World War I is of course one of the most important wars in modern history, and of the key geo-political aspects of the war was the formation of the Triple Entente between Britain, France, and Russia. These Great Powers with overlapping interests were not necessarily natural allies in World War One, but the nature of international affairs in the preceding decades pushed them together.

Here, Bilal Junejo starts a series looking at how the Triple Entente was formed by considering the impact of the formation of the German nation in 1871 on other European countries. In particular, Austro-Russian tension in the Balkans and Franco-German tension on the Rhine, and a paranoia in Berlin is considered.

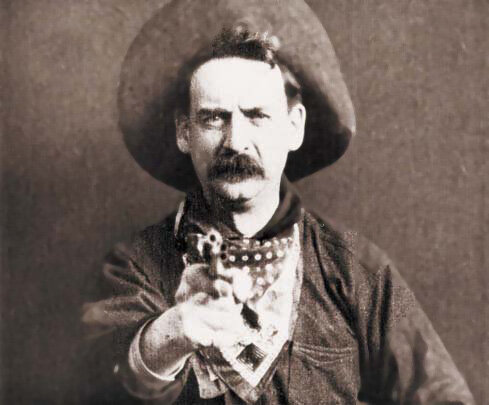

Otto von Bismarck, a key person in the early days of the German nation.

The outbreak of the First World War in 1914 remains, to date, one of the most formidable events in the entire history of mankind. The world, as we presently know it, owes the greater part of its lineaments to that carnage which pervaded Europe and her many empires for four years, and the (happy) abortion of which drastic upheaval might have resulted in contemporary atlases manifesting radically different features from those that happen to adorn it today. By 1918, many empires had evaporated and new states emerged in their stead; older powers were humbled and eventually supplanted by newer and bigger ones. The process that commenced in 1914 reached its apotheosis in 1945, when the losers of the First World War— who had fought in the Second specifically to reverse the verdict of the First— emerged as losers of the Second as well, but not before ensuring that the penalty of their misadventures exacted tribute from the victors too, since 1945 also marked the end of a whole era— the age of a world order dominated by Europe. What emerged in its wake was a bipolar, and infinitely more rigid, international system that lasted until the collapse of the redoubtable Soviet Union in 1991.

However, there was nothing inevitable about the Cold War, for all that happened post-1945 was largely determined by what had happened pre-1945 (or, to be more precise, post-1918). And what happened post-1918 was again determined by what had transpired prior to that time, particularly since 1871. This is by no means a year chosen at random, for, with the indispensable benefit of hindsight, this was the twelvemonth in which, it can reasonably be argued, the seeds of the ultimate downfall of Europe were sown. What came to pass in 1914 was caused directly, inasmuch as one event leads to another, by what had happened in 1871; but what happened post-1918 was determined in conjunction with what had transpired during the War itself, from 1914 to 1918. But, it should not be forgotten that the motives which precipitated World War I— avarice and/or fear, such as have animated just about every war waged in human history— had little or nothing to do with the magnitude of the conflagration that ensued, and subsequently engulfed the world. What was different in 1914 from any previous time in history were the means available, and the scale consequently possible, for the purpose of waging war. The formidable achievements that had been made in military technology since the advent of the Industrial Revolution in the eighteenth century, and the vast colonial resources that were available to each of the Great Powers to realize the full potential of the technology at their disposal (indeed, it was primarily the existence of vast colonies and empires that had turned an essentially European war into a World War), ensured that even the slightest insouciance on anyone’s part would engender a maelstrom that would consume everything until there was nothing further left to consume. Given the exorbitant cost that was almost certain to attend any impetuous escapade, it becomes any thoughtful soul gazing down the stark and petrified roads of time to ask how the ends justified, if they ever did, the means. To recall the jibe of Southey:

“And everybody praised the Duke,

Who this great fight did win.”

“But what good came of it at last?”

Quoth little Peterkin.

“Why that I cannot tell,” said he,

“But ‘twas a famous victory.”

A short war?

