Consequences of Second Manassas

The Confederate victory at Second Manassas August 28-30, 1862 followed victories in The Valley Campaign and the Peninsula. The casualties incurred by the Army of the Potomac included 14,000 killed or wounded of 62,000 engaged, compared to about half of that for the Army of Northern Virginia. Then on September 1, Stonewall Jackson defeated a Union cohort retreating from the battlefield, resulting in the deaths of 2 iconic Union generals. The Battle of Chantilly further supported the notion that the Confederate was invincible.

General Pope was relieved of command and sent to Minnesota, never to be heard from again. A subordinate would state about Pope, “I dare not trust myself to speak of this commander [Pope] as I feel and believe. Suffice to say ... that more insolence, superciliousness, ignorance, and pretentiousness were never combined in one man.” Pope would blame Fitz-John Porter for the loss, even though that wasn’t the case; Porter would be heard from again at Antietam but his career would be destroyed soon after.

It would be hard to imagine what President Lincoln was going through at that moment. After a year plus of fighting, none of his generals had ever defeated the Rebels in the eastern theater, although General Halleck had done well enough in the west, thanks in large part to a crazy general named Sherman and a drunken one named Grant. The backbiting in the army was at full swing, the blockade was having only a moderate effect, and his diplomat to Britain, Charles Francis Adams, was afraid that PM Gladstone would force negotiations to end the conflict. The soldiers who had been enlisted for one year were now done unless they wanted to re-enlist. Casualties were high and there was a pervasive sense of incompetence at the top of the military leadership.

And even worse, General Lee was rumored to have crossed the Potomac on September 3rd. The United States was being invaded, the Union army had no commander, and the national mid-term elections were coming up in 2 months. President Lincoln had a serious crisis on his hands, perhaps the most serious threat to the United States in our history.

General George McClellan

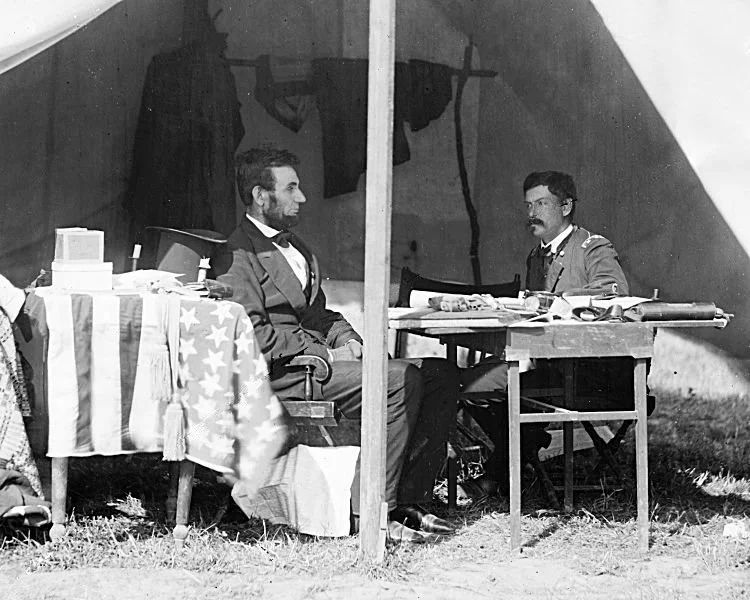

Following the Peninsula Campaign, Lincoln had fired McClellan for his incompetence as a general and his arrogant attitude. But now, 6 months later, Lincoln grudgingly called McClellan back into action in defense of Washington. Lincoln felt compelled to take this step because McClellan had the confidence of the soldiers. In the early stages of his command, McClellan was able to build up the Union army into a more powerful unit than the Confederacy had faced at Bull Run. He was really a brilliant administrator and he had amassed a well trained and supplied army, had planned a clever strategy to take Richmond, and his army greatly admired him. Despite these organizational successes, his apparent slowness, almost an unwillingness, to fight a battle slowed the war beyond what Lincoln could politically accept.

His repeated unforced retreats in the Peninsula led to a lack of confidence. But now, Lincoln needed a general to meet an imminent threat and he went back to McClellan. McClellan was very popular among the soldiers and the military. The parallels are really very interesting with the one at the onset of the Gettysburg campaign, when Hooker was dismissed on the eve of battle during an invasion after a large loss in Virginia.

