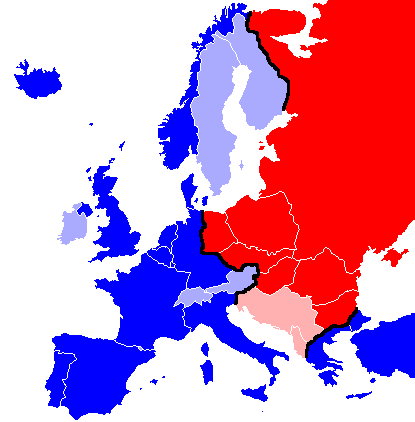

Taiwan’s entry into the global economy was facilitated by a

relationship between the Nationalist military and the US.

Taiwan focused on direct

exports, subcontracting, consignment work for foreign corporations, and joint

ventures. These opportunities provided substantial employment opportunity in

Taiwan where, by the mid-1960s, 150,000 additional jobs were needed each year

to keep pace with population growth.

In 1966, 723 new factories were established in Taiwan by foreign

private corporations, creating 30,000 new job openings annually, 20% of the

annual deficit. Moreover, Taipei’s relatively large number of trained

professional management and technical persons was a factor in attracting

industry.

One corporate executive noted the large reservoir of local

talent stating:

In Taiwan trained people

work at lower levels than anywhere else. There were many trained engineers

among the refugees from the mainland who were working as porters.

Most of the trained refugees had settled in Taipei.

Consequently, few Americans were assigned as resident managers in Taipei and

most jobs went to local residents, not American expatriates.

An in-depth look at the electronics industry will expand our

understanding of the penetration of the local economy by the multinational firm

and the associated impact on Taipei’s urban development.

The Electronics Industry

By 1968 the electrical and electronic goods industry was

Taiwan’s second biggest exporter after textiles and by 1984 it overtook

textiles. The two industries were quite different.

Unlike textiles, the electronics industry had no base in Taipei

prior to the arrival of the multinational corporation in the 1960s. It was

shaped by global forces from the very beginning. Most of its production was

exported, chiefly to the United States. The industry was characterized by a few

foreign-invested assemblers, most from the US, and many locally and privately

owned suppliers of components to them. Thus, the industry was strongly

associated with the emergence of SME’s (small and medium enterprises), which

eventually became the core of Taipei’s export sector.

As previously mentioned, the electronics sector was targeted as

desirable by the military which was deeply involved in efforts to solicit

foreign investment, along with the assistance and advice of US AID. Their hard

work brought in first General Instruments (1964) and then other companies which

set up bonded export factories throughout the island.

Much of the US incentive came from a need to compete with the

Japanese.

In 1953, a Taiwanese firm (Tatung) had signed the first ever

technology agreement between a Taiwanese and a Japanese firm. The Japanese

company agreed to take engineers from the Taiwan firm for training. The

agreement was supported and even funded by US AID (formerly the Economic

Cooperation Administration).

By the late 1950s, a number of Japanese firms began seeking

local partners for electrical assembly in order to obtain lower labor costs.

Seven joint ventures were formed by 1963.

In the next two years, 24 US firms entered into production

agreements with the Taiwanese. In 1965, the first export-processing zone opened

in Kaoshiung in the south of Taiwan. The bonded factories established by many

US firms offered basically the same advantages — relatively unfettered

conditions in return for exporting all of their production. The object was to

cut costs by getting the labor-intensive part of semi-conductor manufacturing —

connecting the wire leads and packaging — done more cheaply than was possible

at home.

By 1966, the Taiwanese government had decided to make Taiwan

into an “electronics industry center.’

A Working Group for Planning and Development of the Electronics

Industry was established to assist in marketing, coordinating production with

the demands of foreign buyers, procuring raw materials, training personnel,

improving quality, and speeding up bureaucratic approval procedures.

In 1967 and 1968, major exhibitions were held to introduce local

manufacturers and foreign investors to each other. The objective was to take

what began in Taiwan as an enclave industry and use it to create an entirely

new sector of parts and components makers and, eventually, assemblers of

finished goods able to compete internationally. According to Thomas B. Gold:

The state was the

contrapuntal partner to the market system, helping to insure that resources

went into industries important for future growth and military strength —

including import substitutes for use in export production, such as synthetic

fibers and plastics, and new export sectors such as electronics. Multinational

companies became important players in these developments, but only after the

state had a well-established presence and leadership position from which it

could channel their activities rather than be made subordinate to global

profits.

The consumer electronics industry is a good example of a dynamic

industry that the state helped initiate and guide, but otherwise did not invest

in directly or tie to state enterprises. Transnational corporations (TNCs)

performed this function. This is a significant departure from the state-led

pattern of the 1950s and represents a clear commitment to the American promoted

approach of granting increased scope for private capital, local and foreign.

In a related move, in 1965, the regime established a publicly

owned China Data Processing Center to push the use of computers in local

industry. In advanced electronics, public research organizations and public

enterprise spinoffs were used to acquire and commercialize new technology, a

strategy promoted by both the Taiwanese military and the US.

Taipei’s locally owned SMEs play an important role.

Electrical and electronics exports grew at a rate of 58% a year

between 1966 and 1971. Foreign firms were quite important in this area.

By the 1970s, over half of foreign firms’ exports were in

electronics and electrical appliances, with foreign firms accounting for 2/3 or

more of total exports from this industry. It is important to note, though, that

foreign-owned companies (companies where more than of the 50% equity is held by

foreigners) were surprisingly small and in no way dominated the economy. In

fact, they paved the way for a new cohort of entrepreneurs, mostly Taiwanese of

a petit bourgeois background.

To underscore, despite the contribution of the American

multinational enterprise to the birth and success of export oriented industry

in Taiwan, it is important to emphasize the significance of Taipei’s locally

owned SMEs. They were an integral part of the drive toward expanded export

capability, becoming more crucial over the course of the 1960s.

SMEs were the essence of the new middle class in Taipei which

was to become a strong force in the move toward a democratization of politics

in a city where the scale of business had a large influence on party

affiliation and competition.

Most of the leaders of Taipei’s largest conglomerates had strong

ties with the KMT, while heads of small and medium sized businesses tended to

support the opposition. This is also consistent with splits along ethnic lines,

for owners of SMEs tended to be native Taiwanese rather than mainlanders.

By Lisa Reynolds Wolfe

Want to find out more about Cold War Taiwan? Well click

here to the see the original article on Lisa’s Cold War Studies site and

scroll down the page for a variety of other great Taiwan articles!

And there is even more on Taiwan by clicking

here. In this article we look at the deadly Taiwan Straits Crisis.