Why did the European powers decide to appease Mars, at the woeful expense of Minerva, in that fateful year? Was it out of sheer necessity, or mere audacity? Possibly, the answer lies somewhere in the middle. Every war invariably stipulates a certain boldness that must be exuded by the participants, since it is humanly impossible to guarantee the outcome of any conflict, let alone one in which weapons capable of unleashing destruction and havoc on a colossal scale are to be employed. When war broke out in 1914, there was a wave of joy that swept through each of the belligerent countries, even though their respective governments did not exactly share that enthusiasm. Maybe this seemingly inexplicable effusion was owing to a misapprehension that the war would shortly culminate in a decisive victory— a reasonable enough supposition, since a World War, by definition, remained without precedent till 1914. Even the statesmen of the various countries involved did not anticipate anything like what eventually came to pass, a notable exception being the British Foreign Secretary, Sir Edward Grey, who presciently, if sadly, prophesied on the eve of the conflict that:

“The lamps are going out all over Europe— we shall not see them lit again in our lifetime.”

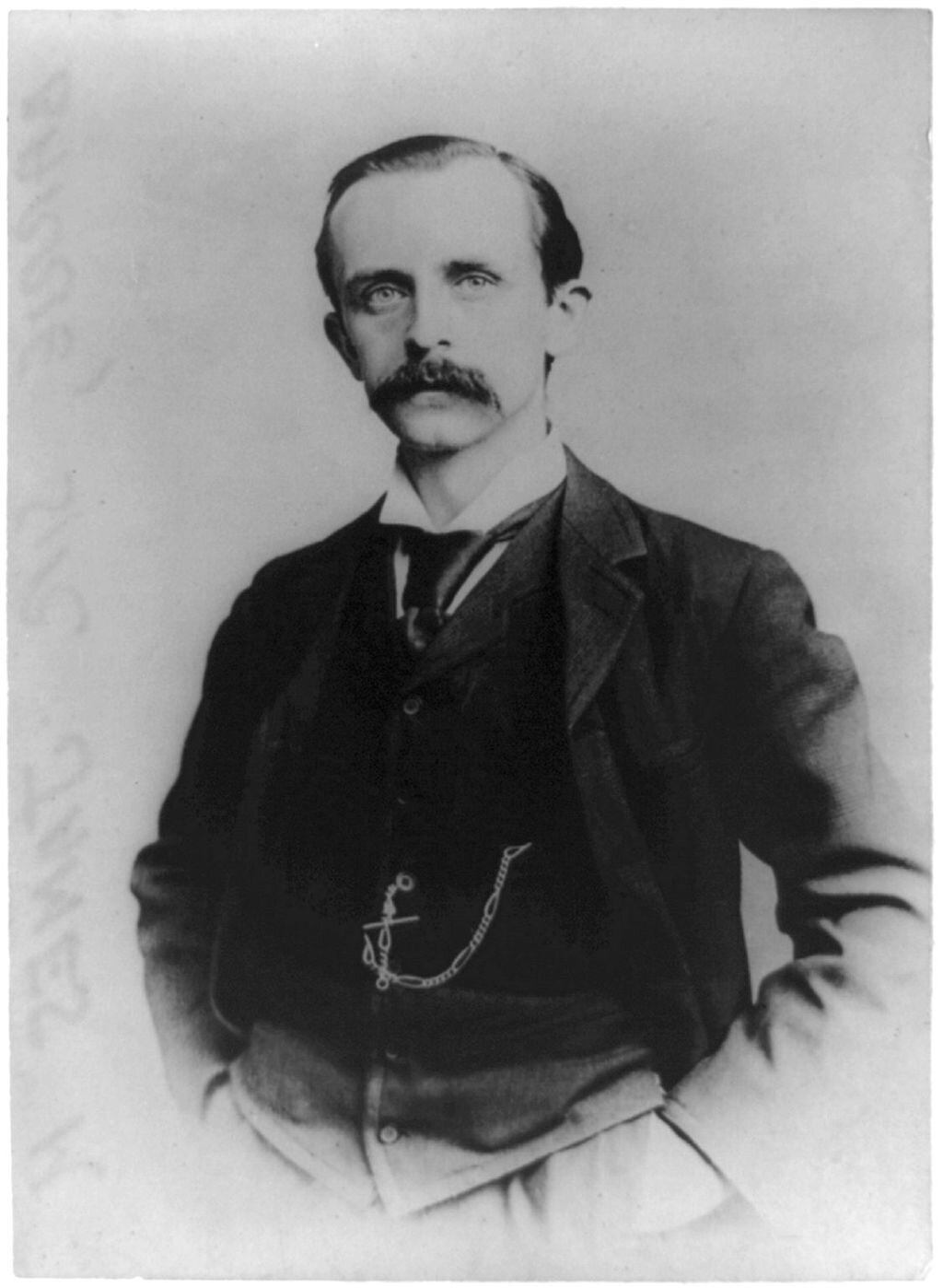

The popular mood, however, was depicted more accurately by the last lines of His Last Bow, one of the many Sherlock Holmes stories penned by the estimable Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. Although possibly a piece of propaganda to boost public morale, given that it was published after three years of savagery in September 1917, the lines in question, notwithstanding the palpable pathos they garner from the fact that both Holmes and Watson— proverbial for their friendship— are about to go their separate ways on the eve of war, are still notable for their espousal of, and patent lack of any regret for, war.

“There’s an east wind coming, Watson.”

“I think not, Holmes. It is very warm.”

“Good old Watson! You are the one fixed point in a changing age. There’s an east wind coming all the same, such a wind as never blew on England yet. It will be cold and bitter, Watson, and a good many of us may wither before its blast. But it’s God’s own wind nonetheless, and a cleaner, better, stronger land will lie in the sunshine when the storm has cleared.”

Why were the peoples of Europe so bellicose in 1914? A cogent rejoinder was tendered by the perspicacious Doctor Henry Kissinger, when he observed:

“In the long interval of peace (1815-1914), the sense of the tragic was lost; it was forgotten that states could die, that upheavals could be irretrievable, that fear could become the means of social cohesion. The hysteria of joy which swept over Europe at the outbreak of the First World War was the symptom of a fatuous age, but also of a secure one. It revealed a millennial faith; a hope for a world which had all the blessings of the Edwardian age made all the more agreeable by the absence of armament races and of the fear of war. What minister who declared war in August 1914, would not have recoiled with horror had he known the shape of the world in 1918?”