It is believed that McClellan purposely withheld his men from helping Pope at Second Manassas. In late August, two full corps of the Army of the Potomac had arrived in Alexandria, but McClellan would not allow them to advance to Manassas because of what he considered inadequate artillery, cavalry, and transportation support. He was accused by his political opponents of deliberately undermining Pope's position. But he is especially criticized by historians for his letter to his wife on August 10, "Pope will be badly thrashed within two days & ... they will be very glad to turn over the redemption of their affairs to me. I won't undertake it unless I have full & entire control." He told Abraham Lincoln on August 29 that it might be wise "to leave Pope to get out of his scrape, and at once use all our means to make the capital perfectly safe.”

After his severe defeat, Pope was relieved of command, McClellan reinstated. Lee’s invasion of Maryland and the Battle of Antietam occurred just 3 weeks later.

General Lee

After Second Manassas, General Lee enjoyed widespread popular acclaim and the confidence of the president and his cabinet. He had turned every battle into a victory, defeating two union commanders in just a few months. While supplies and armaments were in short supply, at this stage they seemed adequate. It was a propitious moment to plan an invasion of the north. But with autumn coming, and the events it would bring, Lee had to move quickly and efficiently.

He had two excellent Corps Commanders in Longstreet and Jackson. His division commanders were also terrific, but their spirit was high, and their personalities clashed with their superiors. Still, success tends to dampen such disagreements.

Lee had these objectives with an invasion of the North:

To move the focus of fighting away from the South and into Federal territory.

Recruit in western Maryland and bring secession leaning citizens hope

Achieve a military victory in the north,

Perhaps could lead to the capture of the Federal capital in Washington, D.C.

Confederate success could also influence impending Congressional elections in the North and

Persuade European nations to recognize the Confederate States of America.

This was the single moment in the war that Lee was truly in the ascendancy. Unlike the Gettysburg campaign 9 months later, which was a desperate move, this invasion made military and political sense. This likely was the real high water mark of the confederacy. Clearly Lee recognized that Stonewall Jackson thrived on independent action especially attack situations, and placed him in that position at Harpers Ferry. He also saw Longstreet as embodying the main army, as an attacking defender, and used him for that purpose in the campaign.

The Campaign Begins

Lee started off September 3 and crossed the Potomac at two fords west of Washington. His army moved to Frederick, camping in a field 2 miles south of the town at Best’s Farm.

The idea for the invasion was well conceived. Although many modern day civil war enthusiasts consider this a terrible idea and suggest that the Confederacy should have stayed on defense, not fritter away their resources. Lee actually had a bold plan that few civil war buffs know about, in large part because it didn’t work. Lee's invasion of Maryland was intended to run simultaneously with an invasion of Kentucky by the armies of Braxton Bragg and Edmund Kirby Smith. Lee is typically criticized as lacking that kind of vision in coordinating attacks, as Grant for example had. But this is the case that proves that criticism wrong.

Fredrick, Maryland is centrally placed between Washington and Baltimore. The B& O RR set up a supply line to that town. It is also well located to Harper’s Ferry. And, it was the new capital of Maryland when it removed from Baltimore. It today is a very cute small town; the National Medical Civil War Museum is located there. This was appropriate, as the town was overfilled with the wounded after Antietam.

In September 1862, Confederate forces crossed the Potomac River at several places. Here are the main crossing points utilized by Lee's army prior to the Battle of Antietam:

White's Ford: Located near Leesburg, Virginia, White's Ford was the major crossing point used by Lee's army as they entered Maryland (see drawing). They crossed the Potomac River here on September 4-6, 1862, and began their advance into Union territory.

Cheek’s Ford: Upstream of White’s Ford, also was used by Confederate forces

Noland's Ferry: Situated downstream from White's Ford, Noland's Ferry was another crossing point used by Lee's forces. They crossed the Potomac here on September 7-8, 1862, continuing their movement into Maryland.

Lee wanted to use Leesburg as his stepping off point to get to Frederick. The turnpike leading out of Snickers Gap goes to Leesburg, This turnpike was an old Indian trail that white settlers had widened and had become the main thoroughfare between the Shenandoah and Loudon County. Up to this point, Lee was using main roads for supply lines, which was clever strategically, as there were no railroads except as connected to Harper’s Ferry.

Lee was moving to attack Harpers Ferry, which is west of Frederick. He was not moving to advance on the big eastern cities. It is a fable that General Lee’s invasions had major cities as targets. His supply lines were too tenuous to try: he couldn’t have held them, in any case.

