Steve Strathmann considers what the three presidents most closely associated with World War II did during that other great war of the twentieth century – World War I.

In 1917, Woodrow Wilson led the United States as it entered the First World War. In his speech to Congress asking for a declaration of war, Wilson presented Germany’s submarine warfare as the primary reason to go to war, but he also stated a greater goal:

The world must be made safe for democracy. Its peace must be planted upon the tested foundations of political liberty. We have no selfish ends to serve. We desire no conquest, no dominion. We seek no indemnities for ourselves, no material compensation for the sacrifices we shall freely make. We are but one of the champions of the rights of mankind. We shall be satisfied when those rights have been made as secure as the faith and the freedom of nations can make them.

The two men who held the office before him supported the nation’s entry into the war. Theodore Roosevelt, a veteran of the Spanish-American War, asked to personally raise a division of troops to be sent to Europe. Wilson met with Roosevelt and politely declined the offer, explaining that the ranks would be instead filled through a draft. Another strike against Roosevelt going to Europe was his poor overall health; he would barely outlive the conflict, passing away on January 6, 1919.

William Howard Taft spoke publicly in support of the war. On June 13, 1917, he repeated Wilson’s “war for democracy” theme, declaring “...Now we have stepped to the forefront of nations, and they look to us.” Taft would be tapped by President Wilson to chair the National War Labor Board, a panel set up to handle labor/management disputes during the war.

While other future presidents would make contributions to the war effort (especially Herbert Hoover, whose work during and after the war would make him internationally famous), what did the three presidents most identified with the Second World War do in 1917? As we shall see, these three men all served their nation’s military in different ways.

The Assistant Secretary

FDR, with Secretary Daniels and the Prince of Wales, in Annapolis, 1919.

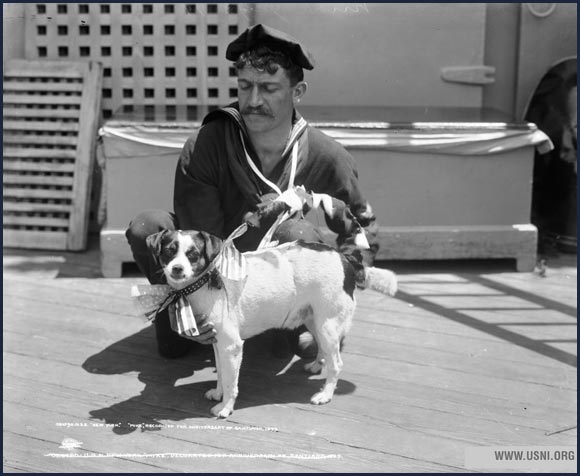

While the war raged overseas, Franklin Delano Roosevelt (Theodore’s cousin) was a member of the Wilson administration serving as the Assistant Secretary of the Navy. At the start of war, Roosevelt publicly called for an increase in the size of the US Navy by 18,000 men. This got him into trouble with Wilson and Navy Secretary Josephus Daniels, who were trying to maintain a state of neutrality. Roosevelt had to recant his statement, and learned not to step on his superiors’ toes.