The Triple Entente

Even if the people felt ‘secure’ and animated by a ‘millennial faith’, could it be said that their respective governments also felt exactly the same way? Was there not even the slightest degree of compulsion that was felt by the statesmen of each belligerent nation as they embarked upon war? It seems that but for one glaring fact, the answer could have been readily given in the affirmative. That fact is the nature of those alliances into which the Great Powers were firmly divided by 1914. On the one hand, there was the Triple Alliance of Germany, Austria-Hungary and Italy; on the other, there was the Triple Entente of Great Britain, France and Russia. The rearrangement of some loyalties during the war, with corresponding additions and subtractions, lies beyond the purview of this essay, the sole purpose of which is to illuminate international perceptions as they existed prior to the outbreak of war. And it is in the realm of these perceptions that the cynosure of our discussion today is to be found, for there was something inherent in the Triple Entente that was very untoward and, consequently, very ominous. It was the fact that the Entente— a precise and deliberate reaction to the creation of the Triple Alliance— had come into being between sovereign states who were anything but natural allies of each other! Each of the three parties thereto was, for reasons to be canvassed later, an object of immense detestation to the others, so to whom must the credit for so unnatural a coalition be given? The answer is immediately clear— Imperial Germany. With its acutely myopic foreign policy, pursued unfailingly, from 1890 to 1914, it succeeded, however inadvertently, in ranging three very unlikely allies in an association aimed solely against itself.

Every war, it must be remembered, has both immediate causes and distant causes. In the case of the First World War, the former are ascertained by asking why did the War break out at all in the first place; whereas the latter by asking why did it break out in 1914. We shall review both of these questions, but it is by dint of this peregrination that you shall assure yourself of how the same impetus that had precipitated so aberrant an association as the Triple Entente in the first place, was also responsible for its ineluctable clash with the Triple Alliance, since nothing but the keenest awareness of an overwhelming peril in their neighborhood could have convinced such inveterate foes as London, Paris and St Petersburg to settle their mutual differences and together strive for the attainment of a common, to say nothing of congenial, end— the defeat of Germany. In this article, we shall confine ourselves to a succinct examination of the new European order (and its irrefragable hallmarks) that emerged in 1871. Since the Entente came about by way of reaction to the Triple Alliance of 1882, which was itself a natural consequence of this new order, it behooves us to first comprehend the origins of this order, before proceeding to contemplate how it influenced the advent of that century’s most portentous dichotomy.

