Russia had followed a different path to much of Western Europe for centuries. However, in the 1690s, Tsar Peter I of Russia wanted to learn more about the region and its navies. This led him to mount the Grand Embassy to Western Europe, in particular England. While there he would learn a lot – and one day that learning would help bring him to greatness. Brenden Woldman explains.

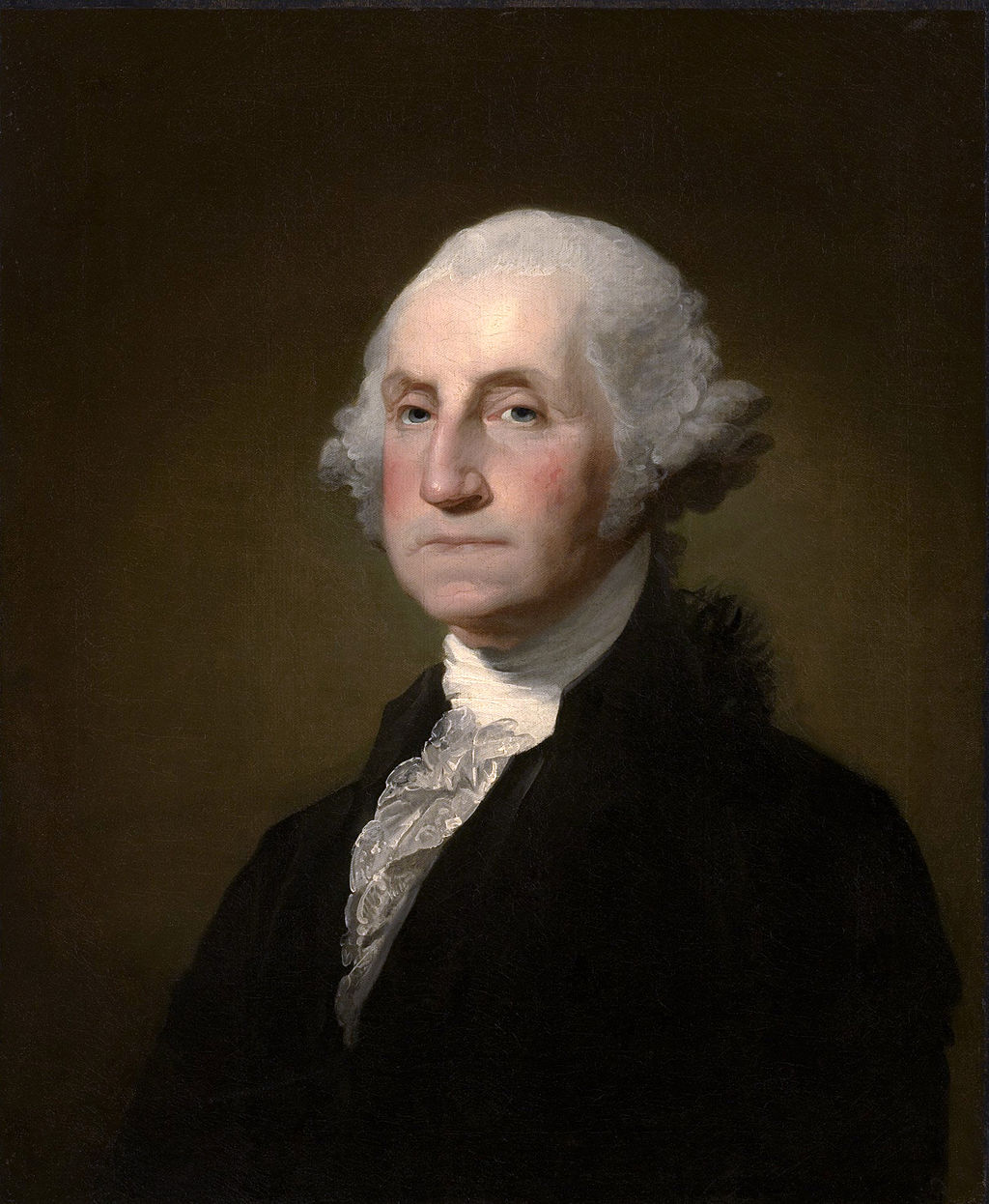

Peter the Great in Holland during the Grand Embassy. Mstislav Dobuzhinsky, 1910.

