The American Civil War (1861-65) saw a breakthrough in various technologies. One of particular importance was the telegraph, a communication technology that had grown greatly in significance in the years before the US Civil War broke out. Here, K.R.T. Quirion concludes his three-part series on the importance of the telegraph in the US Civil War by looking at the role of the telegraph in the later years of the Civil War and its importance in the Union’s victory.

You can read part 1 in the series on the history of the telegraph in the 19th century here and part 2 on the telegraph in the early years of the US Civil War here.

Wagons and men of the U.S. Military Telegraph Construction Corps. Brandy Station, Virginia, 1864.

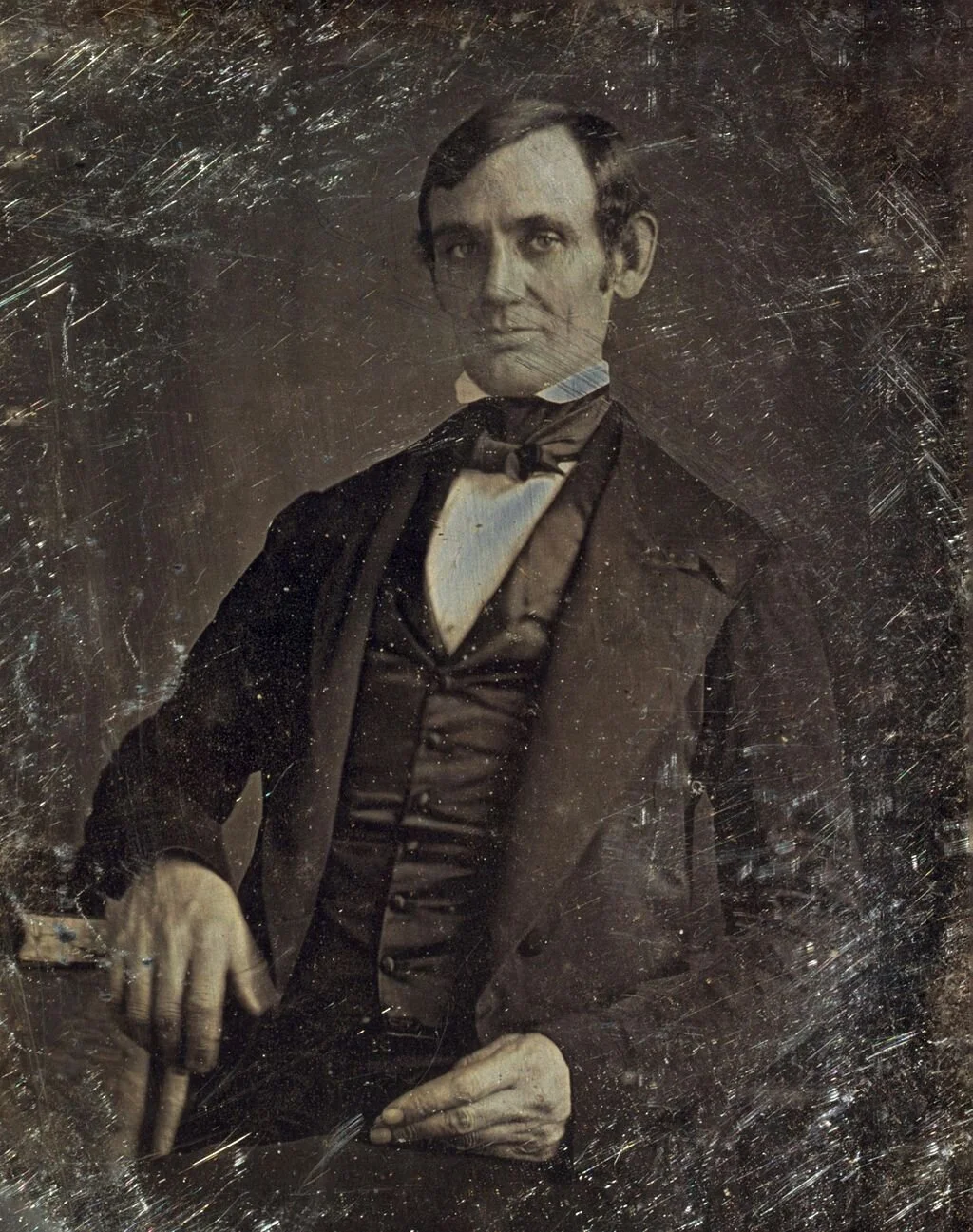

President Lincoln in the Telegraph Office

As an early adopter of the telegraph, Lincoln realized the importance of building a strong telegraphic infrastructure within the government and the military. With the Union facing the prospect of a 1,000-mile battle front, the telegraph gave Lincoln an unprecedented ability to “converse with his military leaders in the field as though he were in the tent with them” and power to “assume the role of commander-in-chief in a more titular sense.”[1]