The birth of modern Germany

To begin, it was the year 1871 that marked the birth of the new Germany. Up till that point in time, no such entity as a united Germany had existed. A myriad of states dotted the landscape to the east of France, north of Austria and west of Russia. Naturally endowed with every blessing that was the prerequisite of a Great Power in the nineteenth century— a people who were at once proud and prolific, vast natural reserves of coal and iron, and a position of geopolitical eminence in the center of the Continent— the German peoples north of a decrepit and declining Austria only needed a leadership of iron will and indomitable resolve to sweep away that panoply of effete princelings who still hindered the destined unity of an ancient race by dint of their endlessly internecine strife. And Providence favored the Teuton just then, for there arose a man whose impregnable personal convictions, filtered through his unmatched political acumen, were to forever change the course of European history. That man was none other than the formidable Otto von Bismarck, the founding father of modern Germany. Bismarck may not have been the first one to realize that a multitude of independent but moribund German kingdoms could never realize the dream of securing Great Power status for the German people, and that the course most favorable for its achievement would be a political union of all the kingdoms under the auspices of the strongest one of them, Prussia, which had become a major European power since the days of King Frederick II (1740-86); but he was certainly the one who demonstrated the veracity of that proposition beyond doubt. From the moment that he was appointed chief minister of Prussia in 1862, Bismarck set out to accomplish this stupendous goal that he had set himself with indefatigable perseverance. A statesman of unmatched astuteness, he perceived only too clearly for their own good which of his neighbors he had to humble before a tenable German Empire could be proclaimed. To that end, he waged three specific wars— against Denmark in 1864, Austria in 1866 and, finally, France in 1870. It is beyond the scope of this essay to delve into the particulars of those wars because what concerns us here are their political effects after 1871, when the Treaty of Frankfurt concluded the Franco-Prussian War by proclaiming the birth of Imperial Germany and the simultaneous demise of the Second Empire in France.

Liberalism and nationalism

At any given time in international relations, there are certain aspects that constitute constants, and certain that do variables. Just as the values of variables in a mathematical equation are determined by the constants that it entails, so also does it happen in the complex world of diplomacy and foreign policy, that the issues which lie beyond negotiation greatly circumscribe the range of values that may be attributed to a particular variable. The provenance of a constant in any state’s foreign policy lies in that state’s raison d’être; whereas that of a variable lies in the ambitions pursued and expedients adopted by the state to seek maximum expression for that raison d’être. It so happened that the three wars fought by Bismarck’s Prussia in the 1860s furnished European diplomacy with two of its most fateful and unfortunate constants, which lasted with uncanny steadfastness until 1914 and thus rendered the outbreak of a general European war inevitable. But what were the circumstances that made the two outcomes so rigid and impervious to any variation whatsoever? In other words, what was it that made the two outcomes constants? The answer to that can be found in the two cardinal features of nineteenth century Europe that were the legacy of the momentous French Revolution— liberalism and nationalism. Throughout the period designated by the late Professor Eric Hobsbawm as the ‘long nineteenth century’— i.e. from 1789, when the Revolution in France broke out, to 1914— these were the two isms that together comprised the ubiquitous hope of the people and the ubiquitous fear of their rulers.

The age of empires, which are inherently based upon the generation of fear and the deployment of force, was gradually drawing to an end, and what was to supplant it would be a polity whose quintessence could already be discerned in the United States and the United Kingdom— democracy. A true democracy, owing to its very nature, is inherently opposed to organizing its society by dint of force, which means that it perforce must turn to the precepts of nationalism and liberalism for inspiration, with the former defining its borders and the latter its government. For this reason, the autocratic courts and chancelleries of Europe were already on edge by the time Bismarck added to their troubles with his decisive victories over a stagnant status quo and forever altered the European balance of power. Having thus ascertained the background and context in which his feats operated, it should now be easy for us to understand how the two constants that we alluded to earlier actually came into being.