Harpers Ferry was a critical strategic point early in the war. It was the north-south crossroads from the Shenandoah Valley to Western Maryland, and the joining of the Potomac and Shenandoah Rivers. It contained a large arsenal and was a concentration for military manufacturers. All of these factors played key roles in why it was a crucial military goal. In fact, control of the town changed 8 times during the war, remaining in Union control for most of it.

Surrounded on three sides by steep heights, the terrain surrounding the town made it nearly impossible to defend; all one had to do with take the heights and shell the town until it surrendered. Stonewall Jackson once said he would rather “take the place 40 times than undertake to defend it once.”

The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad and the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal were crucial supply lines connecting the east with the west, and they ran right through town. These assets were the real reasons why Harpers Ferry was so strategically important. If you take Harpers Ferry the RR is cut in half and the east can’t get supplies to the west without a large detour. And most importantly, Lee could then use this town as his supply depot for further operations deeper into Maryland. In the Gettysburg campaign, Lee skipped this step and instead went further west, in order not to have to hold territory. This decision helped him speed up on the way to Gettysburg, but could have led to disaster on the retreat.

McClellan Takes Command

General McClellan assumed command of an army that was truly leaderless. When McClellan took charge of the Union forces on Sept. 1, he inherited four separate armies, thousands of untrained recruits and numerous other small commands that needed to be made ready in a hurry. To further complicate matters, three of his senior commanders had been ordered relieved of duty, charged with insubordination against Pope.

McClellan knew that Lee was in his northwest and moved, supposedly slowly, to that region. By the time he arrived in Frederick on September 13, Lee had been gone for 4 days. Classic histories portray McClellan's army as moving lethargically, averaging only 6 miles a day.

McClellan commanded in theory 28 cavalry regiments. But the disastrous Manassas campaign had worn out the horses of almost half the Union regiments, while most of the remainder were stranded at Hampton Roads by gale-force winds. For the first week of the campaign, McClellan could only count on perhaps 1,500 cavalry from two regiments and a few scattered squadrons from his old army to challenge some 5,000 Confederate cavalry soldiers screening Lee’s army.

In the week it took for Lee's army to march to Frederick, McClellan's army traveled an equal distance to redeploy on the north side of Washington. This was accomplished as he reshuffled commands, had his officers under charges reinstated and prepared to fill out his army with untrained recruits. Although he is rightly criticized for having “the slows”, criticisms of his aggressiveness in this campaign have not held up to in depth scholarship.

Special Order #191

Lee and the Confederate Army bivouacked on the Best Farm, about 2 miles south of Frederick, near the Monocacy River. This site would 2 years later be the location of the Battle of Monocacy but on September 9, 1862, the Union army was nowhere around. On the farm field showed in the photo, General Lee set up headquarters and had orders written that laid out the campaign plans for the next couple of weeks. Special Order #191 was written here, and couriers were directed to bring copies to the corps and crucial division leaders.

In Special Order #191, General Lee outlined the routes to be taken and the timing for the attack of Harpers Ferry. It provided specific details of the movements his army would take during the invasion of Maryland.

*****************************************************************************

“Special Orders, No. 191

Hdqrs. Army of Northern Virginia

September 9, 1862

The citizens of Fredericktown being unwilling while overrun by members of this army, to open their stores, to give them confidence, and to secure to officers and men purchasing supplies for benefit of this command, all officers and men of this army are strictly prohibited from visiting Fredericktown except on business, in which cases they will bear evidence of this in writing from division commanders. The provost marshal in Fredericktown will see that his guard rigidly enforces this order.

Major Taylor will proceed to Leesburg, Virginia, and arrange for transportation of the sick and those unable to walk to Winchester, securing the transportation of the country for this purpose. The route between this and Culpepper Court-House east of the mountains being unsafe, will no longer be traveled. Those on the way to this army already across the river will move up promptly; all others will proceed to Winchester collectively and under command of officers, at which point, being the general depot of this army, its movements will be known and instructions given by commanding officer regulating further movements.

The army will resume its march tomorrow, taking the Hagerstown road. General Jackson's command will form the advance, and, after passing Middletown, with such portion as he may select, take the route toward Sharpsburg, cross the Potomac at the most convenient point, and by Friday morning take possession of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, capture such of them as may be at Martinsburg, and intercept such as may attempt to escape from Harpers Ferry.

