I United against the Axis

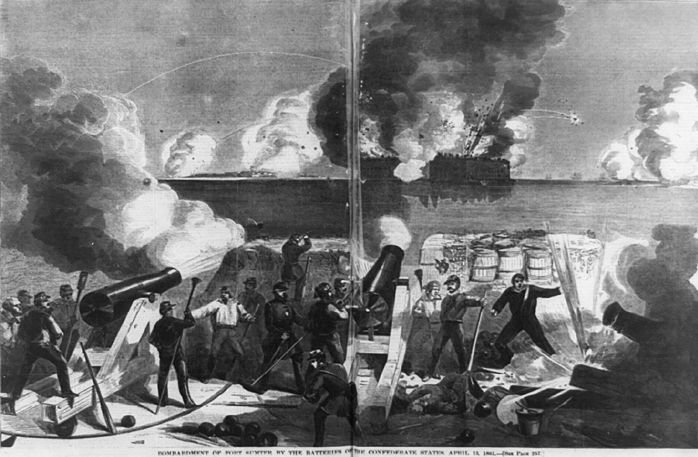

The Italian Invasion of Greece was proven another significant failure for Mussolini. It was repulsed by the Greeks who immediately counterattacked. The Greek army demonstrated extraordinary skills in mountainous warfare and by the end of 1940 thanks to its heroic efforts the Italians were forced to retreat 50 km behind the Albanian borders along the entire length of the front. For several months 16 Greek divisions managed to nail in Albania 27 Italian ones. (Churchill, The Second World War (Vol. I), 2010, pp. 510, 513)

When the Germans came to the rescue at the beginning of April 1941, they offered overwhelming support to the Italians, whereas the British, estimating that the loss of Greece and the Balkans would not constitute a big loss, if Turkey remained neutral, were more reserved. (Churchill, The Second World War (Vol. I), 2010, pp. 544 - 545) Thus, on the 27th of April the axis forces were in Athens. The last stand took place on Crete which was invaded on the 20th of May 1941 by German paratroopers, who, after paying a very heavy death toll, took it by the end of the month. The king and the Greek government together with the British Expeditionary Force and the remnants of the Greek Army fled to Egypt.

II Occupation, resistance and first signs of division

Although their performance at the battlefield was questionable, the Italians were left with the control of most of the Greek territory. A chunk was also reserved for Bulgaria, that finally found exit to the Aegean through Eastern Macedonia and Thrace. The Germans retained Thessaloniki under their control though, together with the most strategically important areas in Central Macedonia, the Greco – Turkish border, several Aegean islands including most of Crete, the port of Piraeus and the capital Athens.

As we have seen, the Italian attack in October 1940 found Greece’s economy in a fragile state with the country relying heavily on imports to cover the needs of its people. (Papageorgiou, History is Now Magazine, 2023) Now the invasion destroyed a significant amount of Greece’s infrastructure and the triple occupation put the external trade to a stop. Soon, especially the urban population, faced food shortages and by the end of 1941 starvation. During the tragic winter of 1941-42 approximately 300,000 people lost their lives. (Tsoucalas, 2020, pp. 89 - 90) Overall, Greece paid one of the heaviest tolls among the allied forces losing 7 – 11 % of its 1939 population during the Second World War. (Wikipedia, 2023)

This situation pushed the Greeks towards struggle rather than passivity. They needed to resist in order to survive. The first resistance group under the name National Liberation Front (in Greek Ethniko Apeleftherotiko Metopo - EAM) was created by the Communist Party in September 1941. Its military branch was the Greek People’s Liberation Army (in Greek Ellinikos Laikos Apeleftherotikos Stratos - ELAS). This was not only the first, but also the biggest resistance group. Indeed, by 1944 ELAS numbered 50,000 fighters in the Athens – Piraeus area only, whereas estimations for EAM members reach up to 2,000,000 (total population 7,000,000). (Tsoucalas, 2020, pp. 91, 99) (Heneage, 2021, p. 188) The most important resistance groups with non-communist leadership were the National Republican Greek League (in Greek Ethnikos Dimokratikos Ellinikos Sindesmos – EDES) and the National and Social Liberation (in Greek Ethniki Ke Kinoniki Apeleftherosi – EKKA). These did not have the size of EAM-ELAS though as the latter dominated most of the country whereas EDES’ bastion was restricted to Epirus and EKKA’s in the mountainous area of Parnassus in Boeotia. (Tsoucalas, 2020, pp. 92 - 93)