The first of them arose as a result of the Austro-Prussian War (also known as the Seven Weeks’ War) in 1866. Bismarck’s earlier victory over the Danes had been the means for engendering this conflict, since a portion of the territory that he had gained in 1864 (Schleswig-Holstein) had been granted to Austria, subsequent allegations of maladministration against whom eventually furnished Bismarck with the pretext that he needed for going to war against her. In reality, the reason for wishing to humiliate Austria was the fact that she remained the oldest German power, far older than Prussia, in existence on the Continent, the Habsburgs having ascended the throne as long ago as 1273. Austria, therefore, could have no rivals amongst the multitudinous German kingdoms when it came to legitimacy and pedigree, but her empire was an exceedingly multi-ethnic one, with just about as many Magyars and Slavs as there were Germans. In an age permeated by the ideas of the French Revolution, such an entity could not last for very long, since if Bismarck were to succeed in establishing a pan-German confederation, then the march of international events would dictate that the Germanic parts of the Austrian Empire should merge with Germany; whereas the Slavonic ones with the principal Slavonic power, Russia.

Bismarck, however ironic it may sound, was not at all keen to orchestrate such a development, for it would have turned his whole policy upside-down. Rather than being the offspring of popular sentiment alone, the German Empire, when it was eventually born in 1871, had primarily resulted from consent by all the German kings outside of Austria to unite as one under the indubitable hegemony of the Hohenzollern King of Prussia, who became the German Emperor (or Kaiser). Had German Austria, which was overwhelmingly Roman Catholic, been allowed to merge with a Germany dominated by Protestant Prussia, then the decisive influence exercised by the latter would undoubtedly have been diluted, especially since the aforementioned credentials of legitimacy favored the hallowed Habsburgs, the Hohenzollerns only having become the Royal House of Prussia in 1701. However, this fateful decision to exude magnanimity towards Austria after her defeat eventually became the first step in the march towards World War I, for having been allowed to exist but permanently barred from any further expansion towards the north in German-speaking lands, and never given to any kind of overseas colonialism, Austria had only one place left in which to expand and thus keep up the pretense of still being a Great Power— the Balkans. Overwhelmingly Slavonic and partitioned between the equally moribund and crumbling Austrian and Ottoman Empires for centuries, the Balkans of a nationalistic nineteenth century determined not only the common, not to mention insuperable, enmity of the two alien behemoths in Slavonic lands with Russia, the champion of Panslavism, but also the most egregious flashpoint in Europe that could trigger an irrevocable catastrophe of monumental proportions at the behest of even the slightest provocation. And eventually, in 1914, it was a Balkan conflict that, owing to centuries of arrogance and paranoia, eventually transmogrified into the cataclysm of World War I (in which both Austria and Turkey fought together on the same side, against Russia, and all three collapsed from a mortal blow at the end). Thus, intractable Austro-Russian rivalry in the Balkans became one of the unfortunate constants in international relations from 1866-1914.

Germany and France

The second constant emanated from the Iron Chancellor’s triumph over the Sphinx of the Tuileries, the vainglorious Emperor Napoleon III of the French Second Empire (the First Empire designating the rule of his illustrious uncle, Napoleon Bonaparte). Up to the point of its categorical defeat in the Franco-Prussian War, France had been generally perceived as being the strongest power on the Continent, and the Emperor Napoleon III as engaged in plotting machinations supposed to be as ambitious as they were surreptitious (hence his sobriquet). Moreover, France’s foreign policy during the Second Empire had done little to endear the country to her neighbors. Great Britain, the historic rival of France and the dominant figure in whose political life from 1852-65 had been the overtly chauvinistic Palmerston, was not reassured by French imperial endeavors, which spanned the globe from Mexico to North Africa to the Far East. Moreover, the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869, which had been constructed by a French company headed by a French diplomat and engineer called Ferdinand de Lesseps, was greatly resented by London (which had taken no part in either the canal’s funding or its construction) because of its geopolitical importance. Standing at the crossroads between three continents, it was palpable in the age of empire that control of the Suez Canal meant control of Asia. For example, using this Canal meant that the distance from India to Great Britain was reduced by approximately 6,000 miles/9,700 kilometers (for both troops and traders). And for a predominantly mercantile people like the British, the more they could reduce the costs of their shipping to and from India, the more competitive would their goods become in the world market, and thereby improve profit margins all over. So Britain, at this time, had every possible interest in weakening France relative to its present standing. On the other hand, with regard to her eastern neighbors, France had stood by in unhelpful neutrality when Austria was defeated in two wars, first by the Italian kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia in 1859, and then by Prussia in 1866. Russia had been humiliated by France in the Crimean War (1854-56). And as for Italy, whose unification could not be complete without the expulsion of the French troops in Rome who guarded the Pope, her reasons for supporting Prussia in 1870 were as comprehensible as were Austria’s and Russia’s.

