Charles Darwin’s remarkable travels aboard HMS Beagle opened his eyes to the concept of natural selection and paved the way towards a scientific and human revolution. In this article, Davide Previti explains the importance of the voyage and what happened when Darwin returned to Britain.

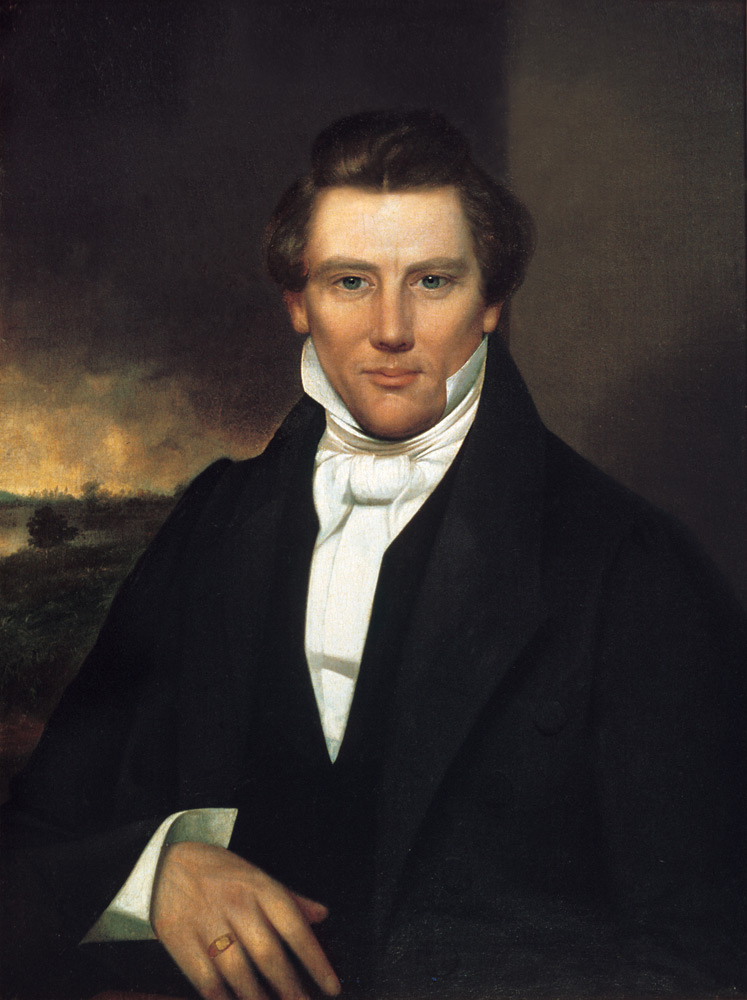

A photograph of Charles Darwin from 1881. By Herbert Rose Barraud.

In December 1831 Charles Darwin set off on the historic journey that would lead him to write The Origin of the Species. This was a book that would not only begin a scientific revolution but would also be responsible for changing our perception of humanity and of our position in the world.

As he experienced earthquakes and volcanoes he came to understand how the earth changes, he found the fossils of extinct mammals that would make him question the fixity of species, and he realized that both animals and humans must compete to survive.

A Chaos Of Delight

Darwin was offered the chance to join Robert Fitzroy, the Captain of the rebuilt brig HMS Beagle on a voyage to Tierra del Fuego at the tip of South America. Fitzroy feared the loneliness of command and invited Darwin to accompany him as the ship’s naturalist. Darwin brought weapons and books for the journey and the Beagle set sail from Plymouth in southern England with a crew of 73 on December 27, 1831.

The voyage was not an easy one as Darwin suffered from terrible seasickness; however the physical hardships he had to endure were offset by the incredible opportunities he was presented with to explore the world. As the ship’s naturalist, Darwin was able to leave the confines of the Beagle to pursue his own interests and as a result, over the course of the five-year voyage, he only spent 18 months aboard HMS Beagle.

In Brazil, Darwin witnessed slavery first hand and pondered how sustainable the system could be, noting in his diary:

“If the free blacks increase in numbers (as they must) and become discontented at not being equal to white men, the epoch of the general liberation would not be far distant.”[1]

It was also in Brazil that Darwin found the Rainforests that would leave his mind in ‘a chaos of delight.’ He spent months in Rio de Janeiro studying ‘gaily coloured’ flatworms and spiders. It was here that Darwin would find evidence against the beneficent design of nature when he witnessed parasitic wasps that would lay eggs inside live caterpillars, which would then be eaten alive by the grubs when they hatched.[2] Darwin also discovered fossils and the bones of huge, long extinct mammals, which raised questions about what could have caused these animals to die out.

On the final leg of the voyage Darwin completed his diary and completed 1,750 pages of notes. He packed up all his samples, the fossils, skins, bones and carcasses he had collected. This was the raw material he would use to formulate his theory of evolution.