For some time , the different resistance groups worked together and with the help of the Allies they managed to carry out formidable operations, like Operation Harling, which destroyed the heavily guarded Gorgopotamos viaduct in Central Greece in November 1942, stemming the flow of supplies through the Balkans to the German Afrika Korps. (Wikipedia, 2023) As a result, 9 divisions of the Axis powers were stuck in Greece to maintain some order, with questionable results, especially away from the main cities and transportation arteries, and that only after intense fighting. As a German report with the title ‘The political situation in Greece. July 1943’ put it:

‘90% of the Greeks today are unanimously aligned against the Axis powers and ready to go into open rebellion’. (Tsoucalas, 2020, pp. 95 - 96)

The pressure the resistance groups exercised on the Axis forces and before that the army’s performance during the Italian invasion in October 1940 showed once again what the Greeks could do when standing united. In the following though, we will describe several open issues tackled by the Greek political establishment of the time in such a way that once again tore the Greeks apart.

As we have seen, before the war Greece was ruled by Metaxas’ dictatorship. (Papageorgiou, History is Now Magazine, 2023) Metaxas died in January 1941, but the government that fled to Egypt together with the king, after Greece’s occupation by the Axis forces, appeared officially as a continuation of this dictatorship. (Tsoucalas, 2020, p. 97) Back home in Greece though, contrary to the anti-Communism sentiments of the government, EAM seemed to have the upper hand and ELAS could field thousands of guerrilla fighters. As the German report of 1943 mentioned above continues:

EAM and its militant organizations have borne the brunt of the resistance against the Axis. Most resistance groups belong to EAM. Politically, it is the leading force and because it is highly active and has a coordinated leadership, it represents the greatest danger to the occupation forces. (Tsoucalas, 2020, p. 96)

But how did the communists gain such an advantage in building the resistance? First, they were already experienced in building illegal networks of operation as they were outlawed by Metaxas’ dictatorship already before the war. (Tsoucalas, 2020, p. 91) Second, the remnants of the Greek Army, whose officers could have been the core of the resistance movement, escaped to Egypt with the king and the government. And it is further suggested that the latter (king and government) did not want to encourage resistance in occupied Greece! (Gerasis, 2013, pp. 90 - 91) We should not forget that Venizelos’ failed coup of 1935 gave the royalists the opportunity to purge the army from elements supporting unreigned democracy and restored the dynasty that was exited in 1924. (Papageorgiou, History is Now Magazine, 2023) Now, the king and the government did not want to risk the return of the democrats under arms within the ranks of a resistance movement that could eventually hinter their return to Greece at the end of the war.

Although the King succumbed to the British pressure and abolished the dictatorship in February 1942 (Tsoucalas, 2020, p. 97), the perceived threat for him and his entourage became more imminent when, in March 1944, EAM formed the Temporary Committee of National Liberation. The latter called for the formation of a government of national unity challenging the legitimacy of the exiled government in Egypt. The call was positively received by a significant amount of the Greek army serving under allied command in Africa. Their demand that the request be accepted by the government in Cairo was vigorously met with the help of the British and 20,000 service men were sent to concentration camps in Libya and Eritrea. (Tsoucalas, 2020, pp. 105 - 110) It is difficult to assume that 50% of the Greek army in the Middle East had suddenly turned communist. It is more likely that these were the democratic elements of the army.