Thus, with all the Continental powers keen to usher in a deflation of her ego, it is not surprising that France should have received no support in a war which, most importantly of all, she had been imperious enough to initiate herself against an ascendant Prussia. But what came to matter even more than the war itself were the peace terms upon which it was concluded. Enshrined in the Treaty of Frankfurt (1871), these terms stipulated that France must cede Alsace and most of Lorraine in the north-east to Germany, pay an indemnity of around five billion francs to the Germans, and accept an occupation force in the country until the indemnity had been conclusively defrayed. Whilst the indemnity was paid soon enough, and the German army withdrawn accordingly, the seizure of Alsace-Lorraine (an area rich in natural deposits of iron) continued to remain a focal point of French resentment, which would only fester with the elapse of each year. Moreover, Bismarck, who had been as vindictive and punitive towards France as he had been lenient and magnanimous towards Austria, had chosen to proclaim the birth of the new German Empire from the hallowed Palace of Versailles, in the presence of all the German princes and upon the ashes of French pride. This manifest insult, coupled with the loss of Alsace-Lorraine, meant that henceforth (and up to 1914), France would be permanently available as an ally to any country in Europe that wished to wage a war against the newborn Germany, who, in turn, would be on an equally permanent lookout to nip the prospect of any such alliance in the bud. That this synergy of malice and paranoia on the Continent could betoken nothing better than what eventually deluged Europe in 1914 was eloquently illuminated by the late historian, Herbert Fisher, when he observed:

“During all the years between 1870 and 1914, the most profound question for western civilisation was the possibility of establishing friendly relations between France and Germany. Alsace-Lorraine stood in the way. So long as the statue of Strasbourg in the Place de la Concorde was veiled in crêpe, every Frenchman continued to dream of the recovery of the lost provinces as an end impossible perhaps of achievement— for there was no misjudgement now of the vast strength of Germany— but nevertheless ardently to be desired. It was not a thing to be talked of. ’N’en parlez jamais, y pensez toujours,’ advised Gambetta; but it was a constant element in public feeling, an ever-present obstruction to the friendship of the two countries, a dominant motive in policy, a dark cloud full of menace for the future.”

To recapitulate, the Europe that emerged after 1871, and lasted until 1914, bore three characteristics that were, sadly, as permanent as they were formidable: Austro-Russian tension in the Balkans, Franco-German tension on the Rhine, and (consequently) festering paranoia in Berlin. In so delicate a situation as now defined Continental affairs, and one which had been entirely of his own making, Otto von Bismarck would henceforth have to summon the services of all the diplomatic finesse and chicanery that could be proffered by his scheming mind, and which was the only force capable of staving off the consequences that inevitably follow in the wake of a rival’s bruised ego. That his worst fears for Germany were not realized until after his unfortunate dismissal in 1890 remains a testament to the fact that something went very wrong in the succeeding twenty-four years.

We shall turn our full attention to this after we have canvassed the marvels of Bismarckian diplomacy, from 1871 to 1890, in the next article.

What do you think of the wars Germany had in the 1860s? Let us know below.

References

Doctor Henry Kissinger, Diplomacy (Simon & Schuster Paperbacks 1994)

Doctor Henry Kissinger, A World Restored (Phoenix Press 1957)

H. A. L. Fisher, A History of Europe (The Fontana Library 1972)

Nicola Barber and Andy Langley, British History Encyclopaedia (Parragon Books 1999)

A. W. Palmer, A Dictionary of Modern History, 1789-1945 (Penguin Books 1964)

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography