The Assassination

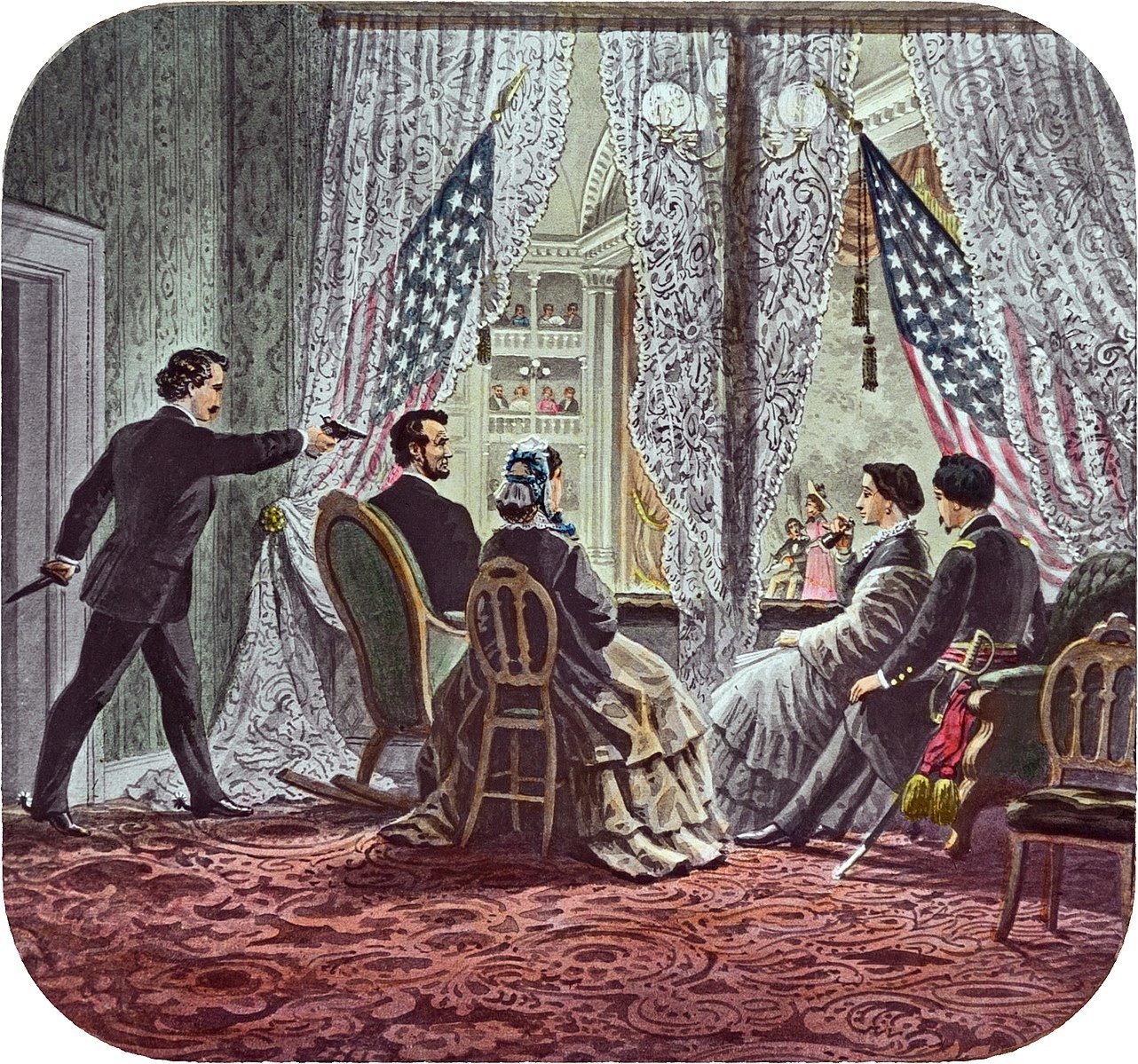

The assassin silently opened the first door to the President’s theater box, fully aware that the bodyguard was not around. He barricaded the door behind him, using a stick that he wedged in between the door and the wall. He then looked through a small peephole he’d previously carved in the second door. The time was shortly after 10 PM. He waited for the particular line in the play he knew was received by the audience with loud laughing and noise, to be spoken by actor Harry Hawk (playing Asa Trenchard). When he heard the line, “Don’t know the manners of good society, eh? Well, I guess I know enough to turn you inside out, old gal; you sockdologizing old man-trap!” and heard the expected audience response, he opened the second door. He silently moved forward and took one shot at the back of the President’s head, who was laughing. He dropped his derringer, then pulled a knife to fight off the officer accompanying Lincoln that night, who had grabbed his coat to restrain him.

Well aware of the layout of Ford’s Theater, having acted there numerous times, his escape route was to jump from the balcony where the box was located to the stage. When he jumped to the stage, Booth broke the fibula, the small bone in the bottom of his left leg. In his diary, Booth wrote that he said, “Sic semper” although eyewitnesses thought he said “Sic semper tyrannis” and others “The South is avenged”. Only the screams of the ladies from the box suggested this wasn’t a part of the play; the audience began to realize what had happened when the officer yelled, “Stop that man”.

Booth ran out to the alley from backstage, pursued by audience members, where his groom Joseph “Peanuts” Burroughs was waiting outside, holding Booth’s horse. Booth struck Peanuts in the head with his knife, jumped onto his horse, and rode off.