General Longstreet's command will pursue the same road as far as Boonsborough, where it will halt, with reserve, supply, and baggage trains of the army.

General McLaws, with his own division and that of General R. H. Anderson, will follow General Longstreet. On reaching Middletown will take the route to Harpers Ferry, and by Friday morning possess himself of the Maryland Heights and endeavor to capture the enemy at Harpers Ferry and vicinity.

General Walker, with his division, after accomplishing the object in which he is now engaged, will cross the Potomac at Cheek's Ford, ascend its right bank to Lovettsville, take possession of Loudoun Heights, if practicable, by Friday morning, Key's Ford on his left, and the road between the end of the mountain and the Potomac on his right. He will, as far as practicable, cooperate with General McLaws and Jackson, and intercept retreat of the enemy.

General D. H. Hill's division will form the rear guard of the army, pursuing the road taken by the main body. The reserve artillery, ordnance, and supply trains, &c., will precede General Hill.

General Stuart will detach a squadron of cavalry to accompany the commands of Generals Longstreet, Jackson, and McLaws, and, with the main body of the cavalry, will cover the route of the army, bringing up all stragglers that may have been left behind.

The commands of Generals Jackson, McLaws, and Walker, after accomplishing the objects for which they have been detached, will join the main body of the army at Boonsborough or Hagerstown.

Each regiment on the march will habitually carry its axes in the regimental ordnance—wagons, for use of the men at their encampments, to procure wood &c.

By command of General R. E. Lee

R.H. Chilton, Assistant Adjutant General”

*****************************************************************************

Lieutenant General Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson was to lead the advance and capture Harper’s Ferry. DH Hill was designated to guard the rear. General Longstreet was to encircle the towns and roads leading to Harpers Ferry. Jackson was to take Harpers Ferry while the rest of Lee's army was posted at Boonsboro under command of Maj. Gen. James Longstreet. Lee hoped that after taking Harper's Ferry to secure his rear, he could carry out an invasion of the Union, wrecking the Monocacy aqueduct, before turning his attention to Baltimore, Philadelphia, or Washington, D.C. itself. Unlike the Pennsylvania Campaign, Lee had a real plan. Lee did not expect to be attacked by McClellan at this vulnerable moment. He was hiding at Boonsboro precisely to keep McClellan guessing. He could not know that McClellan knew where he was.

The places where parts of the army were sent controlled the roads into and out of Harpers Ferry. Martinsburg holds the road across from Whites Ford. Boonsboro hold the road north of Harpers Ferry. Once Lee’s various divisions were in place, Harpers Ferry was in essence surrounded.

Lieutenant Colonel Robert H. Chilton, Lee’s assistant adjutant general (chief of staff), wrote out 8 copies of the order, 1 to each of the generals named and 1 to President Davis. At the time that Special Order #191 was written, Hill was under the command of Jackson, his brother-in-law. Jackson personally copied the document for Hill, because once the army crossed into Maryland, the order specified that Hill was to exercise independent command as the rear guard. For this reason, Jackson copied and sent Hill the order because he didn’t know if Chilton had done so. But, since Special Order #191 conveyed Hill’s having an independent command once entering Maryland, Chilton had in fact sent Hill a copy. DH Hill received only the letter from General Jackson, and never received the copy written by Chilton. Since he had received his orders, no one was concerned that a copy had been lost.

Famously, the order was lost, and was found 4 days later by men under General Alpheus Williams.

https://emergingcivilwar.com/2022/02/24/who-lost-the-lost-order/

and later found by the Union army about a half mile north and east of this location.

https://www.rebellionresearch.com/special-order-191-ruse-of-war-part-1

https://www.theodysseyonline.com/the-insignificance-of-special-order-191

When General McClellan came into the possession of Special Order #191, he had an accurate and timely picture of exactly where the components of the Confederate army were located and what routes they were going to be using in the next several days. He knew that the Confederate army was divided and he knew exactly where they were. Lee had dangerously split his army into five parts. Three columns had converged on Harpers Ferry to capture the Federal garrison there, a fourth column was in Hagerstown, and a fifth column was acting as a rear guard near Boonesboro, Md.

Most traditional histories of the Antietam Campaign assert that McClellan was given Gen. Robert E. Lee's plans in Frederick, Md. at noon, Sept. 13. The narrative states that he waited 18 hours before acting on the find. By waiting before taking advantage of this intelligence and reposition his forces, he squandered the best opportunity in the war to defeat Lee conclusively.

