General Henry Knox (1750-1806, US Secretary of State for War from 1789 to 1794) played a key role in the American Revolutionary War. During the 1776 Siege of Boston he had a brilliant idea that manifested into the perilous journey of his noble train of artillery. Elizabeth Jones explains.

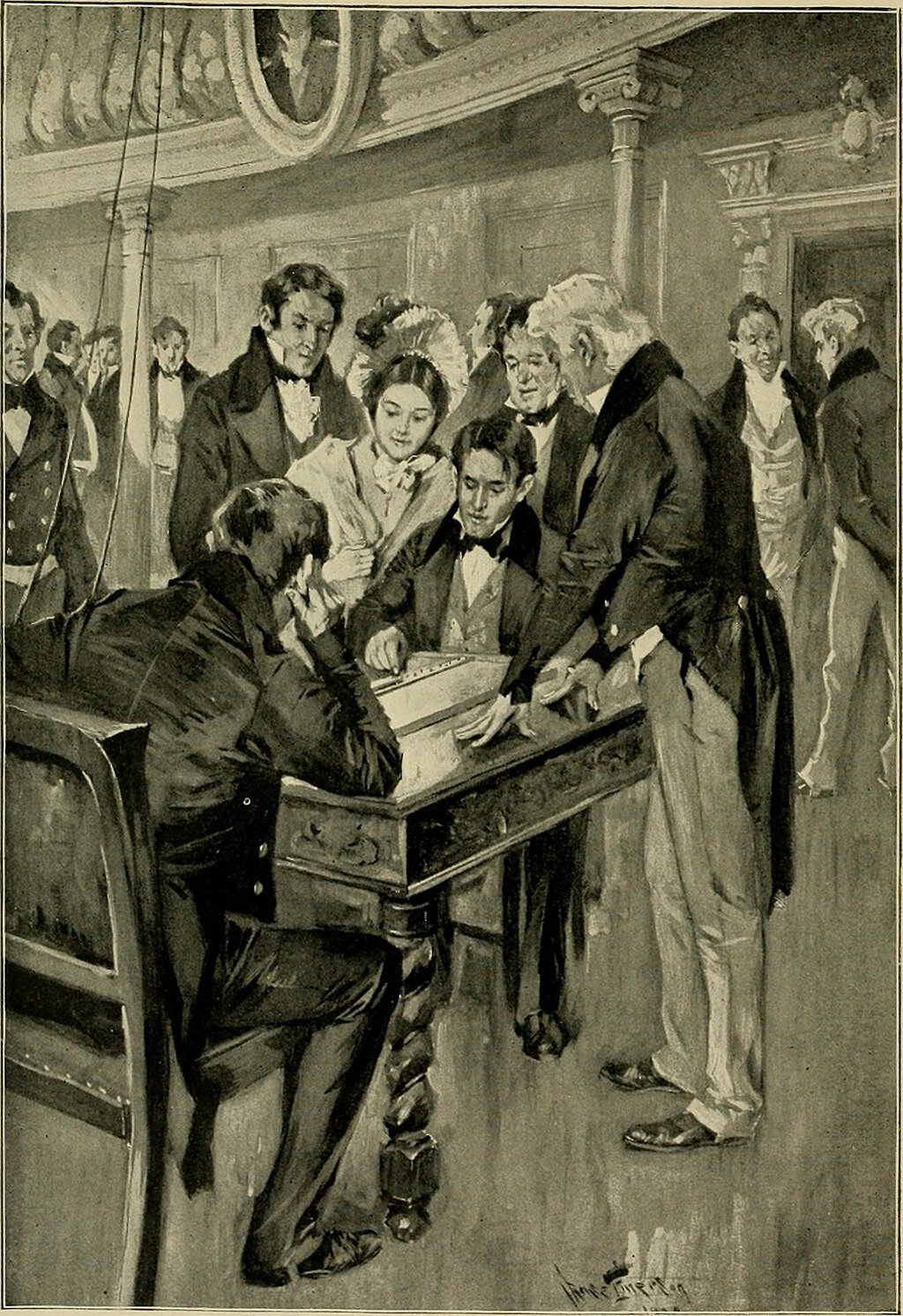

A portrait of Henry Knox from the 1780s. Painting by Charles Willson Peale.

Henry Knox was larger than life. Clocking in at over six feet and weighing more than 300 pounds, he was a giant during his lifetime and remains a giant in Revolutionary War history over 200 years after his death. And not only was he big, but in November 1775, he also had big problems. He had to find a way to move over 60 tons of artillery and munitions across the frozen 300 miles between Fort Ticonderoga and the city of Boston, which was under siege by the Americans due to the occupation of Boston by British forces.

Needless to say, the outcome looked grim. Without the firepower provided by the cannons and howitzers captured at Ticonderoga by Ethan Allen and his Green Mountain Boys in 1775, the revolutionaries stood little chance of freeing Boston from her shackles. But Henry Knox wasn’t going to stand idly by while the British Army occupied his hometown.