Booth had gained entrance to the President’s box at the theater without any problem because the assigned bodyguard, John Parker, a Metropolitan Washington DC officer, was not where he was supposed to be: seated just outside in a passageway by the door. From where he sat, the bodyguard couldn’t see the stage, so after Lincoln and his guests settled in, he moved to the first gallery to enjoy the play. Later, he committed an even greater folly: at intermission, he joined the footman and coachman of Lincoln’s carriage for drinks in the Star Saloon next door to Ford’s Theatre. Booth was seated in the Star Saloon, drinking quite heavily. When Booth crept up to the door to Lincoln’s box, he knew there was no one on duty because he saw Parker drinking in the saloon.

Major Henry Rathbone attended the play at Ford’s Theater with the Lincolns and his fiancée, Clara Harris. He was invited only because General and Mrs. Grant turned down the invitation at a late hour. The general’s wife, however, had recently been the victim of Mary Todd Lincoln’s acid tongue and wanted no part of a night on the town with the First Lady. Grant had backed out citing the couple’s desire to travel to New Jersey to see their children. He attempted to stop the assassin but was seriously wounded by Booth, who slashed Rathbone’s left arm from his elbow to his shoulder.

All four of the people in that box would become tragic victims of that night. Major Rathbone married Clara—who also happened to be his stepsister—in 1867, but then he grew increasingly erratic and perhaps suffered from post-traumatic stress. Although they had 3 children, he was mentally anguished forever after by thoughts that he had not done enough to prevent the murder. Although appointed by President Arthur to be the Consul to Hanover, his mental health continued to decline. He threatened divorce frequently. He ultimately fatally shot and stabbed his wife and then stabbed himself five times. He was charged with murder but instead was declared insane and committed to a mental asylum for the remainder of his life. Mary Todd Lincoln, the fourth person present, was herself institutionalized in 1875.

The president had been mortally wounded; He was carried to a lodging house across the street from the theater. At about 7:22 the next morning, he died—the first U.S. president to be assassinated.

