Step Right Up!

“There’s a sucker born every minute” is a phrase which continues to live its wrongfully folkloric life as having been fathered by P. T. Barnum, the greatest showman on earth and four-term Connecticut legislator whose abolitionist ideals led him to switch allegiances from the Democratic Party to become a sworn Lincoln Republican.

Though the origin of the aphorism is believed to trace instead to David Hannum, who financed the exhibition of the alleged ten-foot tall mummified remains of the ‘Cardiff Giant’ in 1869 and took great exception to Barnum’s simultaneous display of a mold he had made and passed off as the real deal (a fake of a fake), journalist and Gangs of New York author Herbert Asbury attributes the saying in his 1940 book Gem of the Prairie: Chicago Underworld to Michael Cassius McDonald. A charismatic Irish immigrant whose four-story gambling house ‘The Store’ was often referred to as Chicago’s “unofficial City Hall”, McDonald is said to have uttered the immortal words to calm the nerves of his business partner Harry Lawrence over his concern as to how they could possibly attract enough of the Windy City’s inhabitants to patronize their establishment. Wielding great enough influence, both criminal and political, he formed a syndicate known as McDonald’s Democrats which strong-armed the mayoral election of 1879 in the direction of Carter Harrison Sr., a distant cousin of President William Henry Harrison.

Politics and show business have long been cozy bedfellows. There are carnival-like elements inherent to campaigns, conventions, and elections which rub shoulders with those of traveling ten-in-one sideshows and three-ring, big-top circuses of old. So, it seems only natural that both of 1960’s presidential aspirants would invoke similarly germane imagery as the election cycle wound down through the home stretch.

“The people of the United States, in this last week, have finally caught up with the promises that have been made by our opponents,” said Vice President Richard Nixon from the steps of Oakland’s City Hall on a windswept November 5. “They realize that it’s a modern medicine-man show. A pied piper from Boston and they’re not going to go down that road.”

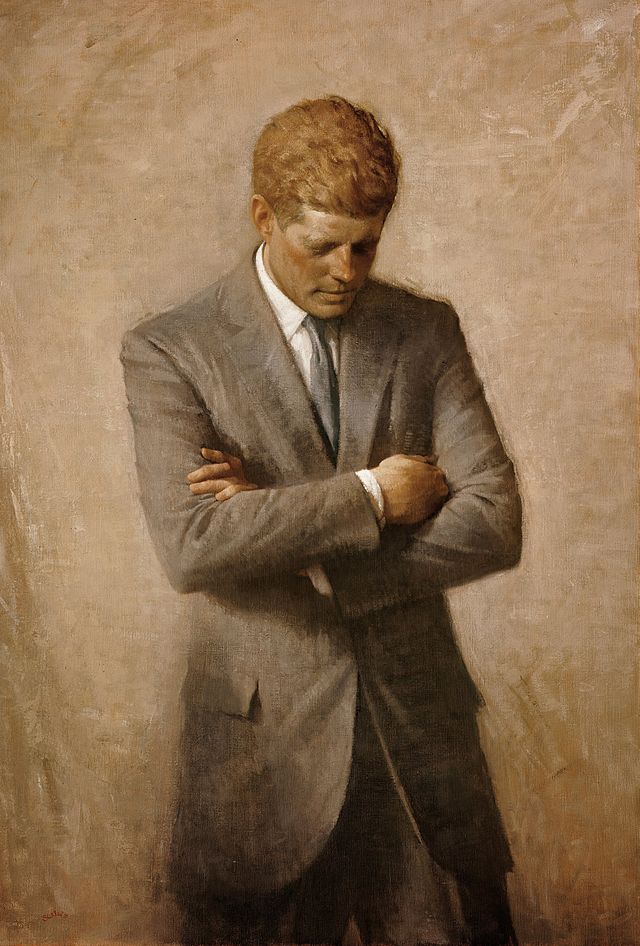

John F. Kennedy, meanwhile, speaking before a frenzied constituency at the Boston Garden two days later, took the analogy one step further by quipping, “I run against a candidate that reminds me of the symbol of his party. The circus elephant, with his head full of ivory, a long memory, and no vision. And you have seen elephants being led around the circus ring. They grab the tail of the elephant in front of them.”

The Religion Issue

Not since anti-Prohibitionist New York Governor Alfred E. Smith in 1928 had there been a Catholic nominee for the U.S. presidency. While it may be difficult today to fathom what a substantial stumbling block this presented then to upwardly mobile politicians, the very notion of a non-Protestant potentially merging church and state was very real and simply unthinkable, making Kennedy’s Catholicism an allegorical cross to bear. So much so that his Press Secretary Pierre Salinger recalls attempting to enlist the staunchly conservative Reverend Billy Graham to aid their cause during a train ride from West Virginia to Indianapolis.