Heresy and Corruption

The fossils Darwin had collected fuelled his speculations. In 1837 he became a convinced transmutationist (evolutionist) after his Beagle collections had been examined by expert British naturalists.[3] He had brought back the fossils of huge extinct armadillos, anteaters, and sloths that he hypothesized had been replaced by their own kind according to some unknown “law of succession of types.” These theories were considered, by Cambridge clerics as:

“bestial, if not blasphemous, heresy that would corrupt mankind and destroy the spiritual safeguards of the social order.”[4]

As a Unitarian, Darwin based his beliefs on reason and experience. He used such beliefs to frame his image of mankind’s place in nature, stating in his first evolutionary notebook:

“Animals whom we have made our slaves we do not like to consider our equals. Do not slave holders wish to make the black man other kind? Animals with affections, imitation, fear of death, pain, sorrow for the dead, respect.”

Darwin continued to question religion, especially Christianity. Identifying himself as agnostic, he would eventually stop believing in Christianity altogether and instead adopted natural selection as his deity.[5] For years Darwin filled his notebooks with ruminations and ideas. He considered extinction and noted his theory that life represented a branching tree rather than a ladder that humans sat at the top of.

At this time Darwin was not the only scientist that had theories of evolution. The difference between his notion and those of his peers was that Darwin put forward the unique idea of natural selection, a theory that explains how and why evolution happens.

It is said that Darwin first began to formulate the idea of natural selection when he saw how breeders could effectively change dogs and pigeons by identifying and accentuating certain traits through breeding. Equally, the population was expanding in Britain at the time, and in 1834 a poor law was amended. This played a role in separating men and women to stop them breeding.

Darwin realized that the increase in the population had lead to a lack of resources. And, with more mouths to feed there was less to go around. It occurred to Darwin this competition would ultimately weed out the unfit and it was when he applied this idea to nature that he had formulated the basis of a theory that would forever change the way we view life on earth.

Darwin took 20 years to publish The Origin of the Species, which would go into great detail to explain the theory of natural selection. He had seen so much on his voyage, he undoubtedly found it difficult to find the time to condense his experiences into proofs that would back-up his theory. He did however produce a 230-page abstract of his theory in 1842 and would expand that to a 300-page paper in the summer of 1844. Darwin revised his ideas over the course of those two decades and added to them as he came across new evidence and information.

An Intellectual and Conceptual Revolution

When he finally published The Origin of The Species with its explanation of natural selection, without reference to God, a higher power or a creator, it changed the way scientists looked at evolution. According to the eminent late evolutionary biologist Ernst Mayr, "Eliminating God from science made room for strictly scientific explanations of all natural phenomena; it gave rise to positivism; it produced a powerful intellectual and spiritual revolution, the effects of which have lasted to this day."[6]

More than just something that changed the world of science, the notion man, animals and plants were effectively descending from the same replicable cell is something that is very difficult to put into perspective even nowadays. Man, the ruler of the world, the smartest of creatures, the creator of art and music was not born superior from the outset, but equal. This thought was unbearable to many at the time and that is no surprise. The famous depictions of Darwin as a monkey that appeared on newspapers such as The London Sketch-book and in satirical magazines like La Petite Lune appear to us nowadays as testaments of fear and disbelief.

This moment in history is capital: man’s status amongst all things, was, once again, completely downsized. It is reminiscent of when Galileo told the world the Earth was not the center of the universe but only one of the many planets orbiting the larger sun. Man has always had an idea of itself as more important in the order of things and realizations that point to its smallness and insignificance always come as a shock.

The presence of God to explain the way the world and humanity came about is comforting -it elevates man to a higher level. In the book of Genesis God says: "Let Us make man in Our image, according to Our likeness; and let them rule over the fish of the sea and over the birds of the sky and over the cattle and over all the earth, and over every creeping thing that creeps on the earth."[7] How wonderful to think that man is equated to God and was born to rule the Earth and all the creatures on it. Darwin wipes all of this away and leaves us to face a cold reality: scientifically we are nothing more than a conglomeration of cells which just happened to evolve differently to other plants and creatures. How about that for a paradigm shift in perception?

Did you enjoy this article? If so, tell the world! Tweet about it, like it, or share it by clicking on one of the buttons below!

Finally, you can track all the stops and events of Darwin’s voyage of the Beagle in the infographic available here.

1. http://darwinbeagle.blogspot.co.uk/2007/07/3rd-july-1832-comments-on-slavery-in.html

2. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ichneumonoidea

3. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20665232

4. http://www.faithology.com/biographies/charles-darwin

5. http://www.faithology.com/biographies/charles-darwin

6. http://www.independent.co.uk/news/science/the-big-question-how-important-was-charles-darwin-and-what-is-his-legacy-today-1216258.html

7. The Parallel Bible (Peabody MA: Hendrickson Publishers, 2009), p. 2.

Charles Darwin as a monkey in The London Sketch-book (1874).

Charles Darwin depicted as a monkey on a tree in La Petite Lune (1878).