Seward

Another segment of the plot was to assassinate William Seward, the Secretary of State. Lewis Powell, a co-conspirator with John Wilkes Booth, forced his way into Seward’s house. Seward had been in a carriage accident 9 days previously, breaking his jaw. He was recuperating from a painful wound that prevented him from eating normally. The accident and Seward’s injuries were widely reported. Powell came to the door dressed well and claimed to be bringing pain medication that Seward’s doctor had prescribed. The servant answering the door was happy to take the medication but would not give the “messenger” entrance to the house. Powell pushed open the door and raced up the stairs to the bedroom, where he stabbed Seward several times before fleeing the scene. Seward was wearing a brace for his jaw injury that deflected the knife slashes. He also rolled over away from the killer and was only minimally injured in the chest and neck. Besides Seward, 8 people were stabbed and one hit in the head; these included four of Seward's children, a bodyguard, and a messenger. His son Frederick was hit in the head by a pistol when the gun malfunctioned; he spent 2 months in a coma. That night and the next morning, Seward deduced that Lincoln had been murdered. Seward heard church bells tolling; although the people around him tried to deny it, fearing the effect of inflicting emotional pain, Seward said, “Lincoln is dead because if he were alive he would have been the first to come to see me.”

Who was Booth? What was he planning?

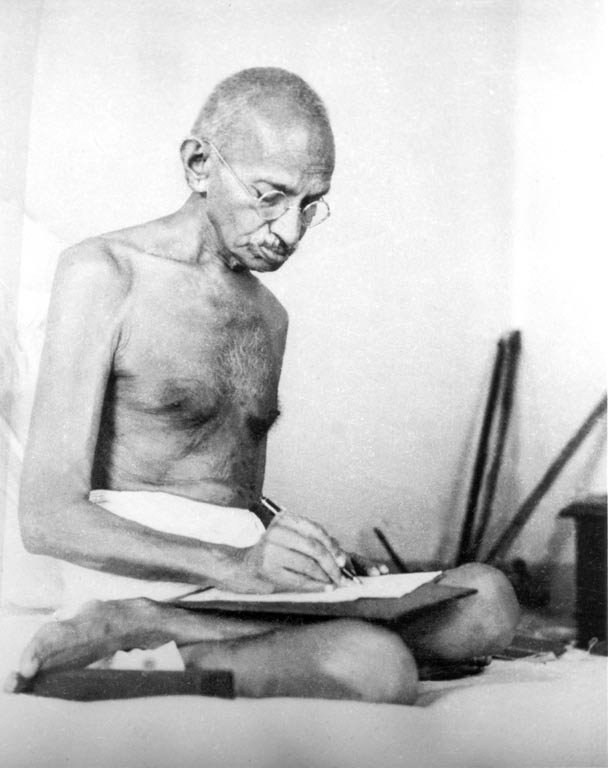

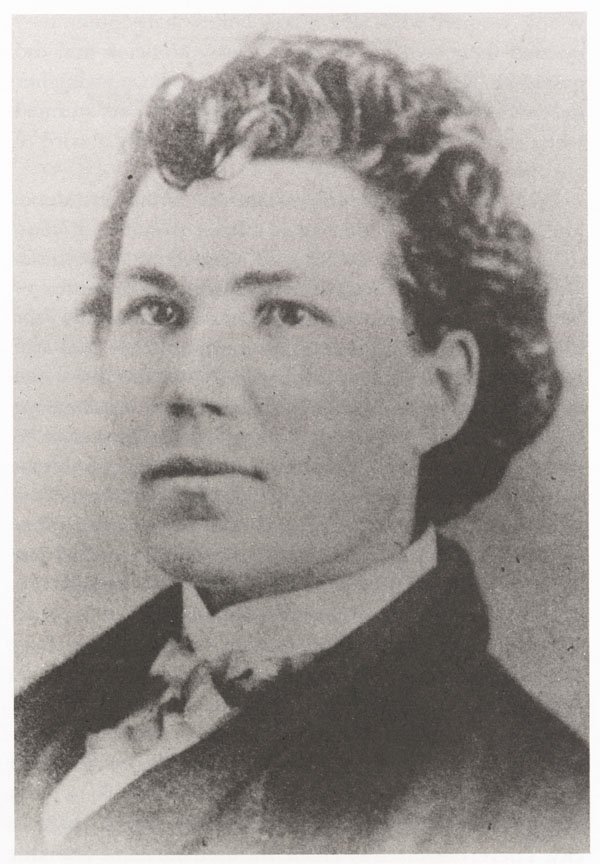

John Wilkes Booth was a famous actor, from a very prominent theatrical family. Many considered Booth’s father, Junius Brutus Booth, to be the finest Shakespearean actor of his generation, and Booth’s older brother, Edwin is commonly named among the greatest American actors of all time, Booth grew up in Baltimore. He was called “the handsomest man in America” by at least one critic.