Like many young Russian students, twenty-five year old Peter Mikhailov left the confines of his homeland in 1697 to “both learn and experience” the culture and technological advances of Western Europe.[1] However, Peter’s joining of “The Grand Embassy” was one of intrigue and mystery for one major reason. “Peter Mikhailov” was nothing more than the alias of Russian Tsar Peter I. Peter, a man who appreciated the European ethos, wanted this incognito trip to bring back not only practical knowledge of Western Europe but also obtain ideas to turn Russia into a modern European nation.

The undercover aspect of his trip was quickly exposed, as the young Tsar was famously one of the tallest men in Europe, standing around six feet, ten inches. The physical reputation of Peter coincided with his social reputation, as Peter, who was known as a rambunctious “merrymaker”, left any place he visited in good spirits through a copious amount of alcohol consumption and partying. Nevertheless, the majority of the European populace did not notice that the leader of the Russian Empire was walking the streets of Europe as a commoner. These adventures led Peter to the Dutch Republic where he learned the art of merchantry and classical ship building while his ventures in Sweden led to the hiring of naval personnel and the sending of ambassadors to Russia.[2] Though the Grand Embassy was considered a success, one of the most important relationships was forged 10 years prior in 1687, when Russian ambassadors were treated coldly by the French government during a treaty signing.[3] After this treatment, Peter had a personal vendetta against the French, which led to an unlikely but resilient bond between Tsar Peter I of Russia and King William III of England.

Peter in England

William of Orange, the King of England since 1688 and the Dutch stadtholder, was a lifelong cynic toward the French. Once hearing of Peter’s hatred of the French (and his want to reopen economic relations with the Russians), the Prince of Orange was overjoyed to allow Peter to sail from the Dutch Republic and across the English Channel. With this most welcome invitation, Peter set sail and landed in England on January 10, 1698.

Peter’s love of Western culture only advanced during his time in England. His admiration of both England and the West was nothing new, as the young Tsar would send the sons of Russian noblemen to acquire a European education.[4] Peter was no different. During his time in England, Peter was given private tours of English historical and economic sites such as the Royal Society and the Tower of London to view the Royal Mint.[5] The young Tsar also viewed the English military Arsenal, as well as learning about English culture through artistic excursions in places such as Oxford, London, and Windsor.[6] In the realm of science, Peter visited the Royal Observatory at Greenwich due to his interest in using the stars for navigation.[7] However, Peter was shocked with the social and economic relations throughout England.

For the Tsar, England was home of a flourishing merchantry, a free press, an open government, and a cosmopolitan ambiance, which were all things Peter wanted to strive for in his own empire.[8] Hearing open debate among the people upon his visit to the English Parliament left the Tsar feeling elated, stating, “It is good to hear subjects speaking truthfully and openly to their King. This is what we must learn from the English”.[9] Yet, with all of the Tsar’s interests in Westernization, it was in fact one particular aspect of English culture that brought Peter there: the Royal Navy.

Learning about the Royal Navy

Peter left Holland having learned much about the art of shipbuilding but believed that the Dutch had no original theories about naval construction, unlike the English.[10] The young Tsar’s obsession with shipbuilding stemmed from the simple fact that Russia established a national navy in 1696, only two years prior. Needless to say, Peter needed advice on how to build a navy. King William III sent and subsequently gave Peter the Royal Transport, a ship used to carry prestigious guests from Holland to England and one of the most modern ships in the world.[11] This gift became a key example for Russian engineers to build up-to-date ships.

