent time in prison if they were caught. And the hour that pubs were allowed to open was controlled. The reports for these crimes can be seen here.

This control was due to the government’s view of alcohol and concerns over public health. In terms of public health, they had to control the quality of the beer and who was selling it, as poor quality beer could cause people harm. The government controlled pub opening hours, as it generally had a negative view of drinking. After all, it caused negative effects on the public, such as drunk and disorderly behavior and theft. Two out of the three such pub licensing related criminals were actually women, which means pubs were not limited to just men. While it was difficult for women to have power and control within many spheres of the economy, pubs actually allowed women to have some control.

Many of the crimes occurred in employers’ houses, with servants stealing money, kettles and such. This was down to it being easy to do, but it also shows that servants were not afraid to steal from their own employers, which could have been down to wanting extra money or stealing what they thought they could get away with. An example of a servant stealing is shown here.

28 of the criminals were men and 12 were women. This illustrates that even though women committed crimes, they were in the minority when it came to being criminals. The vast majority of the crimes women committed in that week were theft related. There was also one being drunk and disorderly, one selling beer without a license, and another having their pub open after hours.

An interesting aspect of the criminals were their ages - they ranged from 14 to 55. However, there were more in certain age groups; 10 were in their teens, 6 in their 20s, 11 in their 30s and 3 in their 40s and 50s. This suggests that crime was not as common within the older population, possibly down to the role of drink, poverty and work.

In conclusion

Overall, the crimes within that week of March show that theft was common, and possibly that cities in the Victorian era were violent, while some people were opportunists. But it also demonstrates that various other crimes, such as the quality of beer, if a person worked or pub opening hours, were taken very seriously.

Much like today, the crimes people were arrested for reflected the authorities’ primary preoccupations.

Did you find this article interesting? If so, tell the world! Tweet about it, like it, or share it by clicking on one of the buttons below.

References

Birmingham Daily Post, March 1872

Report One: Tuesday 19th March 1872

Report Two: Tuesday 19th March 1872

Report Three: Wednesday 20th March 1872

Report Four: Thursday 21st March 1872

Report Five: Saturday 23rd March 1872