“We were in the process of trying to get the nation’s leading Protestant churchmen to sign a public statement urging religious tolerance in the political process,” Salinger said. After initially promising his signature to the document’s final draft, Kennedy confidante and speechwriter Ted Sorensen later received a far less amenable response, in the form of “a flat-out no”, remarking that it would be wrong “to interfere in the political process.” Salinger noted that “later that year, however, Graham appeared at a number of political rallies for Richard Nixon. Apparently, it would have been wrong to interfere in the political process on behalf of a Democrat.”

Forced to directly confront the issue, Kennedy addressed the Greater Houston Ministerial Association, not to mention the nation at large, on September 12, 1960.

“Contrary to common newspaper usage, I am not the Catholic candidate for President”, he stated in clear defiance without the tone of agitated self-defense. “I am the Democratic Party's candidate for President, who happens also to be a Catholic. I do not speak for my church on public matters, and the church does not speak for me.”

The Red Menace

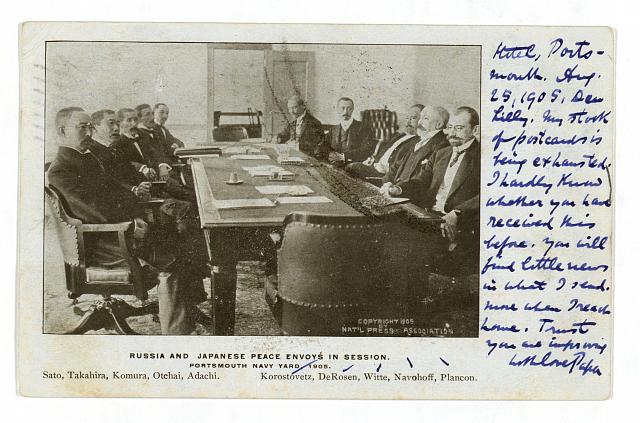

With the domino theory put in place in the 1950s and threatening to set off a chain reaction of toppled democracies across the map, replaced by Communist adherents to the tenets of Marxism-Leninism, the incoming Commander-in-Chief would be expected to deal assertively with the bogeymen of the “red scare” in the forms of South Vietnam’s Ngo Dinh Diem, Castro in Cuba, and particularly First Secretary of the Soviet Union, Nikita Khrushchev.

Nixon had earned a reputation as a hard-liner in the struggle to seek and destroy socialist tendencies with tough words and even tougher endeavors. First serving as legal counsel on Joseph McCarthy’s House Un-American Activities Committee, he became a household name for his successful prosecution of Communist spy Alger Hiss in 1948. It was suggested that Hiss represented all that Nixon despised. Wealthy, liberal, Harvard-educated, and handsome. Sound familiar?

Senator Kennedy was persistently needled as being “soft on Communism” by Nixon, who had slapped his 1950 Senatorial opponent Helen Gahagan Douglas with the libelous epithet “pink lady” for her New Deal progressiveness and references to HUAC as a “smear organization”. Interestingly enough, in 1950 Kennedy, his father Joe an anti-Communist McCarthy crony, privately supported Nixon. “I obviously can’t endorse you,” he admitted, “but it isn’t going to break my heart if you can turn the Senate’s loss (Douglas, herself a former actress) into Hollywood’s gain.”

Khrushchev, who would go toe-to-toe with Kennedy during the Vienna Summit, Cuban Missile Crisis, Berlin Wall standoff, and Test Ban Treaty, offered this after-the-fact personal assessment of both candidates in his memoirs. “I was impressed with Kennedy. I remember liking his face which was sometimes stern but which often broke into a good-natured smile. As for Nixon...he had been a puppet of Joseph McCarthy until McCarthy’s star began to fade, at which point Nixon turned his back on him. So, he was an unprincipled puppet, which is the most dangerous kind,” he wrote. “I was very glad Kennedy won the election... I could tell he was interested in finding a peaceful solution to world problems and avoiding conflict with the Soviet Union.”

Civil Rights

An initial Kennedy backer until he felt snubbed during a personal meeting and came to the conclusion that the Democrat was unwilling to move forward on civil rights issues, retired Brooklyn Dodger and destroyer of baseball’s color barrier Jackie Robinson campaigned instead for the Republican nominee but bemoaned the fact that “the Negro vote was not at all committed to Kennedy, but it went there because Mr. Nixon did not do anything to win it.”

Kennedy, in a letter to Eleanor Roosevelt who was pushing the reluctant Senator into progressive action in courting the support of the black community, wrote, “With respect to Jackie Robinson… he has made uncomplimentary statements to the press about me,” sulking that, “I know that he is out to do as much damage as possible.” Nixon’s running mate Nelson Rockefeller, with Robinson’s blessing, was eventually called upon to espouse the ticket’s fidelity to civil rights in what was considered a too-little, too-late effort.