At the same time, back home, in occupied Greece, the situation was also becoming more and more difficult and complicated. Italy had surrendered to the Allies already in September 1943. As the Italians were occupying most of Greece, this created a control gap. To fill this gap, Hitler replaced the Italians with troops transferred from the collapsing eastern front. These men, brutalized by their experiences fighting the Russians, brought with them a different kind of warfare. Fifty Greeks were to die for every German soldier killed, ten for every wounded German, with no distinction made between guilty and innocent. The massacres at Kommeno (Wikipedia, 2022), Kalavryta (Wikipedia, 2023) and Distomo (Wikipedia, 2023) are characteristic of this self-defeating approach, as the Greeks left their burning villages and joined the resistance in the mountains. This together with the weaponry of the 90,000 Italian soldiers that surrendered in Greece in 1943 made ELAS even stronger. (Heneage, 2021, pp. 190 - 191)

To make up for this loss Hitler’s reinforcements from the eastern front were not enough. Thus, the Germans turned for help to the … Greeks! The Security Battalions were set up to act against the resistance and maintain order in 1943 by the quisling government in Athens. Denounced at the time as ‘fascists’ and ‘collaborators’ these people, nevertheless, also included moderates who feared the communists’ post-war intentions and can surely have been no more ideologically attracted to the doctrines of Hitler than most of the ELAS fighters to the doctrines of communism. (Heneage, 2021, p. 194) (Beaton, 2021, p. 437) Indeed, considering that the Communist Party was getting no more than 5-6% of the votes in the national elections before the war (Papageorgiou, History is Now Magazine, 2023), it is natural to assume that most of the rank-and-file EAM-ELAS little knew or care about communism. After all, as we have seen, Greece was a country of smallholders who believed fervently in property ownership (Papageorgiou, History is Now Magazine, 2023) and most of the people who joined EAM-ELAS did it following a message not about class struggle but national liberation. (Heneage, 2021, p. 188) This way the Communists were able to impose their leadership but not their ideology on a significant part of the Greek people. (Tsoucalas, 2020, p. 95)

Thus, all sides were simply fighting to survive in a failed state and to preserve what they could of what they valued, when even the forces of occupation could barely keep order outside the major cities, and only by terrorizing the citizens with arbitrary arrests and mass executions. (Beaton, 2021, p. 437) Towards the end of the occupation then the Greeks had once more started to fight against each other with the resistance groups exchanging accusations for collaboration with the Security Battalions and the Germans. (Tsoucalas, 2020, p. 98) The assassination of EKKA’s leader Psaros by the communists in April 1944 was one of the most striking events of this time and indicative of what was about to follow. (Tsoucalas, 2020, p. 101)

Another part of the puzzle, and a very significant one, was the intentions of the Allies. After all, Greece was a defeated country and its future depended on the overall outcome of the war and the negotiations between the Great Powers of the time. And the decision was that Greece will remain under the sphere of influence of the Western Powers. It was taken during a meeting between Churchill and Stalin in Moscow in October 1944. The exchange of views was done using a rough sheet of paper [there is even talk about a napkin (Heneage, 2021, p. 193)] on which Churchill wrote who would get what. The British prime minister found the whole process, affecting the lives of millions of people, so cynical that he suggested to burn the sheet of paper at the end of the negotiation. But Stalin continued cynically and said: ‘No, you keep it’. (Churchill, The Second Worls War (Vol II), 2010, pp. 1154-1155) It has been suggested that the Soviets informed EAM about their intentions to give up Greece already before Churchill’s visit to Moscow. (Tsoucalas, 2020, pp. 112 - 115)

III Liberation and … another civil war!

Now, with all these in mind, what could have, ideally, be done? The Communists should realize that their military superiority was becoming doubtful, in the long term, without Soviet support and with Greece left under the influence of the Western Allies. After all, most of the ELAS fighters were not actually communists. They should try, nevertheless, to capitalize on the fight they put up against the Axis as leaders of the most massive resistance movement and ‘cash out’, so to say, any positive appeal this might have to the people by getting more votes and seats in the parliament compared to the pre-war period. The king and the government, on the other hand, should play down the communist threat, especially after the decision of the Allies, and work for a smooth transition to the post-war period and for the recovery of Greece that suffered heavy human and material losses during the war. To this end, both parties should lay their guns down, when the Germans fled from Greece in October 1944, and stand united at the peace negotiations claiming effective support for their country.

Ideally yes. But what did really happen? The truth is that at the beginning the Communist Party made some concessions. Instead of using its military superiority to take Athens and the power, after the withdrawal of the Germans, it accepted to participate in a government of national unity under Georgios Papandreou, head of the exiled government in Cairo, and set ELAS under British command. The king’s fate and consequently the form of the state system (reigned or unreigned democracy) would once again be decided by referendum. (Kalyvas, 2020 (3rd Edition), p. 158)

Nevertheless, violent events between the opposing factions did not stop and the mutual suspicion remained obvious. Thus, when the government ordered the dissolution of the guerrilla groups, including ELAS, that were to be replaced by a national army, a crisis erupted. The problem was that the national army was to have the heavily armed Greek brigade, that fought under allied command and the exiled government brought with it, at its core. After the purge of its democratic elements in the Middle East we saw earlier though, this was fanatically pro-royal and the Communists demanded its dissolution as well. Papandreou denied. (Tsoucalas, 2020, p. 117) The Communists then left the government of national unity, withdrew ELAS from British command and organized a general strike and a large rally in Athens. (Kalyvas, 2020 (3rd Edition), p. 159)

The later took place on the 3rd of December 1944 and was drowned in blood when the security forces started firing against the crowd. It is not clear if the order came from the government, the British or if the Security Battalions, whose members at that time were laying low following the developments, were involved in the incident, but hundreds of the demonstrators lost their lives or were wounded. (Tsoucalas, 2020, pp. 120 - 122) In response, the communists chose to resort also to violence and the crisis culminated to the Battle of Athens, that started after the rally and lasted for 33 days. The visit, in the midst of the fighting, of the British prime minister, Winston Churchill, in Athens was indicative of the latter’s determination to keep Greece under the sphere of influence of the western allies. (Churchill, The Second Worls War (Vol II), 2010, pp. 1172 - 1184) His interventions have actually been heavily criticised as triggering the devastating all out civil war that would shatter all hope for post war unity in Greece (Heneage, 2021, p. 197), and it is a fact, that with the help of the British forces that landed in Greece after the withdrawal of the Germans, the government was able to draw the Communists to sign in February 1945 the Agreement of Varkiza. The latter provided for the demobilisation and disarmament of ELAS, general amnesty for ‘political’, but not criminal, offenses, the holding of general elections and the referendum for the fate of the king. (Kalyvas, 2020 (3rd Edition), p. 161)

Nevertheless, as atrocities were carried out by both factions, during all this time, many issues remained open. (Tsoucalas, 2020, p. 133) Things were made worst by the participation in the Battle of Athens of many members of the quisling militias who collaborated with the Germans on the side of the government against the communists. This way, the battle acted as a legitimizer for these organizations, as it seemed to confirm the view that the quisling militias were nothing more than a means of dealing with the communist threat. (Kalyvas, 2020 (3rd Edition), p. 162) With the tolerance of the government these people infiltrated into the ranks of the security forces and continued to terrorize anyone who was or was perceived to be communist. After all, the fact that criminal offences could still be prosecuted even after the compromise reached at Varkiza offered a good pretence. This was also admitted by Nikolaos Plastiras that returned to Greece after 10 years in exile to replace Papandreou in the premiership, before the Varkiza truce. (Tsoucalas, 2020, p. 136) His Venizelist past (Papageorgiou, History is Now Magazine, 2023) was hoped to work conciliatory for the warring factions. (Tsoucalas, 2020, p. 133) To no avail. According to EAM in the year between the Varkiza agreement and the elections set for March 1946 1,289 people were murdered, 6,671 were seriously wounded, 31,632 tortured and 84,931 arrested. (Tsoucalas, 2020, p. 137)