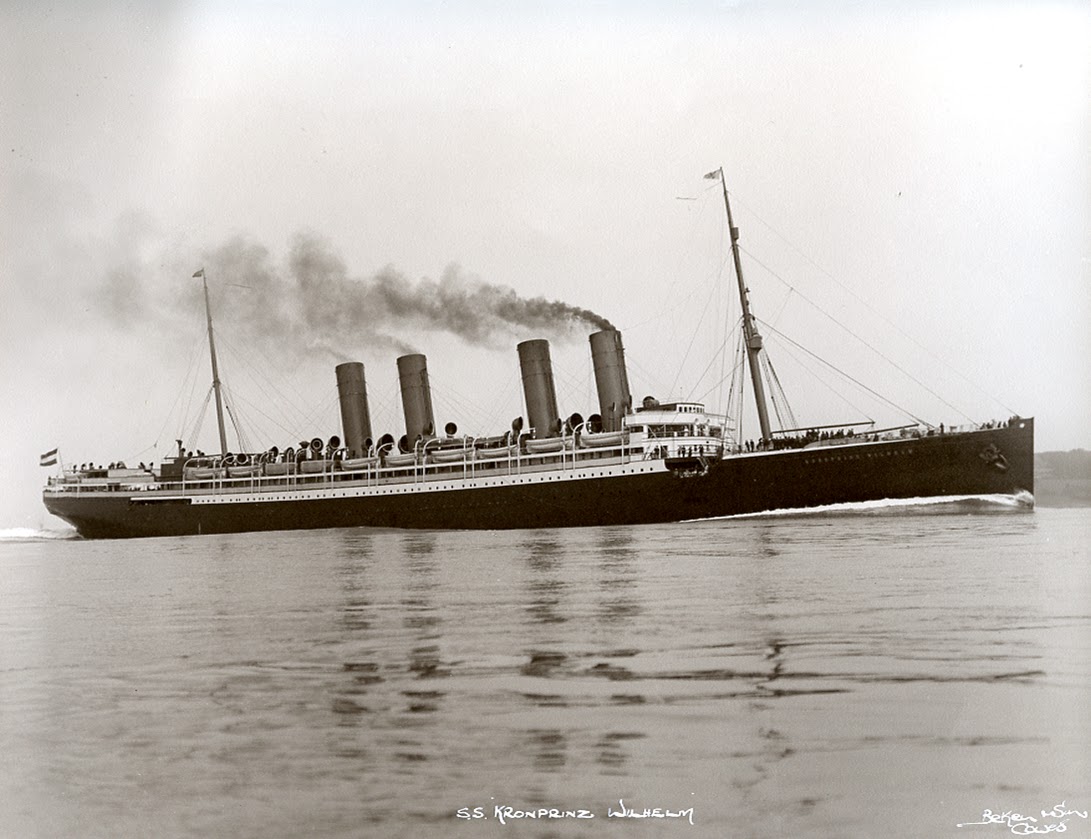

By July of 1915, the administration was coming into line with Roosevelt’s beliefs on naval expansion. Increased action in the Atlantic Ocean, including the sinking of the Lusitania, convinced Wilson that the military needed to be updated and enlarged to improve the nation’s defenses. Daniels and FDR presented a plan calling for the construction of 176 new ships, including ten battleships. This was approved by the president and Congress.

Even with these preparations, the US Navy was relatively small when war was declared. This had changed by the end of the war, when the force had expanded to almost a million sailors on over 2,000 vessels. Roosevelt had a hand in this, proving to be so good at gathering military supplies that he had to be asked to share the navy’s material gains with the army.

According to biographer Jean Edward Smith, FDR’s greatest wartime work was the creation of a North Sea antisubmarine chain of mines. While the initial plan was not Roosevelt’s, his promotion of the idea and the technology to accomplish it was what led to it being implemented. The chain wasn’t installed until the summer of 1918 and it was never fully tested, but estimates of German U-boats destroyed by the mines range from four to as many as twenty-three.

Above all, Franklin Roosevelt wanted to serve in the military during the war. He knew how his cousin’s military exploits helped with his political career and wanted to follow in his footsteps. Theodore Roosevelt even encouraged Franklin to enlist. Unfortunately for FDR, his talents working for the administration meant that Wilson and Daniels would never let him leave his post.

Roosevelt did eventually make it to the Western Front, but not as a soldier. In the summer of 1918, he was sent as part of a Senate committee to inspect the situation in Europe. He insisted on going to the French battlefields, including Verdun and Belleau Wood, and came within one mile of the German front lines. Little did he know, his future vice president was serving in an artillery unit not too far away.

Captain Harry

Harry S. Truman in France, 1918.

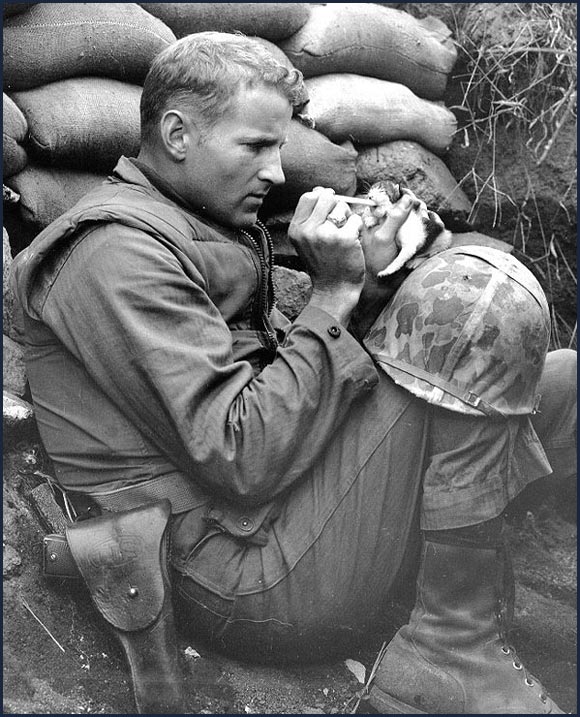

Harry S. Truman volunteered when war was declared, and the former Missouri Guard member was elected an officer in the artillery formations being organized in the Kansas City/Independence region. After training in Oklahoma, the units sailed for France, arriving on April 13, 1918.

On July 11, Truman took over command of Battery D. The battery had had issues with their previous commanders, but Truman soon earned their respect. Indeed, according to author Robert Ferrell, these soldiers would in the future be Truman’s political base, willing to do anything to support the man they called “Captain Harry.”

Truman’s battery saw action in the Vosges Mountains, Meuse-Argonnes and Verdun. Before Meuse-Argonnes, the captain marched his battery for twenty-two nights to reach their destination. During the two weeks there, Truman’s men sometimes fired their guns so often that, according to the battery’s chief mechanic, “...they’d pour a bucket of water down the muzzle and it’d come out of the breach just a-steaming, you know.”

Verdun was a particularly grizzly posting. The area where the unit was stationed was part of the 1916 battlefield, so every shell that landed around the battery would churn up graves from the previous action. Truman would describe waking up in the morning and finding skulls lying nearby. The battery would serve at Verdun until the end of the war.

While Truman was learning to become a leader of men under fire, one of his future generals was fresh out of West Point, desperate to join in the action, but continually thwarted in his attempts.

Ike

Dwight D. Eisenhower, with tank, in Fort Meade.

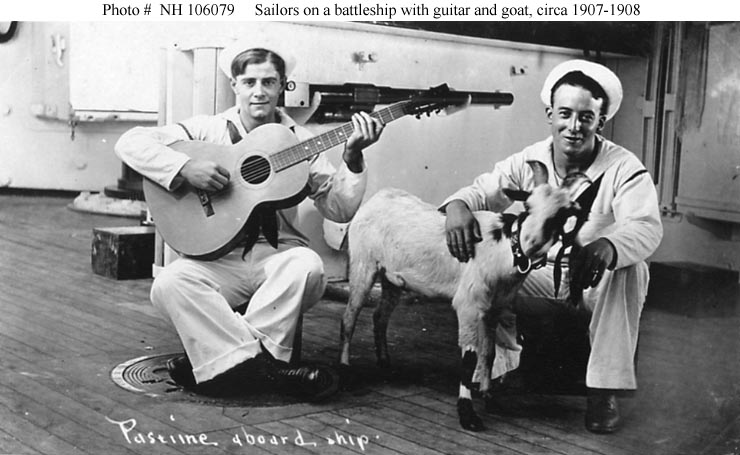

Dwight D. Eisenhower graduated from West Point in 1915, sixty-first in a class of 164. Despite his wishes to be posted in the Philippines, he ended up in Texas. When the United States entered the war, Eisenhower was appointed regimental supply officer of the new 57th Regiment.

Unfortunately for the ambitious Ike, he proved to be an excellent training officer and was turned down every time he requested a transfer to Europe. Like Roosevelt, he was too valuable to let go. He was soon transferred to Fort Meade to help organize the 301st Tank Battalion, one of the United States’ first tank units. He was supposed to leave for France with the 301st as its commander, but at the last minute was told that he would remain behind (once again) to set up a training base, Camp Colt, to be located on the old Gettysburg battlefield in Pennsylvania.

Eisenhower did a fantastic job setting up Camp Colt, which soon held more than 10,000 men training on the site of Pickett’s Charge. Due to a lack of tanks, they would use guns mounted on flatbed trucks to practice firing at targets while in motion. Finally all was going well and Eisenhower was scheduled to leave for Europe with the next group of recruits, but the war ended just as they were preparing to leave.

War to End All Wars?

As the war ended, these three men probably thought what most others did: this war was the last of its kind to be fought. Eisenhower would remain in the army. Truman would return to Missouri and try his hand in business. Roosevelt would continue in politics, running for vice president on the unsuccessful 1920 Democratic ticket. Little did these three men know that they were destined to meet in just over a couple of decades, fighting the next world war.

If you enjoyed this article, tell the world. Tweet about it, like it, or share it by clicking on one of the buttons below!

References

Aboukhadijeh, Feross. "U.S. Entry into WWI" StudyNotes.org. StudyNotes, Inc., Published November 17, 2012. Accessed May 16, 2014.

Duffy, Michael, ed. “Primary Documents- U.S. Declaration of War with Germany, 2 April 1917.” FirstWorldWar.com. Published August 22, 2009. Accessed May 16, 2014.

Duffy, Michael, ed. “Primary Documents- William Howard Taft on America’s Decision to go to War, 13 June 1917.” FirstWorldWar.com. Published August 22, 2009. Accessed May 16, 2014.

Ferrell, Robert H. Harry S. Truman: a life. Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press, 1994.

Korda, Michael. Ike: An American Hero. New York: Harper, 2007.

Smith, Jean Edward. FDR. New York: Random House, 2007.

Photos

http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/npc2007000705/resource/ (FDR, with Secretary Daniels and the Prince of Wales, in Annapolis, 1919)

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Harry_S._Truman_WW_I.jpg (Harry S. Truman in France, 1918)

http://www.ftmeade.army.mil/museum/Eisenhower_with_Tank.jpg (Dwight D. Eisenhower, with tank, in Fort Meade)