Kennedy, meanwhile, placed a conciliatory phone call to Coretta Scott King following the arrest of her husband Martin and fifty-two fellow protestors staging a sit-in at the Magnolia Room of Rich’s Department Store in Atlanta. Sentenced to four months of hard labor after all others involved had been released, Martin Luther King was freed only when news of Kennedy’s gesture, as well as brother Robert’s personal intervention on King’s behalf, reached the Georgian judge who had presided over the case. “Because this man was willing to wipe the tears from my daughter’s eyes,” said an emotional King, “I’ve got a suitcase of votes and I’m going to take them to Mr. Kennedy and dump them in his lap.”

It is worth noting that these maneuvers on the part of the Kennedy brothers carried more than a slight whiff of patronizing opportunism and that, although the both of them did evolve dramatically and genuinely in later years on race relations, it was a birthing process which was painful and sluggish.

The Debates

“Without the many panels and news shows, without his shrewd use of TV commercials and telecast speeches, without television tapes to spread wherever needed his confrontation with the Houston ministers, without the four great debates with Richard Nixon, John Kennedy would never have been elected President,” asserted Ted Sorensen.

Though they squared off four times (Kennedy lobbied fruitlessly for a fifth), it was the first on September 26, 1960 in Chicago’s CBS Studios which proved to be as visually revealing as it was historically significant. The first ever televised presidential debate, the new medium did Nixon no favors. Having just been released from the hospital after the knee he injured on the campaign trail had become dangerously infected, the Vice President, underweight and sporting a five o’clock shadow, was still susceptible to feverish sweats and a sickly complexion which may have been alleviated somewhat had he not refused a cosmetic touch-up. Nixon’s poor physical appearance was augmented by his unfortunate choice of a grey suit which was ill-fitting and represented poorly in black and white against the studio’s similarly drab backdrop.

Contrasted against Kennedy’s navy blue suit, copper-colored tan, and million dollar smile, Nixon staggered into a situation which found him already at a decided disadvantage. Like college kids cramming for an exam, Kennedy went through hours of dry runs with Sorensen and Salinger and his levels of confidence and preparedness were evident for all to see. Falling back on practices learned while starring on Whittier College’s esteemed debate club, Nixon continually addressed Kennedy personally, looking away from the television cameras to do so, appearing anxious and adversarial. Poll results differ to this day, but most seem to suggest that the two combatants were evenly matched in terms of verbal content as heard by radio listeners which was betrayed by the pair’s physical incongruities visible to home viewers.

One person who concurred was Nixon’s own running mate Henry Cabot Lodge who remarked, “That son of a bitch just lost the election.”

First Ladies

On assignment for the April 1953 edition of the Washington Times-Herald, their Inquiring Camera Girl Jackie Bouvier interviewed both Vice President Richard Milhouse Nixon and newly elected Massachusetts Senator John F. Kennedy. Jack and Jackie had been quietly seeing one another since a dinner party the year before where, as then-Congressman Kennedy recalled, “I leaned across the asparagus and asked for her for a date.” Their relationship attained a public profile in January 1953 when the Hamptons-born beauty (with brains to match) accompanied Kennedy to Dwight Eisenhower’s inaugural ball. Pregnant with John Jr. and confined to bed rest for much of the 1960 campaign, Jackie may not have been an observable presence, but did contribute in the way of a syndicated newspaper column called Campaign Wife which combined personal anecdotes with political affairs, as well as handling correspondence and giving interviews.

Pat Nixon, on the other hand, was never far from Richard’s side, or the public consciousness. A “Pat For First Lady” movement gained strength among the schoolteachers and housewives to whom she tailored her message, and her likeness could be seen on nearly as many buttons and bumper stickers as that of her husband. An attempt was even made in the press, ill-conceived and ill-fated, to manufacture a race for First Lady between Pat and Jackie based on clothing choices as much as, if not more than, party platform.

Dismissed by Mamie Eisenhower as “that woman” for her inimitable fashion sense, Jackie, in turn, took a catty swipe at her 1960 rival for First Lady by telling historian and Kennedy think-tank member Arthur Schlesinger Jr. that Jack “wasn’t thinking of his image, or he would have made me get a little frizzy permanent like Pat Nixon.”

Postlude

Both men would, of course, achieve the Presidency. Nixon not until 1968, and only after the path had been paved by Lyndon Johnson’s concession to neither seek nor accept his party’s nomination as well as the assassination of Robert Kennedy a mere four and a half years after his own brother, on that fateful November day in Dallas, was made a national martyr on equal footing, in the hearts and minds of generations of Americans, with the beloved Abraham Lincoln.

All of this calls to mind something P. T. Barnum actually did say. “You have to throw a gold brick into the uncertain waters of the future, and faith because there will be many difficult days before you will see the returns start rolling in.”

Did you enjoy this article? If so, do feel free to share it! Like it, tweet about it, or share it by clicking on one of the buttons below…

And remember… You can read Chris’ article on JFK and Eleanor Roosevelt in the 1950s by clicking here.