This political climate led the communists and a significant part of other left and centrist parties to abstain from the elections set for the 31st of March 1946. When they realized that this way they would lose any chance they had to co-shape the political establishment after the end of the war, they revised their position, but this was two days after the deadline for submitting nominations. Thus, they asked for the postponement of the elections, but prime minister Sofoulis, leading the fourth government formed after the replacement of Plastiras in April 1945 (Kostis, 2018, p. 296), declined. Ernest Bevin, the British foreign secretary in the Labour government of Clement Attlee, that replaced Churchill in the premiership in July 1945, is supposed to have exercised the influence ensured by the presence of the British army in Greece towards this direction. As a result, voters abstention reached 50%, but the elections gave legitimacy to the right-wing government and cemented the re-emergence of the royalists. Indeed, in the September 1946 referendum on the fate of king George, the system of government was confirmed as a reigned democracy with 68,9% of the votes. (Tsoucalas, 2020, pp. 140-141)

The decision for abstention from the elections of the left and centrist parties and its exploitation from the parties of the right would prove to be a fatal error. The only option left was the extra-parliamentary opposition. Encouraged by the hardening of the Soviets’ attitude already during the Potsdam Conference in the summer of 1945, where they stated their disagreement and protest against the ways of the British in Greece based on Stalin’s ‘old and vague authorization’ to Churchill (see above), and later, in January 1946, during the first session of the UN Security Council, where they demanded the withdrawal of the British forces from Greece, the Communist Party commissioned General Markos Vafiadis to set up the Democratic Army in the mountains in August 1946. (Tsoucalas, 2020, pp. 143-145) Nevertheless, support was to come mainly from the neighbouring Communist countries, Yugoslavia, Bulgaria and Albania, that pledged to fully support the operations of the Democratic Army, during a conference in the Slovenian city of Bled in August 1947. (Kalyvas, 2020 (3rd Edition), p. 163) Thus, in the summer of 1947, Greece was, yet again, engaged in an all-out civil war with incalculable consequences.

IV Fighting among themselves … almost

At the end of the First World War, Greece continued the fighting for another 4 years in an attempt to increase its territorial gains in Asia Minor. The undertaking resulted in the catastrophe of 1922. (Papageorgiou, History is Now Magazine, 2022) At the end of World War Two the modern Greek state had once more territorial gains (its last): the Dodecanese. On the 31st of March 1947, the British surrendered the islands to a Greek military commander although the law on the annexation of the Dodecanese to Greece was published in the Government Gazette on 9.1.1948 with retroactive effect from 28.10.1948. (Divani, 2010, pp. 683-685) Nevertheless, instead of focusing on the rebuilding of the country like most of the winners, and losers, of WWII, the Greeks, once more, continued the fighting. This time it was not about further territorial expansion. It was a fight for power among themselves.

Among themselves? Almost. As I commented before (Papageorgiou, History is Now Magazine, 2023), division invites foreign intervention. Indeed, after the Battle of Athens, Churchill’s remark was that at the time when 3,000,000 men on both sides fight in the western front and massive American forces line up in the Pacific against the Japanese, the Greek crisis might seem of minor importance. But the country is at the nerve center of power, law, and freedom of the Western world. Consequently, he wouldn’t back off easily from the deal he made with Stalin (see above). The problem was that the British Empire was on the retreat after WWII. It was not the British who were to conclude the mission in Greece. It would take the persistent efforts of the one who would soon constitute the united power of the English-speaking world: Uncle Sam. (Churchill, The Second Worls War (Vol II), 2010, p. 1184)