His interest in politics, and particularly his partiality to slavery, developed at a young age. The rest of his family could not abide his politics, as they were all Union men. Booth became involved with the Knights of the Golden Circle in Baltimore. During the war, he chose to remain in the North despite his political persuasions as there were more options for actors in northern cities.

His anti-Union sentiments were fully displayed on an October 1864 trip to Montreal, a city noted for its southern sympathy and a notorious outpost of Confederate agents. On October 18th he checked into St. Lawrence Hall, an old Hotel known as the Confederacy’s Canadian center. Witnesses would later claim to have seen Booth talking with known agents and openly expressing contempt for Lincoln.

There, money from some source changed hands; a bankbook with $ 455 and three certificates of exchange from The Ontario Bank dated October 27th was found in his possession when he was killed. It is believed that he had already developed a general plan for the kidnapping of Abraham Lincoln at that point. Booth was known to have been in Montreal that day. The origin of these funds remains uncertain, especially regarding whether someone high up in the Confederate government had financed the assassination (Klein).

A witness at the 1865 trial of Booth’s accomplices testified that Patrick C. Martin accompanied Booth to the Montreal branch of the Ontario Bank, where Booth made a deposit and took bills of exchange. Martin was a Baltimore liquor dealer who had established a Confederate Secret Service base in Montreal in the summer of 1862. He had arranged blockade running and financial services benefitting Confederate interests. It is known that Booth tried to arrange the transfer of his theatrical costumes to Jamaica by Martin

Martin gave Booth letters of introduction to two southern Maryland physicians, Dr. William Queen and Dr. Samuel Mudd. These operatives were to assist him in escaping. In November, 1864. Booth deposited $1,500 in the Cooke Bank in Washington. He spent these funds between January 7 and March 16, 1865, to assemble his team.

The Plot

Booth had visited Bryantown MD in November and December 1864, allegedly to search for real estate investments. Bryantown is located 25 miles from Washington and about 5 miles from Dr. Mudd's farm. Of course, the real estate alibi was a cover; Booth's true purpose was to plan an escape route as part of the plan to kidnap Lincoln. Booth’s original idea was that the federal government would ransom Lincoln by releasing a large number of Confederate prisoners of war.

There, he met with Dr Mudd, an active participant in a confederate spy network. Booth met Mudd at St. Mary's Catholic Church in Bryantown during one of those visits, probably in November. Booth visited Mudd at his farm the next day and stayed there overnight. The following day, Booth purchased a horse from Mudd's neighbor and returned to Washington.

On December 23, 1864, Mudd traveled to Washington. There he met Booth again, where the two men, as well as John Surratt, Jr., and Louis J. Weichmann, had a conversation and drinks. They met first at Booth's hotel and later at Mudd's. According to a statement made by George Atzerodt taken while he was in federal custody on May 1, 1865, Mudd knew in advance about Booth's plans; Atzerodt was sure the doctor knew because Booth had "sent (as he told me) liquors & provisions... about two weeks before the murder to Dr. Mudd's."

It has been suggested that Booth heard Lincoln speak at his second inaugural address. Some photos appear to show him in the crowd wearing a top hat but perhaps also without. No one knows for certain if this individual is Booth, or even if Booth was present that day.

On March 17, Booth and a group composed of George Atzerodt, David Herold, and Lewis Powell, met in a Washington bar to plot the abduction of the president three days later. However, the president changed his plans, and the scheme was scuttled. General Robert E. Lee surrendered to the Union on April 9th at Appomattox Court House and the war was essentially over.

