In 1916, Irish republicans led the Easter Rising that sought to end British rule and create an independent Ireland. As part of this they read the 1916 Proclamation or Easter Proclamation, a document that proclaimed Irish independence. Here, Jenny Snook explains the events and their lasting importance.

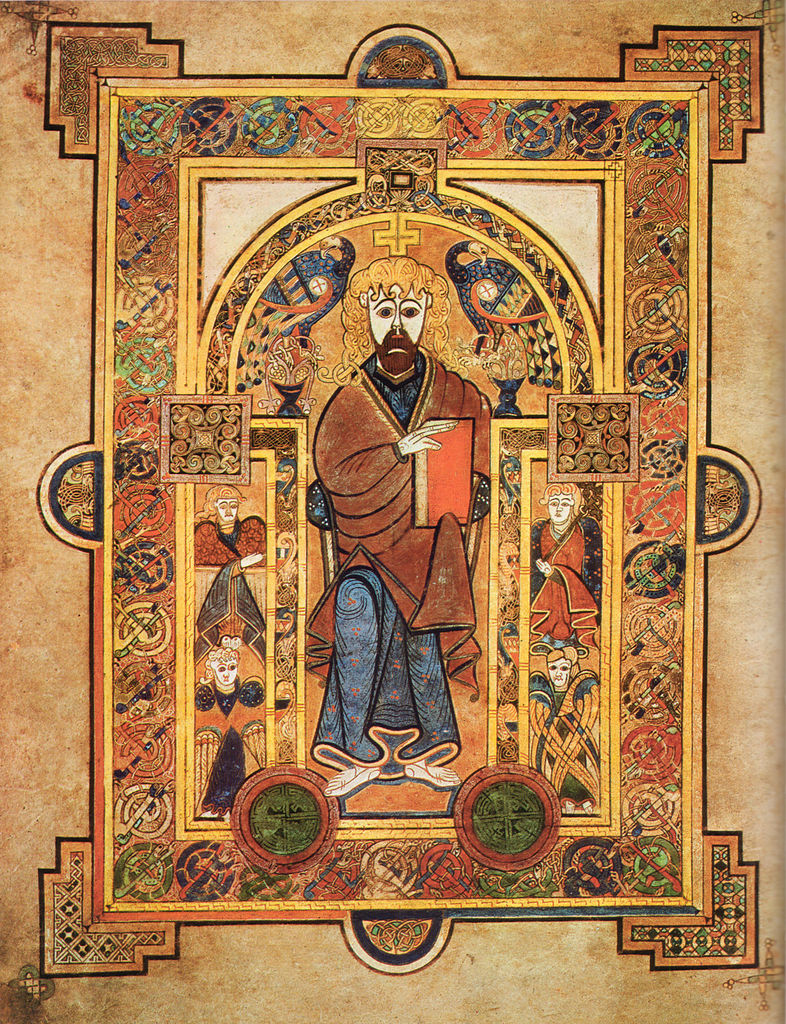

Birth of the Irish Republic by Walter Paget.

In 1949, Ireland was officially declared a republic. In 2008, an auction of independence memorabilia took place in Dublin, with sales reaching over €2 million (around $2.3 million). One of the pieces sold was an original copy of the 1916 Proclamation of the Irish Republic, selling for €360,000 (c. $410,000).[1] This was a declaration read out over a century ago by a member of the Irish Volunteer Force. Although not an official declaration, it is now seen as a symbolic gesture which motivated the Irish people to stand up for their right to obtain independence and is still celebrated today.

The country was first captured by the British in 1169 and Republican ideas immerged centuries ago from people willing to use force to free Ireland from the British Empire. The 1798 Rebellion is known as one of the most disturbing, violent events in Irish history, significantly inspired by French republicanism. The Easter 1916 Rising is commonly recognized as the turning point in the development of modern Ireland.

The Irish Volunteer Force (IVF)

The Irish Volunteer Force (IVF) was a military republican organization first founded in 1913 and was the group most significantly involved in the Rising. They were formed as a direct response to the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF), established in 1912. The UVF opposed any republican ideas and wanted to remain part of the British Empire. The Irish Citizen Army (ICA) were a smaller force that took part in the Rising, set up as the armed wing of workers on strike during a labor dispute known as the “Dublin Lock Out”.