These criticisms stem from the belief that McClellan moved too slowly and cautiously to attack Lee. They assert that when a copy of Lee’s plans fell into McClellan’s hands, the Union general wasted precious hours before advancing. Politicians from the 1860s onward and countless historians have claimed he could have easily destroyed Lee’s army during the campaign and ended the war in 1862, sparing the country another two and a half years of bloody conflict.

A more recent re-evaluation disputes this sequence of events entirely, citing long overlooked evidence that McClellan moved quickly and there was no 18-hour delay. Some historians believe that for this reason, the loss of the Special Order #191 wasn’t as decisive as history makes it out to be. That it had in fact little impact on subsequent events. Gene Thorp in a 2012 article in The Washington Post cited evidence that the vanguard of Army of the Potomac was in motion all day on the 13th due to orders McClellan issued. After the war, McClellan held to the claim that he acted immediately to put his armies on the move.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/style/in-defense-of-mcclellan-at-antietam-a-contrarian-view/2012/09/06/79a0e5cc-f131-11e1-892d-bc92fee603a7_story.html

Early in the morning of Sept. 13, most of the Union army was on the move to Frederick, Md. including McClellan, who was relocating his headquarters there from Urbana. At the conclusion of the march, a copy of Lee’s orders was found in an open field. What time this "Lost Order" was found, and when McClellan received it, has been relatively unchallenged until recently.

In "Landscape Turned Red," Stephen Sears asserts that McClellan verified before noon that the papers were legitimate, then exhibited his usual excessive caution and failed to move his army for 18 hours. To back up this theory, Sears cites a telegram that McClellan sent to Abraham Lincoln at "12 M" — which Sears says stands for meridian or noon — in which McClellan confidently informs the president that he has the plans of the enemy and that "no time shall be lost" in attacking Lee. In summary, the traditional view is:

McClellan had the Lost Order by noon as is proven by the telegram from him to Lincoln that is dated "12M" for Meridian.

McClellan waited 18 hours before moving his troops after finding the Lost Orders

The original telegram received by War Department is clearly dated "12 Midnight". After the book's publication, though, the original telegram receipt was discovered by researcher Maurice D'Aoust in the Lincoln papers at the Library of Congress. It shows that the telegram was sent at midnight (the word was written out) — a full 12 hours later than Sears thought. D'Aoust points this out in the October 2012 issue of Civil War Times in an article entitled " 'Little Mac' Did Not Dawdle."

In the disputed telegraph, McClellan wrote Lincoln, "We have possession of Catoctin [Mountain]," which is important because those two passes were still held by the Confederates at noon. The Braddock Pass was not gained until 1 p.m. and the Jefferson Pass further south was not taken until near sunset. This is evidence that there was no noon message.

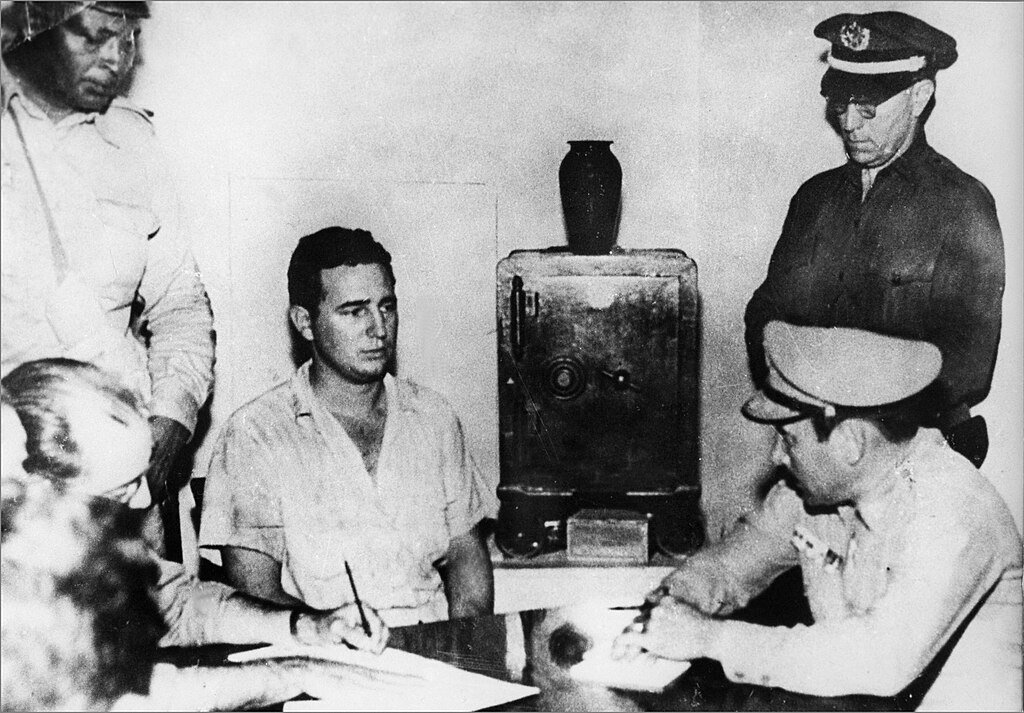

McClellan is known to have been riding through the town of Frederick at the 11 am hour (see photo), to raucous crowds, thrilled to see him. Its hard to square this with being told of the orders and telling President Lincoln about it less than an hour later.

The Lost Order was not found until after the 12th Corps, of which the 27th Indiana Regiment belonged, ended its morning march. At least five accounts show that the Corps completed its march about noon, which would make it impossible for McClellan to have written and sent a telegraph that contained information about the Lost Order at the same time it was found. The commander of the unit that found the order notes that it was found after its march ended at noon and that it was carried to army staff soon thereafter.

McClellan issued orders at 3 p.m. for his cavalry chief to verify that the Lost Order was not a trick. It seems out of character for someone who is normally considered so cautious to confidently inform Lincoln of the find three hours before he tried to confirm the accuracy of its contents. From this, we can deduce that McClellan had the orders at 3 pm or sooner but after noon.

The Signal Corps reported that "in the evening" it transmitted a message from Lincoln to McClellan, and a return message from McClellan to Lincoln. The report mentions no other transmittal of information between the two men at any other time of the day.

McClellan had the vanguard of the army, Burnside's 9th Corps, on the move at 3:30 p.m. These men filled the road west to Lee's rear guard at South Mountain well into the night. Near sundown, at 6:20 p.m., he began to issue orders for the rest of his army to move, with most units instructed to be marching at sunrise. (They were roused from sleep at 3 a.m.) In the midst of this activity, at midnight, the general telegraphed the president to tell him what was going on.

By 9 a.m. on Sept. 14, the first troops had climbed South Mountain and met the Confederate rear-guard in battle. By nightfall, McClellan's army carried the heights and forced a defeated Lee to find a new defensive position along Antietam Creek. McClellan pursued the next morning and within 48 hours initiated the Battle of Antietam, which forced Lee back across the Potomac River. This seems like a pretty expeditious sequence of events, not a delay.

Additionally, a detachment of the 9th Corps in conjunction with cavalry marched from Frederick and took the southern Catoctin pass at Jefferson before sunset.

The 6th Corps, about 12,000 men, marched from Buckeystown to the gap in the Catoctin at Jeffersonville, from the evening until at least 10 p.m. A night march beyond that point would have been risky since it was not known precisely where the Confederates were in the valley beyond.

The 1st Corps, about 10,000 men, marched to Frederick the evening of Sept. 13 to be ready for an advance on the Confederate rear-guard the following morning.

Harpers Ferry

There were two significant engagements in the Maryland campaign prior to the battle of Antietam. Both directly impacted the major battle to come. Maj. Gen. Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson's captured Harpers Ferry on September 12. This is important because Jackson’s Corps, a large portion of Lee's army, was absent from the Battle of South Mountain and the start of the battle of Antietam, attending to the surrender of the Union garrison. To understand Antietam, the dates and times are almost as important as they are at Gettysburg.

The Battle of Harpers Ferry took place over 4 days. Stonewall Jackson found Maryland Heights stoutly defended but brigades led by Barksdale and Kershaw attacked strongly, with retreat of the Union troops across the Potomac the next day. On September 14, the rest of his infantry arrived and found Loudon Heights undefended. Jackson placed his artillery on these heights while his infantry confronted the Union army on Maryland Heights. An attack on the Union left flank was threatened by AP Hill while 50 guns began a bombardment. The Union commander realized the situation was hopeless and surrendered.