On the evening of April 11, the president stood on the White House balcony and delivered a speech outlining some of his ideas about reconstruction and bringing the defeated Confederate states back into the Union. Lincoln indicated a desire to give voting rights to some African Americans, such as those who had fought in the Union ranks during the war. He expressed a desire that the southern states would extend the vote to literate blacks, as well. Booth was in the small audience on the White House lawn listening. , “That means n____ citizenship,” he told Lewis Powell. “Now, by God, I’ll put him through. That is the last speech he will ever make.” Booth’s plot changed to murder at that moment. The conspirators altered their plan; the new plot was to kill Lincoln, Vice President Andrew Johnson, and Secretary of State William Seward on the same evening.

While visiting Ford's Theatre around noon to pick up his mail on April 14th, Booth learned that Lincoln and Grant were to visit the theater that evening for a performance of Our American Cousin. Booth had performed there several times, so he knew the theater's layout and was familiar to its staff. Recognizing this was a golden opportunity, Booth went to Mary Surratt's boarding house and asked her to deliver a package to her tavern in Surrattsville, Maryland. He also asked her to tell her tenant Louis J. Weichmann to ready the guns and ammunition that Booth had previously stored at the tavern.

The conspirators met for the final time at 8:45 pm. Booth assigned Powell to kill Secretary of State William H. Seward at his home, Atzerodt to kill Vice President Andrew Johnson at the Kirkwood Hotel, and Herold to guide Powell (who was unfamiliar with Washington) to the Seward house and then to a rendezvous with Booth in Maryland. Atzerodt backed out of his part to kill Johnson.

The Fibula Fracture

Many people believed that Booth broke his leg as a result of jumping from the presidential box onto the theatre stage from the impact of the jump to the stage, where he landed somewhat off balance. Some historians speculate that Booth may have broken his leg when the horse that he was riding, galloping away from the murder scene at a high rate of speed, tripped and fell on its left side. Perhaps his left leg was entangled in the flag that was draped in front.

Fibular fractures can be due to falls when landing incorrectly, but can also occur from a severely twisted ankle.The distance from the theatre box balcony to the stage floor today is approximately 12 feet. Some eyewitness accounts suggested that the original height was closer to 9 feet, and a sketch done soon after the assassination suggests the distance was 10 feet, 7 inches. The distance Booth jumped may never be accurately known since the theatre was renovated in 1866. The original box was completely demolished.

Fibular fractures are painful and often accompanied by ligament or tendon injuries. Swelling, tenderness, inability to bear weight, and numbness are common. This injury would be a serious impediment to one’s ability to walk without a limp or run normally.

Escape Route & Capture

After the assassination, Booth rode to Maryland with David Herold. The first place was Popes Creek on the Potomac River in southern Maryland, and then to the Surratt Tavern to pick up the weapons he had asked to be delivered there earlier. Finally, he went to the home of Dr. Mudd, who placed splints on Booth’s leg. It would have been impossible, as Mudd claimed, that he did not know this man, whom he had met on several occasions. Moreover, while Mudd may not have known about the assassination that night, he certainly did the next morning when he went into town; yet he told no one about his guests. Booth then left and they stayed at the home of Samuel Cox, and then in some woods on the north bank of the Potomac. There, Booth had access to newspapers and food. On April 22nd, they rowed across the river to Virginia, on the south side. They hid in a barn on Richard Garrett’s farm, as thousands of Union troops combed the area looking for them.

The assassination of Abraham Lincoln initiated a massive search to find the killers Secretary of War Stanton sent a telegram to his man, Lafayette Curry Baker, head of the federal intelligence service, called the US Secret Service. Curry was in New York City when Stanton ordered him to come to DC immediately and help find the murderer. The identity of the assassin was well established, but he remained at large. Despite being In a city with thousands of troops at the war’s end, and hundreds of police, Stanton sent out the signal for this particular man to help find him. “Come here immediately and see if you can find the murderer of the President,” Stanton telegraphed him. He took the train the next day.