In March 1947 the USA adopted a diplomatic policy, under the ‘Truman Doctrine’, which stipulated that any threat from the Left to a non-communist country would be deterred even by force. The size of military and economic support to Greece thanks to the Truman Doctrine and the Marshall Plan (Wikipedia, 2023) was tremendous. Three hundred million dollars were granted by the US Congress in 1947 only and much more later. The effect of the American support on the army was huge. It reached 200,000 men including well trained mountain troops. It was equipped with modern weapons, artillery and fighting aircraft. A modern communications network was built. The airfields, roads, bridges, and ports that had fallen into disuse during the occupation were repaired. American military advisors were working together with the Greek General Staff for the planning of the operations against the Communists. (Tsoucalas, 2020, pp. 151-152, 157)

The latter on the other hand were in a tough spot. As we have seen they were getting some support from the neighboring communist countries, but only against concessions in Macedonia, which made their cause very unpopular in the rural areas in the north, in view also of recent atrocities of the Bulgarians there during the occupation. (Tsoucalas, 2020, pp. 159-160) Their networks in the cities were also gradually being neutralized by the police as the Communist Party was outlawed and thousands of its members were sent to exile. (Tsoucalas, 2020, p. 158) Additionally, for most of the Greeks 6 years of fighting was already enough. Recovery and financial stability were now the imperative. Any attempt for further unrest met their disapproval and dismay. (Tsoucalas, 2020, p. 148) Thus, the Democratic Army had soon problems in finding new conscripts. Eventually, 25% of the fighters in its ranks were women and the voluntary conscription was replaced by a forced one. (Tsoucalas, 2020, p. 155) This was followed by terror tactics like hostage taking. A striking case was that of young children at the age of 3 to 14 years and their expatriation to Yugoslavia and Bulgaria. (Tsoucalas, 2020, p. 159) All these were exploited of course by the government propaganda.

Things got worse for the Communists because of internal disputes. In view of the problems in conscription, training, and equipment, Vafiadis resorted more to guerilla tactics, but the General Secretary of the Communist Party, Nikos Zachariadis, wanted to turn to more conventional ways of war. (Tsoucalas, 2020, p. 160) Vafiadis was finally replaced by the General Secretary in the leadership of the Democratic Army, but the decisive turn came in June 1948, when Yugoslavia’s leader Tito disagreed with Stalin and his country was expelled from the Cominform. (Wikipedia, 2023) Despite the fact that the Soviet Union offered little practical support during the war, it was the ‘mother’ to which communist hard-liners, and especially Zachariadis, had to obey. (Tsoucalas, 2020, pp. 158-159) Thus, a year later, in July 1949, Tito closed the border and the Democratic Army lost access to the rear of Yugoslavia where it used to withdraw in times of danger in order to regroup and resupply. At the same time, the imminent threat of an invasion of the Greek army in Albania forced the Communist Party to declare a cease fire on the 16th of October 1949. (Kalyvas, 2020 (3rd Edition), p. 166) (Tsoucalas, 2020, p. 162) This is 5 years after the Germans left Athens in 1944.

V The aftermath: A new schism

At the end of the Second World War the magnitude of the disasters that Greece had suffered could only be compared with those of Yugoslavia, Poland, or the Soviet Union. From 1940 till 1944 550,000 people were killed (corresponds to 8% of the total population) and 34 % of the national wealth was lost. 401,500 houses were destroyed and the number of the homeless reached 1,200,000. 1,770 villages were set on fire, whereas the big ports, the railway lines, the locomotives, the telephone network, the civil airports, and the bridges were in ruins. 73% of the capacity of the merchant fleet and 94% of the capacity of the passenger fleet was sunk. 56% of the road network, 65% of privately owned vehicles, 66% of trucks and 80% of the buses was also lost. The number of horses was reduced by 60%, of small animals by 80% and 25% of forests was burned. By 1944 the production of cereals was down by 40%, of tobacco by 89%, and that of currant by 66%. (Tsoucalas, 2020, p. 134)

And yet, in front of all this devastation, the Greeks continued fighting a civil war for another 5 years! This brought more dead (40,000 according to official statistics, 158,000 according to unofficial calculations), hundreds of thousands of additional homeless and material damages comparable to that estimated at the end of 1944. Moreover, 80,000 to 100,000 Greeks branded as communists back home fled or were forcibly taken across the country’s northern border and would have to make new homes in eastern Europe’s communist countries. The largest such Greek community was established in the city of Tashkent in Uzbekistan. (Tsoucalas, 2020, p. 163) (Beaton, 2021, p. 438)