Colonel Dixon Miles was the union commander at Harpers Ferry. At age 58 he was the oldest active colonel in the Union army; a West Point graduate, he led a division at First Manassas but was held in reserve on account that he was drunk. A court of inquiry confirmed this, but he was given command of Harpers Ferry instead of a court martial. Maj Gen John Wool gave miles orders on September 5: "you will not abandon Harpers Ferry without defending it to the last extremity." Wool sent another saying "there must be no abandoning of a post, and shoot the first man that thinks of it". The Union leadership appreciated the likelihood that the town would be attacked. Why they sent no more men to defend it isn’t clear, Why Miles kept his men in the town and not positioned on the heights isn’t comprehensible. Miles was mortally wounded in the artillery barrage.

AP Hill was with Jackson at Harpers Ferry following his feud and threatened duel with General Longstreet after newspaper articles concerning the Battle of Glendale, Hill was transferred to Jackson’s command. He had performed magnificently at Second Manassas. But he clashed with Jackson during the march in Maryland, who had Hill arrested and charged him with eight counts of dereliction of duty after the campaign. For this reason, Jackson left him behind when Harper’s Ferry was captured to process the POWs.

The delay in taking Harpers Ferry had direct consequences on the Battle of Antietam. Jackson has been criticized for taking so long. It’s hard to see how things could have been done any faster. Had Miles positioned his troops with more thought, it would have taken even longer. Had Lee considered this in his placement of the troops around the town? Its not clear, but its is noteworthy that Lee didn’t try to take Harpers Ferry in the Gettysburg invasion.

The Battle of South Mountain

The implications of this delay were enormous. Recall that Special Order 191 was written September 9 but not retrieved by Union forces until September 13. Even though the intelligence was four days old, McClellan knew that Jackson was behind schedule at Harper’s Ferry, which was surrounded but not yet taken, and that Lee’s army was divided and separated over miles of Maryland countryside. Aware that a portion of Lee’s army was now vulnerable to attack, McClellan advanced toward the South Mountain range to attack Lee’s forces there.

McClellan followed Lee’s army based on the routes identified in Special Order 191. Union forces attempted to break through South Mountain to advance toward Lee's army, which would eventually concentrate near Sharpsburg. McClellan was lucky that Lee’s orders were found, that is for sure; otherwise he would have been searching for Lee all over western Maryland. But having them in his possession, he simply followed the road map Lee had drawn for him. There are 2 roads leading west from Frederick; one goes to the north gaps to Hagerstown and one goes south toward Williamsport. Lee left the southern gap exposed, likely due to limitations on manpower and supplies.

The Battle of South Mountain took place on September 14, 1862. It is very important to re-emphasize, see the timeline in the answer 2 days ago, that the lost orders were given to McClellan on September 13 and a battle occurred the very next day. Lee was surprised that the lethargic McClellan had caught up with him so rapidly. Jackson was just wrapping up Harpers Ferry. He only had Longstreet and DH Hill to defend the passes.

Although the Confederate troops ultimately had to retreat, they put up a strong resistance and delayed the Union's progress, giving Lee valuable time to reposition his forces. While Union forces were able to gain control of the mountain, they could not stop Lee from regrouping. Confederate defenses delayed McClellan's advance enough for Lee to concentrate the remainder of his army at Sharpsburg, setting the stage for the Battle of Antietam three days later.

During the Battle of South Mountain, engagements took place at various passes and gaps within the South Mountain range. The Union forces, commanded by General George B. McClellan, aimed to seize control of the mountain passes and break through the Confederate defensive positions. In the battle, Union army attacked at 3 gaps.

The passes and gaps of South Mountain, particularly Turner's Gap, Fox's Gap, and Crampton's Gap, offered natural defensive positions. Lee was using South Mountain as a screen, but McClellan had pursued faster than was anticipated. With Jackson at Harpers Ferry, Lee fell back along the roads that led mainly to the northern gaps. Lee ordered Longstreet to be in this location to delay the Union advance.

DH Hill was at the northernmost pass with Longstreet because he had been the rear guard and naturally came to these 2 passes. A single 5,000-man Confederate division under D.H. Hill protected Fox’s and Turner’s Gaps at South Mountain. Early on September 14, Union Gen. Jacob D. Cox’s Kanawha Division of the Union IX Corps launched an attack against Samuel Garland’s brigade at Fox’s Gap. Cox’s 3,000 Ohioans overran Garland’s North Carolinians, driving the Southerners from behind a stonewall and mortally wounding Garland. However, by nightfall, Confederate soldiers still held the western edge of Fox’s gap.