Within two days he had arrested Mary Surratt, Lewis Paine, George Atzerodt, and Edman Spangler. He also had the names of the fellow conspirators, John Wilkes Booth and David Herold. His investigation method wasn’t to search for anyone. Instead, he planted moles in the ranks of the investigators. From them, he learned that the prime suspects were traveling south through the eastern Maryland counties of Prince George and Charles. Thousands of troops and uncounted civilians were involved in the manhunt. Stanton had put out a reward of $100,000 (about $1.8 million in today’s dollars). Every motivated civilian, detective, policeman, and Union officer hoped to strike it rich.

He happened to be in the offices of the War Department when he learned that two men identified as the fugitives had been seen making the Potomac crossing into Virginia near Mathias Point on April 22nd. He knew a great deal about the routes used by Confederate couriers and spies that operated in the Northern Neck and made an educated guess as to where Booth and Herold might be. He summoned two assistants in his office spread out a map on a small table and pointed to Mathias Point on the Virginia side of the Potomac. “He’s right in there,” pointing to a circle he drew on the map. “I want you to go to this place, search the country thoroughly, and get Booth.”

He sent Lieutenant Edward P. Doherty and twenty-five men from the Sixteenth New York Cavalry to capture Booth in Virginia, accompanied by Lieutenant Colonel Everton Conger, an intelligence officer. Several of his men knocked on doors, and asked about two men, one with a broken leg, for 12 hours. Finally, an ex-Confederate soldier named William S Jett was interrogated roughly. The man guided them and a cavalry squad to Richard H Garrett’s farm, where the cavalrymen discovered the fugitives in a tobacco barn on the morning of Wednesday, April 26, 1865.

Around 2:00 am the soldiers surrounded the barn, which was located about 60 miles south of Ford's Theatre near Port Royal, Virginia. Lieutenant Luther Baker yelled, "Surrender, or we'll fire the barn and smoke you out like rats! We'll give you five minutes more to make up your minds." Booth asked for time to decide. Finally, after some more give and take with the soldiers, Booth yelled, "Well, my brave boys, you can prepare a stretcher for me! I will never surrender!" After a short time, Booth said, "Oh, Captain, there's a man in here who wants to surrender awful bad." The barn door rattled, and David Herold's voice was heard saying he wanted to give up. Herold slowly came out and was slammed to the ground by the soldiers. He was hauled to a nearby tree and tied up with rope.

Still, Booth would not come out. Using straw and brush, Conger set the barn on fire. Booth was visible to the soldiers because the barn was full of cracks and knotholes. They could see him moving about the burning barn holding his carbine and crutch. At this moment, Corporal Boston Corbett shot Booth through the neck. Booth was paralyzed and barely alive. With difficulty, Booth was able to speak. He said, "Tell Mother I died for my country." A local doctor, Dr. Charles Urquhart, Jr., who had been a physician in nearby Port Royal since 1821, arrived on the scene and indicated the wound that had punctured Booth's spinal cord was fatal. Sometime around 7:00 A.M. Booth looked at his hands and moaned, "Useless! Useless!" Those were probably the last words Booth spoke before dying.

Booth was pronounced dead at 7:15 A.M. A search of his body turned up a pair of revolvers, a belt and holster, two knives, some cartridges, a file, a war map of the Southern States, a spur, a pipe, the Canadian bills of exchange, a compass with a leather case, a signal whistle, an almost burned up candle, pictures of five women - four actresses (Alice Grey, Helen Western, Effie Germon, and Fanny Brown) and his fiancée, Lucy Hale (the daughter of ex-Senator John P. Hale from New Hampshire), and an 1864 date book kept as a diary. These items found on his person still exist. They are owned by the National Park Service and held at the Ford’s Theater Museum. They have a long history in themselves.