When Peter arrived in England, he moved into writer John Evelyn’s home in Deptford, south-east of London. The reason for Peter moving to a small house in Deptford was that it was close to the dockyards of King’s Wharf, where Peter regularly visited and studied the ships that were being built.[12] Moreover, the Tsar would repeatedly sketch the ships at the Deptford dockyards whilst also studying the “blueprints” of English naval architecture. However, the Russian Emperor did not spend his entire time studying English ships at King’s Wharf. To hone in on naval tactics for military conflict, Peter traveled to Portsmouth.

At Portsmouth, Peter reviewed the English warships, diligently noting the number and caliber of the guns on the ships while also studying mock naval battles tactics, logistics, and strategies, all of which the English specially arranged for the young Tsar just off the Isle of Wight.[13] With the new information about Western culture, naval architecture, and tactics learned in England, Tsar Peter I would return back to Russia and implement them in an attempt to make Russia a modern, European country.

What did Peter the Great take back to Russia?

Peter’s time in England came to an end on April 22, 1698. The immediate reaction by the English government of Peter after he left was one that supported the Russian stereotypes of the time. For the English, Peter was unintelligent, backwards, and frequently drunk. Even on his travels Peter’s party lifestyle could not subside, as he would regularly write about how he “stayed at home and made merry” to such a magnitude that John Evelyn made the British government pay compensation for three hundred and fifty pounds to cover the damage made by Peter’s “merrymaking”.[14] However, though the English may have thought Peter had learned nothing, the Tsar took his newfound knowledge and advanced Russia in profound ways.

The open policies and social relations between the government and the people in England highly influenced Peter in his later years when he implemented his highly influential Table of Ranks. Furthermore, English and Western culture helped shape the young Russian nobility for generations to come - throughout the eighteenth century and beyond. However, the knowledge of shipbuilding that Peter brought back to Russia helped change the country. When Peter returned to Russia, the Tsar established a large shipbuilding program in the Baltic Sea which, by his death in 1725, had 28,000 men enlisted in a Navy of nearly 50 large ships and over 800 smaller vessels.[15] It is also important to note that in Peter’s greatest fight, the Great Northern War against Sweden, the newly established Russian Navy was a key component to the Russian victory in the war. For Peter, the Grand Embassy and his travels in England were more than a mere adventure for a young ruler. They were instrumental in making Peter I into Peter the Great.

What do you think of the article? How important was Peter the Great’s time in England for his later successes? Let us know below.

[1] V. O. Kli︠u︡chevskiĭ, Peter the Great (Boston: Beacon Press, 1984), 24.

[2] Lindsey A. J. Hughes, Russia in the age of Peter the Great (Hew Haven Conn.: Yale University Press, 2000), 23-24.

[3] Hughes, Russia in the age of Peter the Great, 25.

[4] Kli︠u︡chevskiĭ, Peter the Great, 29.

[5] "Peter the Great," Royal Museums Greenwich | UNESCO World Heritage Site In London, July 21, 2016, http://www.rmg.co.uk/discover/explore/peter-great.

[6] Hughes, Russia in the age of Peter the Great, 25.

[7] "Peter the Great," Royal Museums Greenwich | UNESCO World Heritage Site In London, July 21, 2016, http://www.rmg.co.uk/discover/explore/peter-great.

[8] Hughes, Russia in the age of Peter the Great, 23.

[9] Kli︠u︡chevskiĭ, Peter the Great, 28.

[10] Ibid., 29.

[11] "Peter the Great," Royal Museums Greenwich | UNESCO World Heritage Site In London, July 21, 2016, http://www.rmg.co.uk/discover/explore/peter-great.

[12] Ibid.,

[13] Kli︠u︡chevskiĭ, Peter the Great, 28.

[14] Ibid., 29.

[15] "Peter the Great," Royal Museums Greenwich | UNESCO World Heritage Site In London, July 21, 2016, http://www.rmg.co.uk/discover/explore/peter-great.