At Turner’s Gap, Union Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker’s I Corps arrived on the steep mountainside near Frostown, and divisions under George G. Meade and John P. Hatch made relentless charges on the gap’s northern edge. After a brutal firefight along a cornfield fence, Hatch broke through the Rebel line. Only the timely arrival of reinforcements from Longstreet prevented the Confederate line from collapsing. By nightfall, the Confederates still maintained control of Turner’s Gap.

1. Turner's Gap: This was the northernmost and most heavily defended pass. Confederate forces, under the command of General D.H. Hill, held strong defensive positions on the slopes of Turner's Gap, while Union troops, led by General Joseph Hooker, made determined efforts to dislodge them.

2. Fox's Gap: Located south of Turner's Gap, Fox's Gap saw intense fighting between Confederate forces commanded by General Samuel Garland and Union troops led by General Jesse Reno. The Union forces eventually managed to seize control of this pass.

3. Crampton's Gap: Situated south of Fox's Gap, Crampton's Gap was the southernmost pass where significant fighting occurred. Union troops, led by General William B. Franklin, engaged Confederate defenders commanded by General Howell Cobb. The Union forces successfully captured Crampton's Gap, further pressuring the Confederate positions.

Crampton’s Gap. Civil War enthusiasts typically overlook the Battle of Crampton’s Gap as merely a prelude, but in fact, Antietam happened precisely because of this battle. It was the key to the entire campaign.

McClellan ordered Maj. Gen. William Franklin and his VI Corps to set out for Burkittsville from his camp at Buckeystown 9/14 at daybreak, with instructions to drive through Crampton's Gap and attack McLaws' rear. Although he sent the order immediately, by allowing Franklin to wait until morning to depart, his order resulted in a delay of nearly 11 hours. When the Federals reached Burkittsville around noon, the Confederate artillery opened up. In Burkittsville, while under artillery fire, Franklin assembled his troops into three columns. At 3 p.m., after a delay of nearly 3 hours, the VI Corps finally began its assault. The reason for the delay has never been ascertained, but it would prove costly.

The Confederate force consisted of one battery of artillery, three regiments of infantry under Brig. Gen. William Mahone, one brigade under Brig. Gen. Howell Cobb, and a small cavalry detachment under Col. Thomas T. Munford. After the report of a very large number of camp fires indicating a much larger Union force than anticipated, General Lee recognized the threat this posed to his split forces, so the order was sent down to General Cobb to ..."hold the gap if it cost the life of every man in my command".

Only about one thousand Confederates defended Crampton's Gap, the southernmost of the South Mountain passes. At around 4:00 p.m., Maj. Gen. Henry Slocum's division charged into the gap and dislodged the Confederates from the protection of a stone fence. The arrival of four regiments under Gen. Howell Cobb did little to stem the Union tide. Reinforced by a brigade of Vermonters, the Federals made a second attack and drove the remaining Confederates down the western slope of South Mountain, leaving the VI Corps in possession of Crampton's.

The Union attack broke the makeshift Rebel line but only at 6 pm, too late for a follow up attack. This gave Lee a chance to salvage his force.

Even though the Confederates still held onto Fox’s and Tuner’s Gaps, Lee ordered his outnumbered forces to withdraw from South Mountain. By sunrise on September 15, the Confederates had completely withdrawn. Once the gap is in Union hands, a road connects it to all of the roads behind the mountain, and so Hill and Longstreet can be surrounded. Longstreet and Hill had to retreat that evening.

Once Crampton’s Gap was taken, even though Turner’s and the Confederates held Fox’s Gap at the end of the day they were not defensible any longer. Consequently, Lee retreated.

Aftermath

The Battle of Antietam took place on September 17, 1862, 3 days after the Battle of South Mountain. More Americans died in battle on that day than in any other day in our nation’s history. The battle was a clear Union victory. The consequences were enormous. Great Britain would never become officially involved in the war or recognize the Confederacy. The Republicans won the mid=term elections. Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation in the shadow of victory.

Although McClellan defeated Lee, ending the invasion, he did not pursue the ANV despite Lincoln’s persistent entreaties and orders. McClellan was relieved of duty that October, with Ambrose Burnside taking command. McClellan would run against Lincoln for president in 1864.

What do you think of the Maryland Campaign of 1862? Let us know below.

Now, if you missed it, read Lloyd’s piece on how the Confederacy funded its war effort here.