Museums come in all sorts of shapes and sizes – but what is a museum? Here, Shannon Bent returns and considers the ‘new’ definition of a museum from the body responsible for defining it - and one glaring omission from their definition.

This follows Shannon’s articles on Berlin’s Checkpoint Charlie (here) and Topography of Terror (here), as well as the UK’s Hack Green Secret Nuclear Bunker (here).

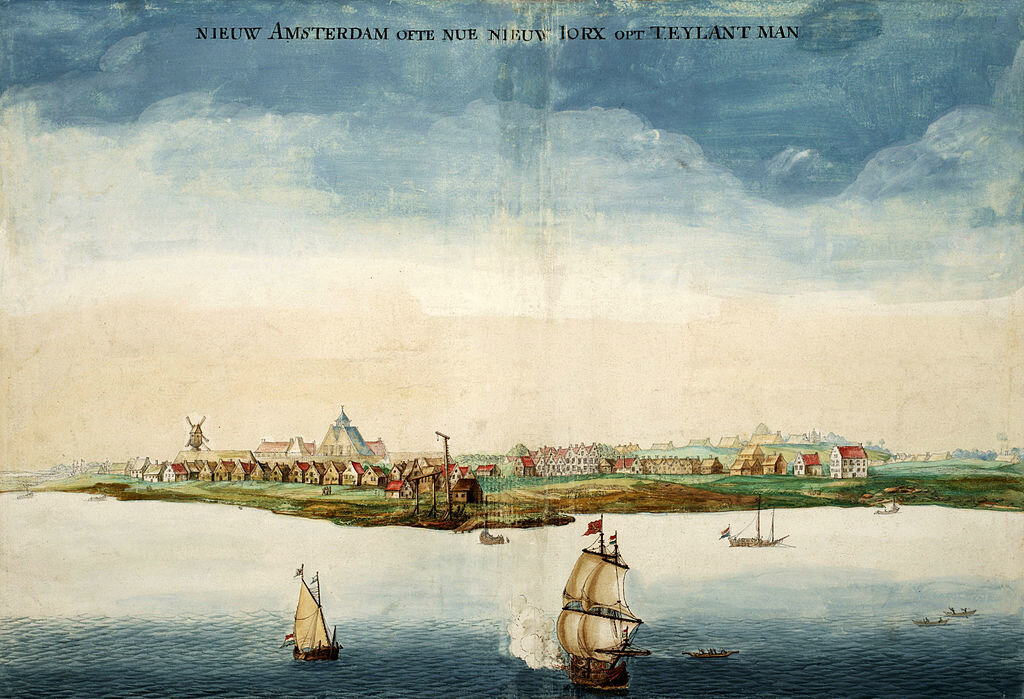

The British Museum, London, under construction in the 1820s.

Museums tend to want to do the same things, generally. They do it in different ways, and provide their information in many different manners, but basically most museums are there for the same reasons. If you asked most people, they would probably say that museums are there to educate, give information, and perhaps even preserve historic objects. This is probably a generally agreed remit, and most people would nod along if you were to say it to them. However, when you break it down there are so many elements to museums. Just from my brief time within museums volunteering and working, I’ve learnt that it simply isn’t just about exhibiting objects and writing interpretation panels on them. There’s the learning department, the archives, the preservation of objects, marketing, retail, catering and many more departments that I couldn’t name off the top of my head. Therefore, any definition of a museum must encompass all of these elements to ensure that each department is clear on what is expected of them.

Of course, there has to be a designated group of people to sort this out and argue about it. It’s like having a board of directors except this is for all museums rather than just one. For this heritage industry, ICOM is this group of people. The International Council of Museums is in charge of overseeing everything to do with museums, holding conferences and workshops all around the world. As a museum you are automatically affiliated with this group, but individuals can join and become members too, for a fee of course. And you have to prove that you are involved in museums in some manner. So really not anyone can join. Anyway, pulling museums together into a common definition is one of their many tasks, and they have recently proposed a new working definition for what museums should be. And it has caused a bit of an argument.