Before Lincoln could exercise any degree of control over the nation’s dispersed military forces, it was necessary to organize the telegraphic capabilities of the Union. At the start of the Civil War all government telegraphs passed through one central communications hub, not even the War Department had its own separate line. [2]The organization of the USMTC soon remedied that deficiency when its headquarters were established inside of the War Department. By March of 1862, the telegraph had become so vital to the prosecution of the war that Secretary Stanton moved the USMTC telegraph office into to the “old library room, on the second floor front…adjoining his own quarters.”[3]In short order, the telegraph office of the War Department became Lincoln’s “Situation Room, where the president not only monitored events through incoming messages but also initiated communications directly to the field.” Lincoln spent more time in the telegraph office than in any other location during his presidency.[4]

Lincoln Takes Command

At first, Lincoln’s telegraphs were few. In the last six months of 1861, Lincoln sent only thirteen telegrams.[5]Despite this infrequency, the President exhibited no qualms about using the telegraph to “issue instructions regarding the disposition of troops.”[6]In these early telegraphs, Lincoln began exercising the authority of the commander-in-chief in a direct way. In one telegraph to John C. Fremont, the President ordered the General to begin deploying his troops in Kentucky. [7]Lincoln even went so far as to countermand Fremont’s own dispensation of his troops. [8]These first forays in taking direct command of Union troops were on a “glimmer of what was to happen.” [9]By 1862, the president had begun using the telegraph as means of directly communicating with commanders in the field without the filter of their commanding general. [10]Part of this direct action by Lincoln was brought about by has frustration with General George B. McClellan’s hesitancy to engage the enemy.

In May, the President traveled to the front lines of McClellan’s Peninsular campaign to see the work first hand. Upon arrival, Lincoln discovered that although the Union occupied Fort Monroe, the General had done nothing to silence the Confederate ironclad the Merrimac, or its base of operations at Norfolk, both of which resided just across the waters of Hampton Roads. Furious with McClellan’s complacency, the President took it upon himself to capture Norfolk and began “directing the movements” from his mobile White House at Fort Monroe. [11]

Having taken action and tasted the fruits of his decisiveness, Lincoln thereafter began issuing “explicit and direct command to his generals” through the telegraph network. [12]His deepening involvement with the intricacies of the war led Lincoln to practically live in the telegraph office, going so far as to request a cot be set up in that room so that he could remain in proximity to the wires rather than return to the White House. [13]The cipher and telegraph officers of the War Department on whom Lincoln relied said of the President that the “Commander-in-Chief…possessed an almost intuitive perception of the practical requirements of that….office, and…was performing the duties of that position in the most intelligent and effective manner.” [14]All of the “intuitive perception” in the world would have been useless however, had it not been for the amazing power of the telegraph.

Union Military Commanders Use the Telegraph

Lincoln was not the only Union commander who learned to use the telegraph to project himself across the vast lengths of the battlefront. It was in fact the “Young Napoleon” George McClellan himself that first grasped the great potential of this new technology. Later, General Ulysses S. Grant would perfect the use of the telegraph giving him a precision of control over the movements and actions of his troops unheard of before in the history of warfare.

McClellan had experience with commanding through the telegraph before he was appointed to lead the Union army. Fresh out of West Point, the Army sent McClellan to Europe as an official observer of the Crimean War. There he witnessed the first application of the telegraph in battle. Following that, he resigned his commission to become a railroad executive, where he became intimately acquainted with the telegraph. Thus, when he rejoined the army at the start of the Civil War, there was perhaps no military commander better suited to make use of this new technology.