This ‘exodus’ was a manifestation of a new schism in the Greek society that was realized by 1949 and replaced that between Venizelists and anti-Venizelists (and of course others before that): the schism between ‘nationalists’ (ethnikofrones) and ‘communists’. In a nutshell, the nationalists stood on the winning side of the civil war and professed the defence of the ‘Greco-Christian’ tradition against the subversive dispositions of the loosing side, that is the ‘communists’. The distinction was rather blur (e.g. we saw – see above – that many ELAS members were not actually communists) and thus served for the prosecution of many whose political convictions did not suit the state at the time. Indeed, postwar Greece was very far from being a liberal paradise (although neither was it, as we will see, Stalinist Russia). (Heneage, 2021, pp. 205-206) In fact, this schism, in a much milder form though, is carried to this day between the ‘conservative’ or ‘right-wing’ and the ‘progressive’ parties that continue to fail to collaborate even under severe conditions, like the current economic crisis, with devastating consequences for the country.

VI Conclusion: Who’s fault was it?

Greece is probably the only country in the world that does not have a celebration for the victory in the First World War whereas victory in the Second World War is (strangely) celebrated at the date that marked the entrance of the country to the deadliest conflict the world has ever seen and not that of its liberation and exit. The reason, obviously, is the fact that in both cases the Greeks continued the fighting undertaking a disastrous campaign in Asia Minor in the first case and engaging in a protracted civil war in the second. Nothing to celebrate then.

If we were to ask the question who’s fault was it that Greece fought yet another civil war, a popular narrative is that the war was the result of the pressure that the government, supported by the British, exercised on the communists in an attempt to eliminate their influence on the social and political life which was significantly increased as a result of their leading role in the resistance against the axis forces that occupied Greece.

Some of this narrative, implying that the Communist Party was in ‘self-defense’ was carefully presented in the previous sections. And caution is indeed necessary as there is also harsh criticism of the communist leadership’s stance at that time from former party members. There were indeed incomprehensible positions and decisions of the party like (i) the adoption of the slogan for an independent Macedonia and Thrace, particularly unpopular to the Greek general public, (ii) the compromise with the exiled government in Egypt and avoidance of taking the power by force, when ELAS had overwhelming military superiority at the end of the occupation in 1944, followed by (iii) a turn to military means at an unfavorable time, when the government and its army returned and established itself in the country, with the help of the British and later the Americans. These are interpreted as the implementation, by the internationalist leadership of the party, of the decisions and commands of the Soviet Union that were based on the latter’s conflicts, agreements and overall power play with the British and the Americans in the region and elsewhere. (Lazaridis, 2022 (8th Edition), pp. 21-22, 77-82, 84-86 ) In a nutshell, it is suggested that the communist leadership was working for the Soviet interests.