The Easter 1916 Rising displayed a willingness to resort to violence to make Ireland a republic. While the British were more concerned with the problems of World War One, a popular slogan that became linked with the IVF was:

England’s difficulty is Ireland’s opportunity.

Conscription was never implemented in Ireland, but over 200,000 Irishmen still chose to enlist in the British army during the war. Members of the UVF were willing to stand up for their country but many members of the IVF had no desire to support a country that they did not want to be a part of.

It was their plan to take control of the General Post Office (GPO) on O’Connell Street in Dublin City Center, while taking over some other sites to block the main routes into the city. It was outside the GPO that Padraig Pearse would stand up and read the Proclamation of the Irish Republic.

Most of the actions taken involved rebels taking possession of buildings along these routes and then defending themselves from the British soldiers. It does not appear as though they expected victory but it seems more of a symbolic action that people still admire today. A famous statement made by Padraig Pearse, on 25th April was:

Victory will be ours, even though victory will be found in death.[2]

Problems from the Beginning

Although members of the IVF all had the same goal of turning Ireland into a republic, they held vastly different views over whether the Rising was a good idea. Some thought that more time was needed to assemble followers and plan mass resistance. There were others who believed the best thing to do was strike, there and then, without worrying about the risks. Sean MacDermott was one of the leaders of the Rising who supported this view.

Opposing MacDermott, Eoin MacNeill felt this was a reckless and counter-productive idea that held no real benefits. One of the reasons MacNeill finally agreed to support the Rising was the reassurance that Germany would be sending over a shipment of weapons. The Aud carried 20,000 rifles, 3 machine guns, and ammunition over to Co. Kerry in southwest Ireland. Unfortunately, this ship was intercepted by the Royal Navy and the captain decided to scuttle the ship, rather than letting it be seized by the enemy. When MacNeill found out what had happened but realized that the Rising was still going ahead, he issued a ‘countermanding order’ to cancel their plans.

While he sent an order to cancel the rebellion beginning on Sunday, the Military Council met, agreeing to change the day until Monday, causing confusion. This disagreement was one of the main reasons why a lot of the people who had planned to attend on Sunday did not even turn up the next day.

None of the leaders were professional officers and they did not have enough support or sufficient artillery to seize power. There were about 1,300 members of the IVF involved and 219 from the ICA,[3] with a central meeting point outside the headquarters of the Irish Transport and General Workers Union at Beresford Place. Under Padraig Pearse and James Connolly (founder of the ICA), a force was sent out to take control of the GPO on O’Connell Street.

Four battalions were set up to occupy different parts of the city. The first of these battalions was led by Ned Daly and took possession the Four Courts, home of the country’s law courts. Under Thomas MacDonagh, the second battalion met at St. Stephen’s Green, before taking control of the Jacob’s Biscuit Factory. Eamon de Valera oversaw the third battalion, occupying Boland’s Bakery and under Eamonn Ceannt, the fourth battalion focused on a workhouse, ‘the South Dublin Union.’

Although their defensive locations were strong, these groups were positioned too far apart and there were not enough people involved to offer support if another was attacked. Although the initial British reaction was shock, martial law was quickly declared, leading to the gradual isolation and surrender of these rebel positions.

The Reading of the Proclamation

After taking control of the GPO, it was here that Padraig Pearse read out the Proclamation of the Irish Republic on April 24th, 1916. This was signed by James Connolly and 6 members of the IVF: Thomas J. Clarke, Eamonn Ceannt, Thomas MacDonagh, Joseph Plunkett, Padraig Pearse, and Sean MacDermott, written primarily by Pearse and Connolly.

A supporter of the Gaelic League (dedicated to protecting Irish language and culture), Pearse was also an educational reformer. He described the national school system as a ‘murder machine’ set out to destroy the Irish language.[4] Responsible for setting up several experimental, Irish speaking schools, he stated:

A country without language is a country without soul.[5]

There was only a small crowd present to listen to the reading of the proclamation. They did not show much enthusiasm when he tried to justify what the rebels were doing and what they hoped to achieve from it. The opening sentence read:

In the name of God and the dead generations from which she receives her old tradition of nationhood, Ireland, through us, summons her children to her flag and strikes for her freedom.

