The leaked British government plans for a no-deal Brexit show a Britain in peril. In the past, as in the case of preparations for the event of a Soviet nuclear attack, the government has been well advised to keep secrets from the public lest they expose the true extent of the inadequacy of their plans.

Here, Jack Howarth looks at Brexit planning in the context of government planning for a nuclear attack in the Cold War.

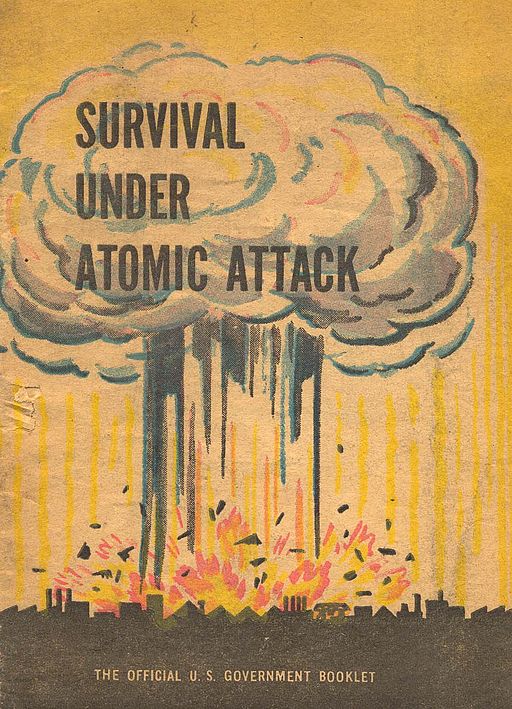

There was frequent guidance in the Cold War related to what to do in the event of a nuclear attack, such as this US Government booklet.

The leaked Operation Yellowhammer document, outlining the British government’s planning for a no-deal Brexit, paints a grim picture of Britain’s future. It shows planners preparing for food shortages, economic disruption, and civil unrest; ‘wartime implications, in peacetime’, according to one MP.

British Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s government claims the consequences shown are merely a worst-case scenario, not a prediction. Still, one imagines the government would rather these plans have remained secret.

After all, why scare the public with what only might happen?

Planning for a Soviet nuclear strike

This line of argument has a history. Decades ago, the British government was similarly engaged with planning for full-scale disaster: economic collapse, unprecedented health crises, and public disturbances threatening the rule of law.

Then, the preparations being made behind closed doors were for how Britain might look after an expected nuclear strike by the Soviet Union. Strategic exercises, devised at the behest of the Callaghan and Thatcher governments, were role played to ensure a future for the British state in the event of a catastrophe.

It was widely known that entertaining any hope for the survival of the public-at-large was futile. The advice given to the populationwas usually ill-considered, sometimes grimly amusingand, scoring points for some contemporary politicians, flew in the face of all guidance given by the experts.

The decimation of the population, though, was not seen as good reason to not ensure the continuity of government.

While it was assumed the Cabinet would either be preoccupied in scrabbling for a retaliation, or be entirely obliterated, declassified civil service records show plans being laid out for the proposed structure of the rest of the state infrastructure after an attack.

In order to avoid anarchy, disorder and delays, officials planned a new, regionally devolved government. County council chief executives would become substantially empowered. A Britain divided into twelve regional zones would emerge, each being ruled essentially as their new leader saw fit.

As the test runs played as war games by civil servants, military officials, and those who would ultimately take up power progressed, many bemoaned the lack of clarity of government figures. Confusion reigned, with the only agreement amongst the players tending to arise around the need for the future leaders to ‘virtually have life and death authority over the people of the county’. In this, at least, the government was obliging: an emergency powers bill was prepared ready to be pushed through Parliament at a moment’s notice.

None of those involved in the actual work of the exercises was under any delusion of bravado; none imagined they could actually face down the threat. Even those who were to be given the role of ruling their region knew they were planning for the impossible.

Fortunately for the government of the day, the scenarios envisaged by these plans remained largely unknown to the public. Attempts to publish them led to criminal prosecution. Awareness of them might compromise Britain’s power abroad, or embarrass the nation in front of the enemy, it was said.

Planning in perspective

Reading the correspondence involved now, one might agree that the government was sensible to not disclose its plans. Obvious wartime disadvantages aside, civil defense planners already faced staunch opposition from local government and resurgent protest movements. Had the public known the depth of inadequacy of the government’s plans, the support for the enshrined policy of mutually assured destruction may have ebbed to the extent of requiring reconsideration.

To protect government policy, the officials responsible for contingency planning decided that the ‘balance of advantage’ weighed against any public disclosure, lest they alarm the public. There was, they reasoned, always the possibility that their work may be unnecessary, that disaster may be averted.

What do you think of Cold War nuclear planning? Let us know below.

Jack Howarth is a graduate of the University of Exeter and is currently a postgraduate student at Oxford Brookes University, having been awarded the de Rohan Scholarship to continue his research into contemporary history.