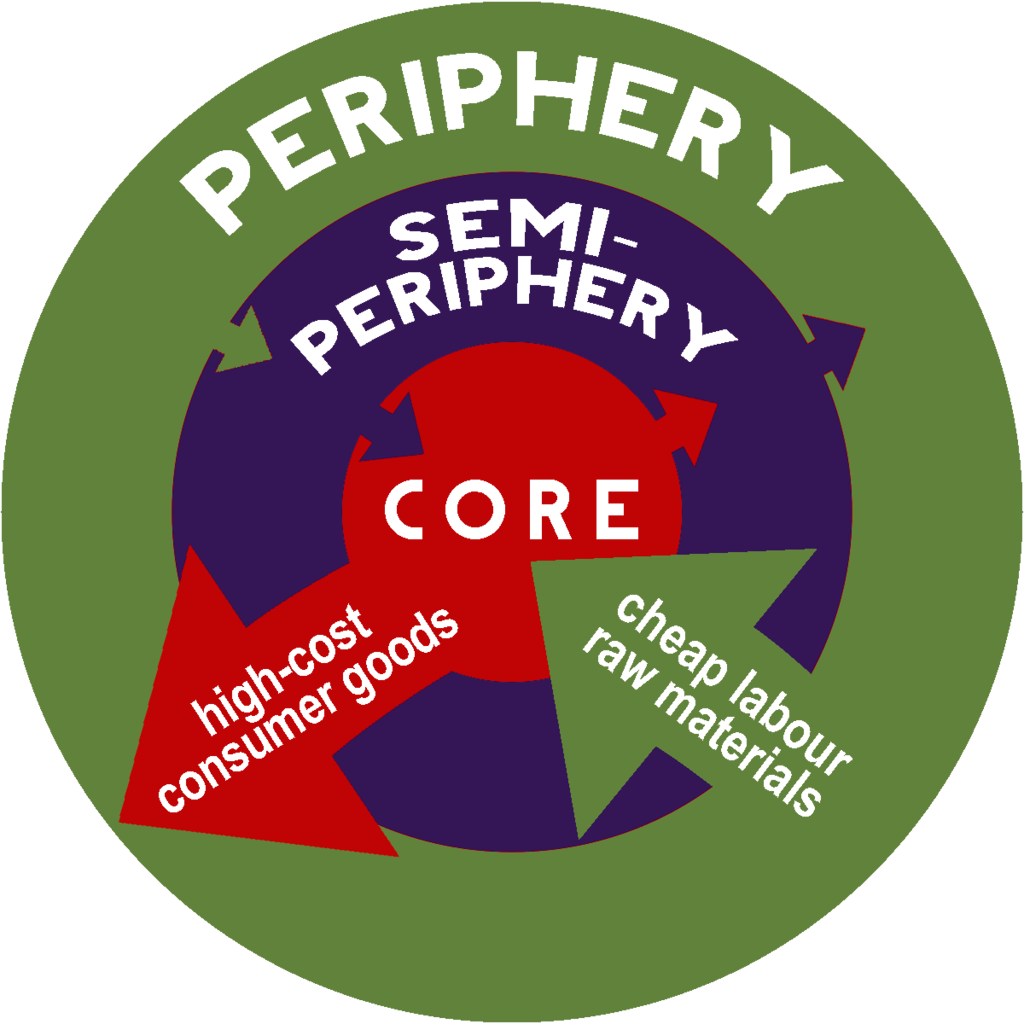

I believe that the developments that culminated to the civil war can be readily understood within the concept of clientelism, which was described in detail in the previous article of this series on the interwar period. (Papageorgiou, History is Now Magazine, 2023) Once again two rival factions used their audiences (clients) to collide for power. Continuing the devastation of the Second World War they worked against the country’s recovery and had to resort to foreign support (intervention) to achieve their goals. The communists lost because they did not get the lavish support that the government enjoyed from the British and the Americans. Additionally, their real audience was much smaller whereas some of their positions made their cause even more unpopular to the public, as unpopular was already the continuation of the war by both factions, after the end of the Second World War. What needs to be stressed here is that clientelism is not something that is restricted internally in a state. When clientelism is in place the state itself becomes a client. The price of American largesse was that Greece effectively became a client state. (Heneage, 2021, p. 204) If the communists had won, Greece would correspondingly become a client state of the Soviets.

In fact, retrospectively thinking, if we were to find a positive element in the events of the period, this is undoubtedly the avoidance of the fate of Greece’s northern neighbors that ended up in the Soviet sphere of influence. On the contrary, Greece remained firmly connected to the West, it managed to benefit from the Marshall Plan and, after the civil war, it followed the amazing economic course of the Western European countries, finally achieving an unprecedented leap in economic development that put it far ahead of its Balkan neighbors. (Kalyvas, 2020 (3rd Edition), p. 170) More on this in the articles to follow.

What do you think of the 1940s in the Modern Greek State? Let us know below.