He tried to assure the crowd that becoming a republic:

Guarantees equal rights and equal opportunities to all its citizens and declares its resolve to pursue the happiness and prosperity of the whole nation and of all its parts, cherishing all the children of the nation equally.[6]

Pearse may not have succeeded in motivating the crowd at the time, but was correct when he said later that week that:

When we are all wiped out, people will blame us. In a few years they will see the meaning of what we tried to do.[7]

Lasting Effects of the 1916 Rising

By Friday, it was clear they could not last much longer at the GPO. Pearse ordered female volunteers to leave and by 7pm was forced to evacuate himself. At 8pm, the remaining rebels gathered to sing Ireland’s national anthem: “The Soldier’s Song”. After their surrender, 3,430 men and 79 women were arrested and while about 2,700 prisoners had been released by August 1916, there was no escape for the leaders. [8]

Between May 3 and May 12 all of the 14 leaders were shot dead, except for Eamon de Valera, who was officially a US citizen, moving over to Ireland at the age of two. The British might have sentenced these men to death to try and restore law and order, but all they really succeeded in doing was to turn most of the Irish public against them. Even though the majority of those arrested were released within a few months, there was still much resentment shown by those believing these people should not have been locked up in the first place. In 1917, support for Sinn Féin (Ourselves), a political party dedicated to Irish independence, grew rapidally. After his release, De Valera became a national icon. Serving as Taoiseach from 1937-1948, 1951-1954, and 1957-1959, he went on to serve as president of Ireland between 1959 and 1973.

Unlike the small crowd that first listened to Padraig Pearse read out the proclamation in 1916, on March 27, 2016, hundreds of thousands listened to it being read out again outside the GPO by Captain Peter Kelleher, to mark the 100-year anniversary of the 1916 Rising. This is probably the most celebrated scene in Irish history which Irish people today are proud to celebrate. Well-known and passionate supporters of the Rising include Irish poet W. B. Yeats, named one of the greatest poets of the 20th century. The last lines of his poem ‘Easter 1916’ (1921) read:

MacDonagh and MacBride

And Connolly and Pearse

Now and in time to be,

Wherever green is worn,

Are changed, changed utterly:

A terrible beauty is born.[9]

How important do you think the 1916 Proclamation was to achieving Irish independence? Let us know below.

[1] https://www.irishtimes.com/news/proclamation-copy-sells-for-360-000-1.913576

[2] Pritchard, p42

[3] https://www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/easterrising/profiles/po14.shtml

[4] Townshend, p71

[5] Pritchard, p8

[6] https://irishrepublican.weebly.com/proclamation.html

[7] https://www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/easterrising/profiles/po11.shtml

[8] https://www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/easterrising/aftermath/af01.shtml

[9] https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/43289/easter-1916

Bibliography

· Kenny, Michael: The 1798 Rebellion (1996). Town House and Country House. Dublin.

· Killeen, Richard: A Short History of the 1916 Rising (2009). Gill & Macmillan Ltd. Dublin

· Pritchard, David: A Pictorial Guide to the 1916 Easter Rising (2015). Real Ireland Design. County Wicklow, Ireland.

· Townshend, Charles: Ireland: The 20th Century (1999). Hodder Arnold. London.

· https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/43289/easter-1916 Easter 1916, by William Butler Yeats.

· https://irishrepublican.weebly.com/proclamation.html Copy of Proclamation.

· https://www.irishtimes.com/news/proclamation-copy-sells-for-360-000-1.913576 Proclamation Copy Sells for €360,000. (Apr 16th, 2008).

· https://www.rte.ie/news/ireland/2016/0327/777698-easter-rising/ Massive Crowds Line the Streets of Dublin for 1916 Parade (March 28th, 2016).

· https://www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/easterrising/profiles/po11.shtml 1916 Easter Rising Profiles: Patrick Pearse: 1879-1916.

· https://www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/easterrising/profiles/po14.shtml The Irish Citizens Army

· https://www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/easterrising/aftermath/af01.shtml The Executions