Henry Knox, patriot and bookseller

Henry Knox was a first-generation American born in Boston in 1750. His formal education ended at age twelve when his father abandoned the family, and to support his mother he went to work as a clerk in a bookstore. As a result of his early and constant exposure to books, he became a voracious reader and educated himself on topics ranging from military strategy to advanced forms of mathematics.

Knox continued working in the bookstore, but he also made time for mischief, running with some of Boston’s notorious street gangs. At 18, Knox joined an artillery company presciently named The Train. He served in the company for several years, and once injured himself by shooting off two of his own fingers.

Knox opened his own bookstore in 1771 at the age of 21 and operated it until tensions between the British and their unruly American colonies reached a boiling point at Lexington and Concord on April 15 and 16, 1775.

Siege of Boston

The British forces took control of the city following the “shot heard ‘round the world” and Knox and his wife Lucy were forced to flee Boston, leaving the bookstore to be looted and vandalized. Knox immediately enlisted in the militia that was laying siege to the occupied city and served as an engineer, building fortifications.

Following the Battle of Bunker Hill, Knox was recognized for his work by the new Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army, General George Washington, but he still remained without a commission into the Army proper. Still, he continued to serve valiantly, even though the siege seemed to be going nowhere fast.

Besides, he had an idea. One that just might be crazy enough to work.

The noble train of artillery

On May 10, 1775, not one month after the fighting between the British and the Americans began in earnest, Ethan Allen and his Green Mountain Boys (including then-Colonel Benedict Arnold) captured Fort Ticonderoga in upstate New York from the British, and with it an arsenal of heavy artillery. Ticonderoga was then largely managed from afar by Arnold and used intermittently by other American forces. But one man remembered.

Henry Knox, still without his commission, approached General Washington with the idea of ending the siege of Boston by using the 60-ton arsenal that remained at Fort Ticonderoga. The only problem was that the feat was a logistical nightmare, especially considering the level of sophistication of the transportation available at the time. But Washington believed in the still-green Knox and gave his plan the green light. So Knox set out from Boston with a team of men, animals, and vehicles to bring the guns of Ticonderoga to the city under siege in a convoy.

The recovery operations began in earnest on November 17, 1775, when the company left Boston. It arrived at Fort Ticonderoga on December 5th, and the team promptly began loading the nearly 60 guns and accompanying munitions and stockpiles. The easiest part completed, the company set back for Boston with the guns in tow in the midst of an 18th-century winter.

The elements were unforgiving, but the terrain was even more so. Bodies of water and mountain ranges stood between Knox and his destination, but Knox refused to be deterred. They reached the northern tip of Lake George on the cusp of it freezing, which would have made the crossing impossible. The guns were loaded onto the ships, with many of them being loaded onto a ship called a gundalow.

The challenges begin

The gundalow sank near the lake’s southern shore. Nearly 120,000 pounds of desperately-needed munitions lay on a ship near the bottom of a rapidly-freezing lake. Most people would have been disheartened and abandoned the entire endeavor, but Henry Knox wasn’t most people. The determined man worked with his team to bale out the sunken gundalow and recover the guns from Lake George.

The company reached the outpost of Fort George, and Knox found time to pen a quick letter to General Washington, stating that he hoped “to be able to present your Excellency a noble train of artillery”. The name stuck. Henceforth the expedition to bring the guns of Ticonderoga to Boston came to be known as the noble train of artillery.

Upon leaving the fort, the noble train of artillery had to cross a river, upon which sleds holding the guns were dragged. Suddenly the strong ice began to crack, and guns fell through the ice to the bottom of the river. Once again, Knox refused to abandon even a few pieces of artillery, and once again the guns were raised from the bottom of a body of water.

It would seem as if the worst was behind Knox and the noble train, but they still had to cross the Berkshires, an unforgiving mountain range that was covered in ice and snow. The crossing was difficult and the elements worked against them at every turn, but the noble train of artillery persevered, and they reached the other side of the mountain range, and on January 25, 1776, the company reached Boston, much to Washington’s relief.

Lifting the Siege

The guns gave the Americans a much-needed edge, but there was still work to be done. Artillery relentlessly pounded the city, until, in the dead of night, Washington ordered the guns to be positioned upon the twin peaks of Dorchester Heights in present-day South Boston. This strategy, along with Knox’s perseverance, led to the departure of the British from the city on March 17, 1776. To this day, March 17 is celebrated in South Boston as Evacuation Day.

Knox finally received his commission into the Continental Army and was eventually promoted to the rank of major general, becoming the youngest in the army. He served the majority of his Revolutionary War career as the American chief of artillery and was appointed by President Washington to become the first Secretary of War. Knox died on October 25, 1806.

Conclusion

General Henry Knox was more than just a trusted right-hand to General Washington and an able artillery chief for the Revolutionary Army. He was a visionary whose forward-thinking and willingness to take risks ended the Siege of Boston, ultimately moving the needle of independence forward.

What are your thoughts on General Knox? Was he brilliant or a mad-man, or both? Comment below to let us know what you think about the fabled bookseller-turned-general.

References

https://www.masshist.org/database/viewer.php?item_id=463&pid=15

1776 by David McCullough

Henry Knox: Visionary General of the American Revolutionby Mike Puls