Lt Col Conger brought Booth’s possessions back to Curry, who turned them over to Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton, who used them as trial evidence for the assassins' accomplices. Except for one thing: Booth’s diary. When it reappeared in 1867, it was missing 18 pages. No one knows who cut those out of the book, or why. Stanton claimed it was given to him like that. It might be that the missing pages in Booth’s diary told who Booth was working for, and the whole story of the plot; and may have incriminated very prominent people, such as Andrew Johnson, as part of the kidnapping scheme. Some have speculated that Stanton destroyed the pages because his own name appeared in it. Yet another theory is that the missing pages included the names of people who had financed the conspiracy; it later emerged that Booth had received a large amount of money from a New York-based firm to which Stanton had connections.

The other conspirators were captured the day after the assassination outside Surratt’s boarding house, except for John Surratt, who fled to Canada. Powell was caught purely by accident, as he approached the boarding house not knowing Union troops were inside; he was missing his hat (found in the Seward home) and had blood stains on his clothes. On July 7, after a military court trial. George Atzerodt, Lewis Powell, David Herold, and John Surratt’s mother, Mary, were hanged in Washington. The execution of Mary Surratt is believed by some to have been a miscarriage of justice. Although there was proof of her involvement in the original abduction conspiracy, it is clear that her deeds were minor compared to those of the others who were executed. John was eventually tracked down in Egypt and brought back to trial, but with the help of clever lawyers, he won an acquittal in a civilian court.

On June 29, 1865, Mudd was found guilty with the others. The testimony of Louis J. Weichmann was crucial in obtaining the convictions. Mudd escaped the death penalty by one vote and was sentenced to life imprisonment. He was later pardoned by President Andrew Johnson in 1869.

Some contemporary historians make a case that Dr Mudd should be exonerated. There is no definitive evidence to support that he knew that Lincoln was assassinated nor that Booth had committed a crime. There is evidence that he was involved in the kidnapping plot though. The key issue is that he lied about knowing Booth, and how much he knew about the plot, and delayed reporting Booth's presence. That made him guilty of conspiracy and being an accomplice, but saved him from the death penalty. Interestingly, others also knew about the kidnapping plot who weren't convicted of the murder. Legally his lack of planned involvement in the assassination mitigates any participation after the fact. Then there is his Hippocratic oath, which obligated him to treat Booth's leg, although not to maintain his anonymity. Moreover, although Weichmann tied the acquaintance of Booth to Mudd, he did not claim to know what they discussed.

Baker was promoted to Brigadier General and received all the publicity and the reward for the capture. But several years later he died under mysterious circumstances, further suggesting a conspiracy of profound intrigue.

Was the Booth capture a hoax?

Booth's remains were sewn up in a horse blanket and placed on a wide plank. An old market wagon was obtained nearby, and the body was placed in the wagon. The body was taken to Belle Plain. There it was hoisted up the side and swung upon the deck of a steamer named the John S. Ide and transported up the Potomac River to Alexandria where it was transferred to a government tugboat. The tugboat carried the remains to the Washington Navy Yard, and the corpse was placed aboard the monitor Montauk at 1:45 A.M. on Thursday, April 27. Once aboard the Montauk, Booth's remains were laid out on a rough carpenter's bench. The horse blanket was removed, and a tarpaulin was placed over the body.

Several witnesses were called to identify the body. A sketch that appeared in Harper's Weekly on May 13, 1865, shows the process. Several people who knew Booth personally are known to have identified the body. One of these people was Dr. John Frederick May. Sometime before the assassination, Dr. May had removed a large fibroid tumor from Booth's neck. Dr. May found a scar from his operation on the corpse's neck exactly where it should have been. Charles Dawson, the clerk at the National Hotel where Booth was staying, identified the initials "J.W.B" pricked in India ink on the corpse's hand. As a boy, Booth had his initials indelibly tattooed on the back of his left hand between his thumb and forefinger. Alexander Gardner, the well-known Washington photographer, was also among those who positively identified the remains, as were his assistant Timothy O’Sullivan, and Seaton Munroe, a prominent Washington attorney.