Within the first few months of the war, McClellan enlisted the services of a Western Union Executive, Anton Stager, to organize a military field telegraph. It was soon after this that Stager was assigned to oversee the operations of the USMTC. In short order, McClellan, because of the telegraph, was able to exert unprecedented tactical communication with his command which allowed him to rapidly change battle plans. [15]He brought his experience with using the telegraph network with him once he was appointed to lead the Union’s forces. Once in Washington, McClellan’s headquarters were quickly “festooned with wires connecting him to all the fronts and making [him] the hub of military information.” [16]

Unfortunately for the President, all the information in the world could not get McClellan to move. The commander who would most effectively employ the telegraph was Ulysses S. Grant. Greely writes that:

From the opening of Grant’s campaign in the Wilderness to the close of the war, an aggregate of over two hundred miles of wire was put up and taken down from day to day; yet its efficiency as a constant means of communication between the several commands was not interfered with. [17]

The lines of the USMTC bound the corps of the Army of the Potomac together like “a perfect nervous system, and kept the great controlling head in touch with all its parts.” [18]Never after crossing the Rapidan did a single corps lose direct communication with the commanding general.

Grant, more than any commander before him, employed the telegraph for both “grand tactics and for strategy in its broadest sense.” [19]From his headquarters in Virginia, Grant daily issued orders and read reports on the operations of his commanders who were dispersed across the vast battlefront of the Confederacy. With Meade in Virginia, Sherman in Georgia, Sigel in West Virginia, and Butler on the James River, Grant commanded a military force exceed half a million soldiers and conducted operations over eight hundred thousand square miles. [20]In his memoirs, General William Tecumseh Sherman said that, “[t]he value of the telegraph cannot be exaggerated, as illustrated by the perfect accord of action of the armies of Virginia and Georgia.” [21]

Conclusion

The successful application of the telegraph by the Union was the result of the concerted effort of Lincoln, his military commanders, and thousands of skilled USMTC operators. By the end of the Civil War, the USMTC had constructed 15,000 miles of dedicated military telegraph lines. [22]These lines were operated in addition to the thousands of commercial lines which were taken over by the federal government. Together this vast telecommunications network brought the President, the War Department, and the commanding generals “within seconds of each other”, though enemy fortifications or even thousands of miles of wilderness might have intervened. [23]

This intricately organized network allowed Grant to utilize the full potential of the telegraph. Grant more than any other commander besides Lincoln, learned to project himself using this new technology. In this way, Grant was able to strategically maneuver his forces across the battlefields of Virginia, Georgia, West Virginia and elsewhere with rapidity and precision. As Plum writes, the telegraph was of “infinite importance to the Commander, who, from his tent in Virginia, was to move his men upon the great continental chess-board of war understandingly.” [24]Grant acquired a precision and speed with this powerful new technology that allowed him to out maneuver his opponents. He used this power to command his army in ways that were unthinkable to previous generations of military leadership. With a clear picture of the immense theater of war and a powerful means of mobilizing his units Grant was able to cut off reinforcements to General Lee and shorten the conflict. [25]

How important do you think the telegraph was in the Union’s victory in the US Civil War? Let us know below.

Remember, you can read part 1 in the series on the history of the telegraph in the 19th century here and part 2 on the telegraph in the early years of the US Civil War here.

[1]Tom Wheeler, Mr. Lincoln’s T-Mails: How Abraham Lincoln Used the Telegraph to Win the Civil War, (New York, NY: Harper Business, 2007), 65.

[2]Ibid., 1.

[3]Bates, Lincoln in the Telegraph Office: Recollections of the United States Military Telegraph Corps during the Civil War, 38.

[4]Wheeler, Mr. Lincoln’s T-Mails: How Abraham Lincoln Used the Telegraph to Win the Civil War, 10.

[5]Ibid., 40.

[6]Ibid., 42.

[7]The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, ed., Roy Basler, (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1953), vol. IV, 485.

[8]Ibid., 499.

[9]Wheeler, 41.

[10]Ibid., 44.

[11]Bates, 117.

[12]Wheeler., 54

[13]Ibid., 77.

[14]Bates, 122.

[15]Edward Hagerman, The American Civil War and the Origins of Modern Warfare: Ideas, Organization, and Field Command, (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1988), 37.

[16]Wheeler, 40.

[17]Greely, “The Military-Telegraph Service.”

[18]Ibid.

[19]Ibid.

[20]Ibid.

[21]Plum, Vol. II, 140.

[22]Greely.

[23]Ibid.

[24]Plum, Vol. II, 128.

[25]Greely.