The definition of a museum

There is always going to be someone that isn’t happy with what is said or produced. That’s just the nature of involving so many people, organizations and institutes into one definition. And some of the arguments against this are silly in my opinion. However, I can see where others are coming from. Here’s ICOM’s current proposition:

“Museums are democratising, inclusive and polyphonic spaces for critical dialogue about the pasts and the futures. Acknowledging and addressing the conflicts and challenges of the present, they hold artefacts and specimens in trust for society, safeguard diverse memories for future generations and guarantee equal rights and equal access to heritage for all people.

“Museums are not for profit. They are participatory and transparent, and work in active partnership with and for diverse communities to collect, preserve, research, interpret, exhibit, and enhance understandings of the world, aiming to contribute to human dignity and social justice, global equality and planetary wellbeing.”

Firstly, lets talk about why I like it. Well, from the top, it’s diverse. It directly says it should be ‘democratising, inclusive and polyphonic’, a fancy word for saying including many voices and perspectives. It has many other mentions of diversity too, including ‘safeguard diverse memories’, ‘guarantee equal rights’, and ‘equal access to heritage for all people’. I’m up for anything that actually comments on people from every and all backgrounds actually having access to any heritage they wish to observe and learn about.

The comment ‘work in active partnership with and for diverse communities to collect, preserve, research, and interpret, exhibit and enhance understanding’ is perhaps the moment of gold here. It hits all those points that people traditionally associate with museums that I mentioned at the top of the article, including preservation, exhibiting and researching. ‘Contributing to human dignity and social justice, global equality and planetary wellbeing’ may be very dramatic but it certainly makes the point. It’s nice to see there are other people that believe museums are important to planetary wellbeing… even if it is very theatrical. Perhaps if this perspective is more widely held, all the funding that is being pulled from the heritage sector may slow down and perhaps we can keep these museums and heritage sites afloat. But that’s another argument for another time.

What’s missing?

So far, it doesn’t seem like this missed anything, right? Seems to hit most important points, seems to be fairly inclusive and understanding. Mostly. But here’s the biggest issue. This working definition misses one very important word: education. Yes, that’s right. Not once does that definition talk about education, passing on knowledge and allowing people to learn from the collections of the museums. Whoops. Yes, ‘enhance understanding of the world’ I guess is a broad way of saying educate, but if there is one thing we know about these kind of definitions, it is all about the ‘buzz words’. If you don’t use the actual word ‘educate’, or ‘learning’ then any learning and education departments in museums are going to immediately struggle to justify their requests for funding because it can be argued that museums are not required to educate. This may seem a little far-fetched but in a sector that is rather tight on money as it is, and yes it all comes down to money, I could image any excuse being used to not grant funding. Anyone in this industry has probably seen this happen. Even I have been told within my roles ‘change the wording of that to this. We’re guaranteed more funding if you say it is for this rather than that’. Appalling, I know, but that’s the way the world works unfortunately.

This has been the biggest issue for most people within ICOM and other organizations. It is a vital word, and when I saw the article headline saying that people were arguing about it, I thought it would be over some silly and insignificant word that really didn’t matter. Upon reflection, this is actually rather important and I find myself completely behind the group of people saying the word ‘education’ or ‘learning’ is needed within this new definition. I have recently started a new job within a museum in which I am an ‘Education Facilitator’, essentially delivering education sessions to visiting school groups. When you break it down and look at the different departments of a museum, as I have mentioned before, the education side of a museum, be it visiting schools or the general public, is one of the most important parts. A lot of large museums’ profit comes from their education departments. They need to be able to justify their existence, and show how important and integral they are into the wider machine of their museum.

Conclusion

As yet there has been no suggestions made for changes. I’m sure they will come soon before it is voted on again. I found it very interesting; when I first saw that people were arguing about it, I rolled my eyes and thought ‘leave it alone, it can’t be that bad’. But upon reflection, and now coming from an education department of a museum myself, I can see why this would be a negative game changer for many museums across the globe. I hope this maybe opens peoples’ eyes to the various elements of museums and how just one word can impact this sector. I hope they can come to a new definition, encompassing all the things I love about it, the inclusivity and diversity, while being aware that every single person and department in a museum is a vital part of the overall apparatus that makes this sector as important as it is. We don’t need a definition that I don’t dispute. Let’s just make it the best we can.

How would you define a museum? Let us know below.