There were five witnesses to the post-mortem: Charles M. Collins, Charles Dawson, Seaton Munroe, John Frederick May, and William Wallach Crowninshield, Surgeon General Joseph K. Barnes, Dr. Joseph Janvier Woodward, and Dr. George Brainard Todd performed the autopsy aboard the Montauk. Booth’s third, fourth, and fifth cervical vertebrae, which were removed during his autopsy, are housed (not on public display) at the National Museum of Health and Medicine at the Walter Reed Army Medical Center. An additional fragment from Booth's autopsy (tissue possibly cleaned off the cervical vertebrae) is in a bottle in the Mütter Medical Museum of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia.

******************************************************************************

Dr. Barnes wrote the following account of the autopsy to Secretary of War Edwin Stanton:

“Sir,

I have the honor to report that in compliance with your orders, assisted by Dr. Woodward, USA, I made at 2 PM this day, a postmortem examination of the body of J. Wilkes Booth, lying on board the Monitor Montauk off the Navy Yard.

The left leg and foot were encased in an appliance of splints and bandages, upon the removal of which, a fracture of the fibula (small bone of the leg) 3 inches above the ankle joint, accompanied by considerable ecchymosis, was discovered.”

The cause of death was a gunshot wound in the neck - the ball entering just behind the sterno-cleido muscle - 2 1/2 inches above the clavicle - passing through the bony bridge of fourth and fifth cervical vertebrae - severing the spinal chord (sic) and passing out through the body of the sterno-cleido of right side, 3 inches above the clavicle.

Paralysis of the entire body was immediate, and all the horrors of consciousness of suffering and death must have been present to the assassin during the two hours he lingered.”

****************************************************************************

Some have suggested that Booth actually was never captured and escaped to Texas, where many years later his “corpse” was a great sideshow hit. This photograph is searchable online, but it is complete nonsense: the Booth autopsy was well attended and documented.

The corpse was again positively identified in February of 1869 when Booth's remains were exhumed and released by the government to the Booth family. At that time an inquest was held at Harvey and Marr's Parlor in Washington. Booth's corpse was taken to Baltimore for burial and was positively identified by many people including John T. Ford, He ry Clay Ford, and Joseph Booth, John's brother.

Did you find that piece interesting? If so, join us for free by clicking here.

References

https://www.thevintagenews.com/2016/01/18/46415/

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/lincolns-missing-bodyguard-12932069/

https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/john-wilkes-booth-shoots-abraham-lincoln

https://www.historynet.com/dr-samuel-a-mudd/

https://globalnews.ca/news/1611968/lincoln-assassin-john-wilkes-booths-canadian-connection/

https://lincolnconspirators.com/picture-galleries/found-on-booth/

https://lincolnconspirators.com/2012/05/31/booth-at-lincolns-second-inauguration/

https://www.onthisday.com/photos/john-wilkes-booth-at-lincolns-inauguration,

https://www.nps.gov/foth/learn/historyculture/faq-the-assassin.htm#:~:text=Many%20people%20believed%20that%20John%20Wilkes%20broke%20his,on%20something%20and%20fell%20on%20its%20left%20side.

https://www.fords.org/visit/historic-site/museum/

https://www.militaryimagesmagazine-digital.com/2022/06/05/scoundrel-the-rise-and-fall-of-union-spy-chief-lafayette-curry-baker/

American Brutus by Michael Kauffman On page 348 (first edition hardcover)

https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/john-wilkes-booth-shoots-abraham-lincoln

https://columbialawreview.org/.../the-law-of-the-lincoln.../

https://www.rogerjnorton.com/Lincoln83.html

Further Reading

· https://rogerjnorton.com/Lincoln40.html

· Michael W Kauffman, American Brutus: John Wilkes Booth and the Lincoln Conspiracies. Random House, 2004